Kio

From Circopedia

Magician

By Raffaele De Ritis

From the 1920s to about 2010, three magic acts have been performed under the name "Kio," first by Emil Kio (1894-1965), then by his sons, Igor (1944-2006) and Emil (b.1938). Kio, whether the original Emil Kio or his sons, had an exceptionally brilliant career in the Soviet Union (and later, the Russian Federation) as well as around the world, where they performed extensively on international tours of the "Moscow Circus." Kio’s illusions had a unique particularity: they were created to be performed exclusively in the ring. Together, Emil Kio, Igor Kio and Emil Kio, Jr. have performed for an estimated audience of 180 million worldwide, which arguably makes theirs the most widely seen act in the history of Magic.

Even more than their illustrious father, who was a bona fide star of the Soviet circus, Emil, Jr. and Igor became celebrities in their own right; they appeared on television, either as program hosts or in their own magic shows, and on film, and they were regularly and, sometimes, opulently chronicled in the Russian press—and by the Soviet gossipmongers, who showed a tabloid interest for the peculiar intricacies of their multiple marriages, notably Igor’s matrimonial and extra-marital adventures.

A Dynasty of Circus Magicians

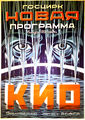

Advertised simply as "KIO," the various Kio magic acts were what the Russians call an attraction(Russian) A circus act that can occupy up to the entire second half of a circus performance., a presentation that can fill up the entire second half of a circus performance. Kio’s original act had been created by magician Emil Hirschfeld-Renard in 1932. After his death in 1965, the act was inherited by Emil's younger son and assistant, Igor (who presented it in his father’s version until 1976, and then completely revamped it), and was reproduced in 1966 as a second Kio unit presented until the early twenty-first century by Igor’s elder brother, Emil, Jr.A true pioneer of circus magic shows, Emil Kio managed to fit large-scale illusions into the challenging environment of the circus ring: A space fully lit, offering a 360º visibility, with an open space above and no back curtain or wings—thus leaving the magician to work surrounded by thousands of eyes, with no easy way to conceal anything. Kio also personalized apparatus-centered illusions dating back to the "Golden Age of Magic" (roughly 1890-1920), which he presented on a spectacular scale. In most instances he had to find new and subtle solutions to create his deceptions in his unusual performing space.

Kio’s magic performances were enhanced by a visually dramatic use of a troupe of up to fifty participants—either performing assistants or participants in the illusions. Kio's act, in its subsequent developments, reached an impressive artistic coherence in the presentation of large-scale illusions; the Kios, father and sons, excelled in staging the flow and pacing of a large number of extras that had to deal with cumbersome and complicated scenic props.

The Kios’ celebrity, which eventually far surpassed the sole fields of magic and circus, propelled them to the heights of Soviet society. However, if the Kio brothers' private lives have been largely exposed to the public, their and their father’s artistic careers have always been shrouded in mystery and misinterpretation. Whenever any of the three illusionists entered in contact with the press or even with local magic communities during their Western tours, they seldom answered questions. Furthermore, the similarity of their shows has contributed to generate a great deal of confusion.

EMIL KIO (1894-1965)

Emil Teodorovich Hirschfeld-Renard (Эмиль Теодорович Гиршфельд-Ренард) was born in Cëcis, in Latvia (then part of the Russian Empire) on April 11, 1894. His parents belonged to the large German-Jewish community of Latvia; his mother came from Kuldīga (Goldingen in German), the capital of the Courland Governorate of the Russian Empire, a city that had an important Jewish population. Emil was the eldest son of Theodor Emilevich Hirschfeld-Renard and Beatrice, née Fukelman, and had two brothers, Felix, an economist who was eventually arrested as a Trotskyist anarchist during Communist purges, and Garry (Harry), who became an aeronautics engineer. (The origins of the French part of the family surname, Renard, remain unknown.)Theodor Hirschfeld, a salesman, eventually settled in pre-revolutionary Moscow. Facing his house (on the animated Sretenka Street) was a small satiric theatre, the Odeon. Its shows were forbidden to minors but, at age sixteen, young Emil began to visit it with his father’s complicity: he hid himself under Theodor’s ample winter coat. The shows at the Odeon consisted notably of satiric sketches and songs poking fun at the actuality, written by popular artists Nikolai Smirnov-Sokolsky (1898-1962, who would become a close friend of Kio's) and Grigory Afonin (who became a silent-movie star).

If not poor, the Hirschfeld family was not wealthy either and, when his father died in 1916, twenty-two-year-old Emil had to find a job. He applied for a position at the Odeon and, since he had become quite familiar with its shows, he was hired to replace one of the company’s actors. One piece consisted of a curtain painted with a human body, with holes in the place of various organs, through which performers showed their heads: Emil made his acting debut playing a liver! He eventually graduated to more substantial parts under the guidance of the Odeon’s owner and director, Nicolai Grinevskiy.

The 1917 October Revolution surprised the Odeon’s company in Kiev (Ukraine was part of the Russian Empire) in the middle of a tour. They immediately tried to organize a safer engagement out of Russia and went to Warsaw, Poland. But their show, written for Russian audiences, was out of place and suddenly outdated, and poor business forced the company to dissolve. Emil found a job in the traveling circus of Alksandr (Alessandro) Ciniselli (1861-1933), former director of the Circus of Warsaw and son of Andrea Ciniselli (1840-1891) of the famous Italo-Russian circus dynasty.

Apprenticeship (1917-1921)

Emil worked with Ciniselli as a stable boy, cashier, accountant—in short making himself "generally useful" as the circus saying goes, and acquiring a full circus education. Unlike his forebears’ enterprises, Alessandro Ciniselli’s traveling circus was a modest affair where multitasking was a rule. He had two partners, the Russian clown Ivan Radunskiy (1872-1955) and Radunskiy's partner at the time, the Pole Mechislav Stanevsky (1879-1927), who formed then the legendary clown duo Bim-Bom. Since the show needed all the help it could muster, Stanevsky created a basic Washington trapeze(orig.: "trapèze à la Washington" – French) A heavy trapeze with a flat bar, on which an aerialist performs balancing tricks. Originated by the American aerialist H. R. Keyes Washington (1838-1882). act for Emil.

A fakir was part of the show, performing under the rather generic name of Ben Ali. He became Emil's friend, and encouraged him to work occasionally in his place. Until then, Emil had never shown any interest in magic: As a child, he recalled having seen a magician named "Bosco II" which he found boring. However, Emil’s talent as a fakir were limited and, necessity obliges, he enhanced his act with a few run-of-the-mill magic tricks. It showed some promise, though, and at Ben Ali's and Stanevsky's suggestion, he went to Berlin to purchase new props at Conradi’s, one of Europe’s premier magic shops, which was run by Friedrich W. Conrad, a.k.a. Conradi, a magician, magic dealer, magic teacher and publisher of the magazine “Der Zauberspiegel” (“The Magic Mirror”).Emil bought a classic “sword box,” the presentation of which Conradi himself taught him. Back in Poland, Emil staged it with a rejuvenation theme: An old lady in black dress entered the box and reappeared transformed into a young lady in white dress, with feathered hat, umbrella and a dog. To play the lady, he engaged the services of Klotilda "Tilly" Ciniselli, one of Alessandro’s three daughters. It was a modest creative achievement, but original enough for a small circus, and a harbinger of things to come: Emil's long career would be punctuated by countless thematic and surprising variations on otherwise standard box illusions.

It is possible that magic was a way for Emil to satisfy his passion for performing in the only circus area that, at a basic level at least, didn't required much more skills than good acting and correct prop handling. So, around 1919-1920, he began honing a true magic act. However, he was soon facing two issues: The need of a proper stage name (a Jewish name was not always welcome, so Hirschfeld was not a good option) and language limitations (his Polish was far from fluent). Thus, he chose a new stage name, Kio, and stuck to illusions that didn’t require spoken explanations.

The origins of his stage name are not clear. In his memoirs (published in 1958), Kio said the name came from seeing a neon sign on a movie theater, a kino in Russian, the "n" of which didn’t lit: It read KIO; Stanevsky's wife suggested that it would make a good stage name. Later, Igor Kio dismissed his father's story, telling that it came from a Hebrew invocation, "'tkio... 'tkio...," which Emil heard repeatedly coming from a synagogue where he had found lodgings. The invocation in question is hard to trace but, if true, anti-Semitic sentiments in Soviet Union may explain why Emil didn’t relate this story.

Yet, we may also consider the fact that, at the time, Europe's most famous oriental-style magician was Okito (Thomas Bamberg), a Dutch magician in spite of his oriental name, who had visited Russia and Poland. Kio’s original stage costume had an "oriental" style, with turban and kaftan&mash;a trend at that time, especially popular in the rural areas of central Europe, where it suggested mystic powers to often poorly-educated audiences. Whatever the true origin of his stage name, Emil would later make it his and his sons’ legal name—although if he dropped Hirschfeld, he kept Renard: The family's legal name became Renard-Kio.

Finally, in 1921, the Bolshevik revolution was over and the situation in the new Soviet Union was gradually returning to some form of normalcy. Replete with a brand-new "oriental" magic act and an exotic name, Emil Kio returned to Russia.

The NEP Years (1921-1932)

In the new Russia, which will become the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics in 1922, the NEP (New Economic Policy) plan aimed at organizing and overseeing all public activities. It encouraged leisure time and amusement for workers, which led to the re-organization of the performing arts. Therefore, even small-time acts like Kio’s were able to find work through a new organization, GOMETs (State Organization for Music, Variety and Circus)—the forerunner of SoyuzGosTsirk—which sent them perform in factories and workers’ recreational spaces. Kio soon got booked on the summer-stage circuit in city parks, an old urban tradition inherited from the Imperial era. Billing himself as Kio — The European Magician, Emil spent his early performing years in Moscow's park theatres and touring minor theatres or public spaces in the provinces.

In 1923 he was in Petrograd (the old St. Petersburg soon the be renamed Leningrad) at the People's House theatre. There, he was noticed by local GOMETs officials, who sent him to the brand-new "Film + Estrade" state circuit—a formula designed to fill movie theaters by presenting variety (estrada in Russian) acts in addition to films. After visiting GOMETs’s central office every morning to get his next assignment, Emil spent his free time with a carpenter, building new illusions.Soon, a staple of Houdini’s show (who had performed with great success in Russia), the Metamorphosis Trunk, was added to Kio’s repertoire, as well as the Ethereal Suspension, the levitation of a girl, replete with an "hypnotic" presentation fitting Kio’s oriental character. The Kios, father and sons, would keep these two pieces in their rotating repertoire until the very end, with countless improvements added over the years.

By 1925, Kio had already a sizeable company of ten assistants, onstage and backstage, to which he would soon add a group of midget performers—following in that the example of the famous Italian magician Chefalo (Angelo Raffaele Cefalo). Kio’s repertoire relied mainly on magic apparatus, big and small, with occasional forays in hypnosis and mind-reading to emphasize the "oriental mystery" of his presentation. However, his "mystic" approach was much less successful with urban audiences than it was with their rural counterparts. A discrepancy that Kio discovered at his own expense in 1932, when he got his first big break with an engagement at Leningrad's Tauride Garden theatre (in the gardens of the Tauride Palace), in the historic heart of the city.

After years of toiling in small-time venues, Kio had finally received help from GOMETs to improve his presentation with fresh scenery and new illusions. However, his style had remained provincial, and a Leningrad newspaper had titled its review of Kio’s act, "A mountebank on Nevsky"—not a compliment in Russia! Leningrad’s audiences were, then as now (and indeed, before then) quite refined and discerning, and the change of regime had not altered their well-ingrained tastes. Yet, Kio’s discomfiture illustrated a latent problem in the emerging Soviet Union: The poor quality of many of its indigenous performers.

With the single exception of the Nikitin brothers, circus and variety in old Russia had been in the hands of entrepreneurs of foreign origins (the likes of Cinisellis, Truzzis and Salamonsky) and the same applied to most of their star performers. Unfortunately, the Bolshevik Revolution had forced many of them to leave the country (as indeed Kio himself had done). Although GOMETs still resorted to hiring foreign talent, this situation was deemed unacceptable by the Soviet powers, which would eventually lead to the creation, in 1929, of the State College for Circus and Variety Arts (better known as the "Moscow Circus School")—the remarkable achievements of which would emerge much later.

Kio's Circus Attraction (1932-1945)

By the mid-1930s, Soviet artistic activities were on their way to full nationalization. The first State Circus production had been staged in 1920 in Moscow, and the first state-operated new circus buildings began to pop up in the provinces around 1925. A well-structured management of the national circus system, GosTsirk (State Circus), was finally established in 1936. Meanwhile, an intense production activity had started to materialize: Directors, writers and choreographers were asked to improve and structure the work of some promising Russian circus and variety talents. Kio was one of them.

With the help of director Boris Shakhet (1899-1950), GOMETs had already begun to invest in Kio's rich and luxuriant oriental imagery; it had even issued a personalized poster heralding "Kio and his 75 assistants — including midgets." At that time, his stage act included about ten to fifteen standard illusions, including a lady sawed in two, a classic levitation, the Pharaoh's vase (a huge vase filled to the rim with a succession of water buckets, out of which appeared an assistant at the end), and a "torture press" involving a showgirl and a few midgets.In 1932, Kio was noticed by Aleksandr Dankman (1888-1951), GOMETs’s artistic manager, who envisioned for him a career in the circus. Although he was indeed happy that his artistic potential had been appreciated, Kio was not sure he could accept the proposition. In spite of his early beginnings in a circus ring in Warsaw more than a decade earlier, he was now used to working in frontal stage magic and, more importantly, he needed a flat and equalized floor to roll his large props in and out, which was near impossible on a traditional circus ring, even covered with a carpet.

GOMETs tried to solve the problem by building a full stage over the ring; a solution that proved unpractical. They eventually resorted to building an ornate circular floor that fully covered the ring, whose elements were put together during intermission—a system that had already appeared in European circuses. Kio’s floor system was sturdier, though, and it will be used by the Kios until the end, especially since it would turn out to be quite useful for surprising deceptions. Emil Kio finally accepted Dankman’s offer; he would henceforth spend the rest of his long career in the circus ring.

Thus, Kio began to create new large-scale illusions that could be presented in the round. He would principally use countless variations of one of the few illusions that could be safely performed with a surrounding audience, the Magic House—a classic illusion created by British magician Fred Culpitt as The Doll House—whose principle allows the appearence, disappearance and transformation of performers. Kio developed various versions of it: The Empty Pier Lighthouse, for instance, which magically turned into a crowded cottage, or Gulliver's Dream, which gave an opportunity to show a castle inhabited by an army of midgets. The midgets were also used in The Chess Game, appearing dressed as chess pieces from eight apparently empty cubes.

Like everything else in the Soviet system, the circus was not just mere entertainment; it could bear complex layers of metaphors and messages and, to this effect, two talking figures were used as direct conveyors of cultural imagery and propaganda: The clown and the magician. Kio had already done satirical magic sketches in his early theater years; in the mid-twenties (still in his fakir period), he had devised an anti-religious magic piece to mock a bleeding-icon miracle. Another sketch, in 1929, had for object the menace of a Chinese invasion, with yet another version of the Magic House that had become a border post hiding saboteurs.

In 1939, for the 20th anniversary of Soviet circus, Emil Kio was one of the few circus artists made Honored Artist of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic. Consequently, Kio began to be featured regularly at the "Old Circus" on Tsvetnoy Boulevard, Moscow’s flagship circus building, and was becoming in the process a popular circus figure. In 1941, the Soviet Union entered World War II and circus propaganda intensified, switching to anti-Nazi material. In one of Kio's crudest sketches, Fritz Goes to War, a German soldier was transformed into his own grave, with a live dog urinating on it. Emil and his company were also sent to perform in military hospitals, and wherever there was a need to uplift the morale of the Soviet population.

At the end of 1941, the Wehrmacht was dangerously close to Moscow and, fearing a German invasion, Kio’s company retreated to safer grounds and performed in the circuses of Gorky (today’s Nizhny-Novgorod) and Sverdlovsk (Yekaterinburg). In 1944, as the war was reaching its conclusion, Kio went to perform in the circus building of the newly-liberated city of Kiev, where he obtained a considerable success; then, in 1945, he celebrated the end of the war with a festive magic production, Karnaval, which he presented at the circus of Ivanovo.

White Ties, Black Tails and Politics (1945-1950)

With the outbreak of World War II, the influx of foreign performers had come to a halt. They were substituted with already established Soviet performers (such as Kio and members of old Russian circus dynasties) and the steadily increasing number of graduates of the State College for Circus and Variety Arts. Hence, a genuine Soviet Circus was born, with its own specific style, aesthetics and, as always in the Soviet Union, its own tenets and principles. From then on, the Soviet Union would develop a purely indigenous circus. This had an immediate impact on Kio’s act.

If the proximity of the audience in the circus had helped Kio improve his connection and interaction with them, it also caused a few problems. The luxurious oriental robes, which may have worked on a distant stage decorated within an "oriental" setting, were deemed offensive to the proletarian crowds who closely surrounded the ring. The new Soviet circus culture tended to reject the balaganshchik (fairground showman) tradition of colorful and somewhat gaudy costumes and imagery. For displaying his opulent oriental imagery, Kio was accused of promoting the bourgeois culture of luxury—that is, a culture of waste. Furthermore, the army of assistants under his control evoked the "imperialistic" master-servant relationship…

This dilemma was one of the great contradictions of the early Soviet Circus: Opulence was amoral and thus to be avoided, but in turn, this principle deprived the audience of the visual aesthetic appeal specific to circus performances. Even clowns and acrobats abandoned sequins and ornate costumes in favor of an extreme "proletarian" sobriety. It had, however, unexpected effects: Presentations supposed to criticize the western culture became a way to justify the use of western aesthetics and music.In 1947, GosTsirk decided to turn Kio’s act into a satirical revue. With the growing post-World War II tensions between the Soviet Union and the West, the idea to make fun of western capitalism was indeed a perfect excuse to justify the use of its aesthetics: jazz, nightclub elegance, showgirls in attractive (and scant) costumes, all mixed in a vaguely art-déco visual concept. Bolshoi Theatre’s Vadim Ryindin, one of Russia’s greatest set designers, conceived for the act a seamless visual image that included floor, ring curb(American. French: Banquette. Russian: Barrier) The circular barrier that defines the ring, and separates it from the audience., props and even the curtain at the ring entrance.

As for Kio himself, he abandoned forever his old oriental image in favor of white tie and black tails, and a more tongue-in-cheek approach to magic. His magic repertoire still used the same classics, but Orientalism had made way for political themes. According to Soviet philosophy, circus could help educate ill-informed audiences through visual propaganda and should be used for such purpose. Using as always ingenuous elaborations on box illusions and Magic House variations, Kio payed his dues.

In The Little House Outside Paris, Kio commented on the debate on the United Nations at the World Congress of Peace (a Soviet-sponsored international organization): An apparently empty custom post eventually revealed a large group of soldiers. Another illusion, titled Mr. Wall Street, criticized the American aid to Middle East: A dozen gangsters emerged from a previously empty "Peace" gift box ostentatiously marked "Made in USA," In A Cultural Head, a giant head was filled with "symbols of Western civilization": A cowboy, comic strip characters, pin-ups, etc., until it was eventually shown to be empty. And on and on…

A Magic Clockwork (1950-1955)

In the fifties, instead of chastising the West, circus propaganda began to focus on celebrating Soviet achievements: Acrobats incarnated the People’s strength and bravery; animal trainers the triumph of man over nature; aerialists celebrated space conquests; Cosack riders and tumblers highlighted the various ethnic traditions of the Soviet Union; and the clown personified the victorious struggles of everyday man. As a magician, Kio revamped himself into a subtly ironical and enigmatic tuxedoed character.

Officially, magic was now seen as a triumph of ingenuity and rationality that stimulated the audience’s intelligence; Russian circus historian Yuriy Dmitriev wrote, "Kio seemed to tell his audience, 'dear friend, I'm here with a series of spectacular puzzles: it's up to you to find a solution, but nothing here is an impossible mystery.'" If in modern magic, the aesthetic debate is between simple puzzle vs. sophisticated theatrical mystery, Kio seemed to achieve an acceptable balance between the two—an approach that was not different, in fact, from that of his contemporary Western colleagues.In 1946, GosTsirk introduced the Central Studio for Circus Arts, a facility with no equivalent in the world, created for the concept and development of new acts in a collaborative spirit. The Soviet State Circus was becoming the Russian version of the Hollywood studio system: Ample time and support for design and planning with the help of directors and writers, engineers and specialized shops to build the necessary equipment, process management and creative pre-production—a way to rethink the creative process in circus arts that would later be acknowledged as having influenced the working methods of Cirque du Soleil and similar organizations.

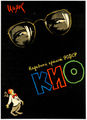

Thanks to the Studio, Kio's was probably the first modern magic production that benefitted from a comprehensive creative team: directors, choreographers, composers, designers, technicians. Much of Kio's new act concept must be credited to the prolific circus director Arnold Arnold (Arnold Grigorevich Baskiy), one of the creative pioneers of the Soviet circus style. Arnold gave Emil a more natural attitude and helped him develop his bespectacled, tuxedoed stage character, which looked like a mixture of KGB agent and sardonic scientist. Another director, Mark Mestechkin, also had an influence on Kio’s presentations.

Kio's act was developed in the early fifties into a full-fledged attraction(Russian) A circus act that can occupy up to the entire second half of a circus performance.—a whole production that practically filled the entire second part of the circus performance. An army of assistants in immaculate uniforms, a plethora of extras, showgirls, midgets and clowns were choreographed in what would become Kio's performance’s unique identity: For forty-five minutes, a whirlwind succession of people, props and boxes moved around the circus ring, in full light and visibility, in a clockwork precision that was entirely cued to the music of a live orchestra. Kio’s attraction(Russian) A circus act that can occupy up to the entire second half of a circus performance. had one of the most perfect timings ever achieved by a full-scale magic act.

Contrasting the frantic activity around him, Kio distinguished himself by his sobriety and economy of movement. Far from the old-fashioned, classic magician style, he remained almost motionless, displaying a relaxed elegance and, yet, appearing firmly in command. Arnold Arnold had pushed for using clowns in and between tricks; Kio worked mostly with Konstantin Berman and Boris Vyatkin, both famous clowns of the Soviet era. A particular innovation was to use Berman instead of a showgirl for the levitation illusion, with the clown unwilling to "fall asleep" under hypnose—yet another demystification of "supernatural" pretense in magic.

Old Classics and Modern Technology

Kio's repertoire, which varied according to his program renewals, included about 350 pieces of magic equipment used at each show. In each of his 45-minute performances, he presented between twenty and twenty-five illusions. Over the years, Kio gradually abandoned basic box tricks in favor of more imaginative illusions, always using the same kind of surprising transpositions he had created for his early satirical pieces.One of his most mystifying illusions was based on an adaptation of an old classic, The Sedan Chair. A horse-driven open cabriolet rode around the ring, with an elegant couple seating on it. The clowns quickly covered the cabriolet with a piece of fabric(See: Tissu) and removed it to to reveal the seats now empty... just as the couple reappeared walking into the ring from the artists' entrance! The illusion was later modernized by replacing the cabriolet by a black ZIL limousine.

A few years later, this illusion evolved into what was perhaps the most sensational of Kio's magic pieces and perhaps his most creative contribution to the art of theatrical magic: His legendary "phone booth" illusion. Two telephone cabins, separated by a distance of about seven meters, stood in the ring. Several characters entered and exited them, disappearing from a booth and reappearing in the other. The pace increased as the illusion went along in a hallucinating choreography, with participants crossing each other in a perpetual motion: the clowns, the couple from the cabriolet, a group of midgets, even Kio himself...

This illusion couldn’t be shown everywhere: It needed a modern circus building or an arena with the necessary technical amenities. In the same period, Kio developed two other signature pieces: The Cremation and the Lady and The Lion. These two magic classics were taken by Kio to a new level of staging perfection, misdirection and suspense. The latter illusion followed by the Cremation became the closing sequence of Kio's attraction(Russian) A circus act that can occupy up to the entire second half of a circus performance., and will be kept, in that position, by his sons in their own shows.

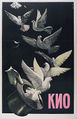

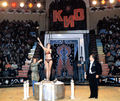

(c.1960)]]The Lady and The Lion illusion saw the transformation of Kio's wife (of whom later) into a roaring king of the jungle; its timing, which took advantage of the clownGeneric term for all clowns and augustes. '''Specific:''' In Europe, the elegant, whiteface character who plays the role of the straight man to the Auguste in a clown team.’s staged incredulity, was particularly interesting. Kio's Cremation, which was easily the biggest version of this illusion ever presented, had its female victim "burning" amidst a real fire with spectacularly high flames and surrounded by an outburst of pyrotechnics; the entire scene was performed to a dramatic musical score especially written for that sequence and played live by the circus orchestra.Kio liked to give small classic illusions a giant makeover. The old "dove pan," for instance—in which the magician produces a couple of live doves from an ordinary empty pan that he had swiftly covered with a lid—was emphasized with giant props and the spectacular flight of several dozens of doves. Kio's team also adapted old technology: a bag escape, with a suspension above the ring, used a small concealed sound system to produce a voice from inside the bag. An interesting trickAny specific exercise in a circus act. was also created with a giant photo camera generating genuine instant oversized photographs of the audience members—a magician's ingenuous creation that had preceded by decades Polaroid technology...

Kio's act benefited from the work of a few key collaborators: I.A. Bruchanov, the illusions’ builder, was behind the main magic concepts and their engineering; Mark Mesteschin was often involved in their staging; Anna Sudakevich (1906-2002)—a former star of the Russian silent screen—was the costume designer that unified in an elegant style Kio’s army of showgirls, assistants and midgets (Sudakevich is also responsible for Oleg Popov’s iconic cap and costume). Among his most precious onstage assistants were Emil's fourth wife, Evgeniya, and Viktor Tikhonov (who would become an immensely talented animal trainer), as well as Emil’s son Igor.

Kio also benefited from the endless resources of GosTsirk. Its agents scouted the land to provide Kio's act with couples of identical twins of the desired age, sex, size or ethnicity, as well as performing midgets. Additionally, the new circuses that were being built in the provinces and Soviet republics were given special amenities that could serve Kio’s illusions. The floor that he used had been also carefully designed and indeed was used actively in a few illusions. Furthermore, Emil’s brother Harry, the aeronautic engineer, helped make some illusions work, and even toured sometimes with the company. (In fact, with appropriate costume and make up Harry was Emil’s split image!)

Beyond The Iron Curtain (1955-60)

By the mid-1950s, GosTsirk oversaw about fifty circus buildings and two dozens of touring shows (under the big topThe circus tent. America: The main tent of a traveling circus, where the show is performed, as opposed to the other tops. (French, Russian: Chapiteau) or on stage), employed more than 5000 performers and technicians, and took care of countless animals—figures that would increase in the following decade. They gave thousands of shows for millions of spectators around the country, with a regular rotation of programs. Kio's company was regularly booked to fill the full second act of those circus programs. The company covered enormous distances by rail, using several railroad cars to transport their equipment, in order to reach even the most remote circus buildings. They also appeared regularly in the Soviet Union’s premier circuses, the Old Circus in Moscow, and Leningrad’s State Circus (the former Circus Ciniselli). For most of his career, Emil Kio gave about 500 performances a year.

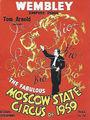

Kio's prestige peaked when, starting in 1956, GosTsirk began to send Soviet circus companies abroad under the generic name of Moscow Circus. Kio participated in many of these hugely profitable tours (for GosTsirk and for the performers, who received a per-diem in precious foreign currency) and became, like Oleg Popov, a goodwill ambassador of the Soviet Union: The symbolic image of his spectacular flight of doves was staged as a metaphoric peace message at the end of his act. (A similar image in Vladimir Grigorevich Durov’s animal act served the same purpose.)In 1958, Kio was awarded the title of People's Artist of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic, with all the related privileges that came with the medal and the title. By then, he had toured in foreign countries behind the Iron Curtain, but not yet in the West. This happened the following year, when the British circus and ice-show impresario Tom Arnold organized with SoyuzGosTsirk (the State Circus Union, which had replaced GosTsirk in 1957) a British tour of the Moscow State Circus, with Kio as its star attraction(Russian) A circus act that can occupy up to the entire second half of a circus performance..

Arnold opened his Moscow State Circus tour on June 10, 1959 at the 12,000-seat Wembley's Empire Olympic Pool (home to his annual ice spectaculars), for a six-week run. The Koch Sisters and their giant semaphore, tight-wire dancer Nina Logacheva, juggler on horseback Nikolai Olkhovikov and other stars of the Soviet circus filled the first half of the show. Kio’s floor was installed during intermission, and the second half was entirely his. Kio's Magic Circus was introduced by a lavish prologue including a European selection of clowns, aerialists, acrobats, plus the "black art" duet, Emerson and Jane.

Then, at last, the Western world discovered Kio’s cornucopia of spectacular illusions, some of which he interchanged during his London engagement. His success was considerable with the press and audiences alike, and the British magic community invited him to the Magic Circle, the world's oldest and most distinguished professional magic institution (founded in 1905), where they presented him with an honorary membership and the "Silver Wand" award.

The following year, in the summer of 1960, Kio became the first Soviet circus artist to appear as a guest in a Western circus production (an extremely rare occurrence indeed). It happened at the Cirkusbygningen, Copenhagen’s historic circus building, where Kio filled the second half of the legendary Cirkus Schumann’s annual summer production—a contract that had been negotiated for them with SoyuzGosTsirk by Tom Arnold. In 1961, Kio was the headliner of the first Moscow Circus troupe visiting Tokyo, and until 1965, he shared his time between performances in the Soviet Union and tours of the Moscow Circus in Hungary, Poland, Syria and Saudi Arabia.

Emil Kio’s Family Life

If Emil Kio showed a quiet, relatively emotionless persona in the ring, his private life was, in contrast, quite eventful. He was officially married four times; his first wife, Olga, whom he married in the twenties, was one of his assistants. His second marriage, with Anfisa Aleksandrovna, a physician, didn’t last long. His third wife, Kosherkhan (Kosha) Borukaeva, was an actress who came from an Ossetian princely family (her father, Tokh Borukaev, had been a victim of Communist purges); Kio met her during a theater engagement in Ossetia and she gave him his first son, Emil Jr., born in 1938. She then went on to work as her husband’s assistant.

Emil Kio’s fourth wife was Evgeniya Smirnova (1920-1989), who was twenty-six years his junior. She was a dancer in his company, whom Emil married after she had given him his second son, Igor, in 1934. She would hold a key position in the act, on- and off-stage, and would be the sole performer of the Lady and The Lion illusion, which was always presented in person by her husband.Evgeniya and Kosha, the mothers of Emil’s sons, both worked in Kio's act and shared his three-room apartment in Moscow. They both enjoyed a life of relative luxury, since Emil had become a prominent and privileged public personality, known for his elegance: His bespoke suits were cut by Nikita Khrushchev’s tailor! His two sons became part of the show quite early, first working among Kio’s company of midgets. Then, by the late 1950s, both had become full-fledged assistants, preparing or repairing props, and gradually taking the spotlight to present some of the illusions.

Then, Emil Jr. left the touring life to pursue engineering studies (perhaps inspired by his uncle Harry, but strongly encouraged by his father), while Igor became his father's principal assistant, more often than not taking his place: By 1959, Emil's health had begun to weaken, so much so that, after 1961, Igor had to take over the attraction(Russian) A circus act that can occupy up to the entire second half of a circus performance. almost completely, sometimes with his brother Emil, Jr.—although their father always kept for himself the presentation of the Lady and The Lion illusion performed by his wife, Evgeniya.

Emil Kio passed away on December 19, 1965 in Kiev, during an engagement there at the State Circus building. His funeral in Moscow was attended by all major players of the Soviet Circus, as well as a host of important personalities from the Soviet government—and everywhere, the international magic community paid tribute to Kio’s remarkable achievements. He was buried at Moscow’s Novodevichy cemetery, the resting place of the Soviet Union’s heroes—that is, the major personalities of politics, sciences and the arts. In 1989, the USSR Postal Service produced a postage stamp honoring the late magician.

IGOR KIO (1934-2006)

Of Emil’s two sons, Igor Kio was the most gifted and certainly the most colorful. He was born Igor Emilevich Hirschfeld-Renard in Moscow on March 13, 1944. His mother was twenty-four-year-old Evgeniya Smirnova (1920-1989), a dancer in Kio’s act, who would become Emil Kio’s fourth wife (they were not yet married at the time of Igor’s birth).As a kid, Igor, who was a football (soccer) fan, begun training, through his father’s connections, with Russian football legend Konstantin Beskov, but his parents didn't want him to leave the circus, and nothing came of it. For a short time, he was also apprentice editor at the State circus magazine Эстрада и Цирк (“Variety and Circus”). Nonetheless, he and his elder brother, Emil, Jr. had participated in their father’s act since a very young age (appearing first among Kio’s group of midgets when they were children), and Igor finally stuck to serving as his father’s principal assistant.

In 1959, After his British tour, Emil Kio’s began to have serious health problems, and Igor had to replace him for the first time. At age seventeen, he brilliantly led the act for a six-week engagement at the Old Circus in Moscow, followed by two weeks at Leningrad’s State Circus. By 1960, Igor had taken the full lead of his father’s attraction(Russian) A circus act that can occupy up to the entire second half of a circus performance., Emil Kio presenting only the Lady and The Lion illusion with Igor’s mother, Evegeniya.

Upon Emil Kio’s death in 1965, SoyuzGosTsirk gave the leadership of Kio’s attraction(Russian) A circus act that can occupy up to the entire second half of a circus performance. to his wife, Evgeniya. Quite naturally, she chose her son to succeed Emil Kio in the ring. Filial nepotism was not the reason for her choice: Igor having practically assumed this position since 1960, he was much more familiar with the act than Emil, Jr., whose engineering studies had kept away from the ring for long periods of time. Thus, Igor, who had also developed a good stage personality, kept Kio’s attraction(Russian) A circus act that can occupy up to the entire second half of a circus performance. alive with, to a large extent, an unchanged repertoire.

Matrimonial Scandals

By then, Igor was already quite a celebrity—but not as much for his talents as an illusionist as for his romantic life. In 1962, he was performing with his father at the State Circus of Sochi. Situated on the Black Sea, Sochi benefits from a subtropical climate that makes it in the summer the equivalent of the French and Italian Rivieras: It was the summer resort of the Sovi-et elite (a status it has kept in the new Russia). There, eighteen-year-old Igor met thirty-three-year-old Galina Brezhneva, daughter of Leonid Brezhnev, then Chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet.

Brezhneva loved circus and circus folks—to the point of having married star acrobat (and future circus director) Evgeniy Milaev. Igor and Galina fell in love, and Galina, ignoring the fact that she already had a husband, went on to marry secretly the young Igor Kio! Yet, nothing was secret in the Soviet Union—especially when anyone related to key members of the Communist Party was concerned—and indeed, Leonid Brezhnev was informed of his daughter's conduct and was not amused. He had the marriage swiftly cancelled by the KGB: It had lasted only nine days!Inevitably, the supposedly secret marriage and its outcome became public knowledge, and, in view of the bride’s identity, caused a national scandal. (It would be later revealed that Galina had also dubious criminal connections and a taste for jewelry theft.) Yet, the adventure established forever Igor's reputation and his lifelong place in the Soviet equivalent of Western tabloids. Igor and Galina’s liaison would continue for a while, however. Then Emil Kio thought it would be better to find a suitable wife for his son and elected Yolanta Olkhovikova (from the famous Russian circus dynasty), who was Igor's age and presented a trained parrots act.

They were married in 1964, and, in 1967, Yolanta presented Igor with a daughter, Viktoriya Igorevna. Igor’s matrimonial adventures didn’t end there, and he was to give yet more fodder to gossipmongers. A few years later, Igor lost his principal assistant, Irina Sergeevna, who had just married the Vladimir Vladimirovich Doveiko a famous teeterboardA seesaw made of wood, or fiberglass poles tied together, which is used to propel acrobats in the air. acrobat who was the son of a circus legend, Vladimir Doveiko, creator of the teeterboardA seesaw made of wood, or fiberglass poles tied together, which is used to propel acrobats in the air. troupe bearing his name. Vladimir Vladimirovich's father had noticed a beautiful young debutante on a movie set and told Igor Kio that she would make a perfect new assistant for him. Igor auditioned her in Sochi, and she was hired (the prospect of traveling the world with the Moscow Circus was indeed a good incentive for any young girl). Her name was Viktoriya, like Igor's daughter.

Then, Viktoriya married the juggler Igor Abert, who was part of Igor Kio's company. (Igor Abert was the legendary juggler Eduard Abert's brother). Soon enough, Igor Kio and Viktoriya began an affair. They eventually had a car accident together, and a distressed Igor realized that he had indeed grown very much attached to Viktoriya. So did Yolanta, who divorced Igor in 1974, and would eventually find a new husband in the person of Igor's brother, Emil, Jr.: This time, the drama stayed in the family—although it didn't go unnoticed!

Finally, in 1977, after she had divorced Abert, twenty-five years old Viktoriya became Igor Kio's third and last wife. Then, Igor had a short-lived but highly publicized affair with Alla Pugachova, a former piano accompanist at Moscow’s Circus and Variety College who had become the Soviet Union’s first and foremost pop singer—a star of first magnitude that was, and would remain, the most beloved singer in the USSR (and later, Russia), and whose every move made the headlines. Igor’s love life was once again in the spotlight. Yet, Viktoriya and Igor reconciled, and they remained together (and apparently faithfully) until Igor's death in 2006.

Igor Kio's International Career

Not only SoyuzGosTsirk had happily supported Igor's takeover of his father's act, it also created in 1966 a second unit of the same attraction(Russian) A circus act that can occupy up to the entire second half of a circus performance. led by Igor's brother, Emil, Jr. The acts were slightly redesigned by Arnold Arnold to fit the personalities of their younger presenters, and the taste of the sixties: faster pacing, original musical scores with swing and jazz echoes—in large part written by the composer Anatoly Kalvarskiy)—and a new set design with neon-lit columns, a new ring floor and refreshed uniforms. A novelty feature was the addition to the act of ten showgirls emerging in the opening sequence from ten empty boxes that had been ever so briefly concealed under a cover flown from the cupola.

After a successful tour of Japan in 1965, and a triumphal engagement at Moscow's "Old Circus", SoyuzGosTsirk decided to send twenty-three-year-old Igor to the United States and Canada, to headline in 1967-68 the second North-American tour of the Moscow State Circus produced by Morris Chalfen. A pioneer of arena entertainment, Chalfen had produced the first "Moscow State Circus" American tour in 1963 in a cultural exchange that included a Russian tour of a Chalfen-produced American Circus, and he had toured his Holiday on Ice ice-show in the Soviet Union. This 1967 exchange also included an American Circus Russian tour. (Chalfen's circus manager was Art Concello).The show opened on October 4, 1967 at Madison Square Garden in New York. It included stalwarts of Moscow Circus tours, such as the juggler on horseback Nikolai Olkhovikov, tight-wire dancer Nina Logacheva and the Doveiko Troupe in its spectacular teeterboardA seesaw made of wood, or fiberglass poles tied together, which is used to propel acrobats in the air. act, as well as the legendary clown (and Russian movie star) Yury Nikulin with his partner, Mikhail Shuydin. Kio's troupe ended the show with a thirty-minute attraction(Russian) A circus act that can occupy up to the entire second half of a circus performance. presented in the challenging expanse of Madison Square Garden. Igor faced the challenge successfully and his introduction to the United States and Canada was a sensation—with the audiences and the press as well as with local magic communities.

In New York, eleven-year-old David Kotkin (the son of Russian immigrants) was deeply impressed by the largest magic production he had ever seen; he will later follow into Kio's footsteps under the stage name of David Copperfield. In Los Angeles, a reception for Igor Kio was organized at the Magic Castle and one of the Moscow Circus performances was filmed by ABC Television for its popular variety show, Hollywood Palace; it was aired on February 1, 1969, showing an excerpt of Kio's act.

Igor and his then-wife Yolanta lived a pleasant life, enjoying the many perks of touring abroad: per-diems in foreign currency (always extremely valuable on the Soviet ruble market), discovery of new worlds, and possibility to acquire goods unavailable in the USSR. They went to Europe in 1969, where they performed at Brussel's Cirque Royal and Paris's Palais des Sports—where Kio's performance profoundly inspired rising magic stars Siegfried & Roy, who were then featured at the legendary Lido of Paris cabaret.

In Brussels, the local press presented him with an "Oscar du Cirque" award. (At the time, the Oscar denomination was not yet trademarked and, in Europe, the word "oscar" had become widely used instead of "award.") Still in 1969, part of Igor Kio's act was filmed by Ilya Gutman for his documentary "Парад-Алле!" ("Parade-Allez!"), a compilation of great Soviet circus acts. The movie was released worldwide in the early 1970s (its English title was Circus Story), which further contributed to popularize Kio's act internationally.

The style and repertoire of Igor's act was regularly refreshed, and he increasingly distanced himself from his father's original style and material. Finally, in 1976, an entirely new act, designed with the help of director O. Levitskiy, made its debut under the title Раз, два, Три ("One, Two, Three"). It downsized a little the plethora of heavy props, assistants and showgirls, and gave the act a somehow more intimate style, better focused on Igor's personality. In 1980, Igor Kio was made People's Artist of the Soviet Republic Federative Socialist of Russia.

New illusions were developed: A tiny glass tank was filled with buckets of water in front of the audience, then was briefly covered to finally reveal a showgirl in place of the water; a grand piano had its legs falling one after another, ending in a state of levitation while Igor was still playing on it. A thrilling variation of the Lady and The Lion illusion was also introduced: The lady entered the cage, and once curtained, the cage with was raised up and, in mid-air above the ring, the curtain fell to reveal the lion that had replaced the lady.

A New Era

In the eighties, while still performing One, Two, Three at home and abroad, Igor began to explore new ways to present his magic act outside the circus. With the advent of Mikhail Gorbachev's Perestroika and the fast disintegration of the Communist regime, the enormous SoyuzGoTsirk organization was in disarray. Soon, the agency, which had been so rich and had brought so much foreign currency into the USSR's coffers, would find itself unable to support its thousands of employees and animals (it would become "an army without soldiers," as Igor noted in his memoirs).

Igor's world was changing. For a Russian celebrity like him, who had been given over the years a practically unlimited budget, it had become very difficult to exploit commercially his artistic product such as it was. His international tours became a thing of the past, and he explored new avenues. In 1985, he created a stage show that he presented at the huge and popular Moscow Estrada Theatre, suggestively titled Without illusions. In 1989, with the increasing privatization of most of the Russian performing arts, he finally left SoyuzGosTsirk to create his own company, Dynasty – Illusion Shows Igor Kio—acquiring most of his magic equipment from SoyuzGosTsirk.Igor now managed his own engagements in circus and variety, as well as acting as an agent for other circus acts. By the late 1980s, gradual privatization became a common practice for the most powerful Russian circus performers, who morphed into talent managers or producers—although their ignorance of business realities often led them to failure. In the early 1990's, as the Soviet Union completely collapsed, Igor produced a huge show at the Kremlin's Congress Hall, and later in sport arenas.

At the same time, he began a successful career as television host for countless shows, series, and variety and circus specials. Starting in 1992, he hosted an annual television special on New Year's Eve, New Year Attractions, which was seen by millions; it was a mixture of circus acts, pop singers and illusions involving celebrity guests. In 1994 he produced and hosted the television special KIO 100 to celebrate his father's centennial, filmed at Moscow's "Old Circus" on Tsvetnoy Boulevard. Along with his brother Emil, he introduced some of Russia's best magicians, actors and singers, and the two brothers performed at the end a spectacular transmutation. They had not performed together in thirty years.

In 2003, Igor Kio finally received the ultimate accolade: He was made Honored Artist of The Russian Federation. Meanwhile, the popular perception of entertainment had changed in Russia, and the 1997 tour of the American magician David Copperfield had more or less relegated Kio's style of illusions into old Soviet folklore. In 1999, Igor had published his memoirs Illusions without illusions, an account of his life that includes his romantic adventures, his relationship with his father and brother, and fascinating stories about Soviet circus history and the personalities of its golden age. A slight unease regarding Copperfield's success can also be perceived in his recollections.

Igor Kio died in Moscow on August 30, 2006, of diabetes complications. He was laid to rest near his father at the Novodevichy Cemetery. Igor had remained faithful to his last wife, Viktoriya, for the last 30 years. The other Viktoriya, Igor's daughter from Yolanta, kept touring along her mother with her uncle Emil's magic show. From her marriage with husband Andrei Novikov, she had two sons, Igor, Jr (b.1986), who became a movie producer, and Nikita (b.1999), who is an actor. The family sold Igor's props to an unknown Russian circus entrepreneur; luckily some of them eventually found their way into David Copperfield's magic museum in Las Vegas.

EMIL KIO, Jr. (1938-)

Emil Emilevich Hirschfeld-Renard was born on July 12, 1938, in Ordzhonikidze (today’s Vladikavkaz) in North Ossetia, Russia, the son of magician Emil Kio and his first wife, Kosherkhan (Kosha) Borukaeva. Even though he spent his childhood touring the country surrounded by magic boxes and trunks (he first appeared in the ring at age two), Emil, Jr. didn't seem initially destined to circus life: His father had decided that one of his two sons should study to make a career outside the circus world.

Thus, in 1960, Emil graduated at Moscow Engineering and Construction Institute. Yet, due to his father's increasingly bad health, Emil, Jr. rejoined the circus to co-lead Kio's magic act and his company with his half-brother, Igor. The day after their father's death in December 1965 in Kiev, he was back in the ring performing three Sunday shows. However, when SoyuzGosTsirk, the State Circus organization, decided to give the responsibility of Kio's act to his widow, Evgeniya, and its presentation to her son Igor, the Ministry of Culture assigned the creation of a second Kio unit to Emil, Jr. The act was re-created from scratch, with newly built props and a new company.For a few years, Igor's and Emil's acts were almost identical (upon SoyuzGosTsirk's request) and, once again, the creative director of the original act, Arnold Arnold, had been involved. Arnold did his best to differentiate Emil's act from Igor's: New floor and set design, new costumes, new musical scores etc. Emil's new "Kio attraction(Russian) A circus act that can occupy up to the entire second half of a circus performance." debuted in 1966. Emil didn't have Igor's natural flair for showmanship, and he turned out to present a much less assuming personality in the ring (one might say that he looked like an engineer doing a casual demonstration of physics).

He was, however, very knowledgeable and precise in building illusions, and he added some creations of his own. His most memorable will eventually be the Indian rope trickAny specific exercise in a circus act.: Emil Kio's remains the sole version of this fabled illusion ever presented in full light and in a circular space. Helped by four showgirls, he inserted a thick rope into a small stand with an opening the diameter of the rope, from where up it went, rigid, in the air; as in the traditional images of the Indian trickAny specific exercise in a circus act., an acrobat climbed the rope up and down, then the rope collapsed and was given to the audience for examination.

Occasionally, the brothers exchanged elements of their repertoire: Igor performed sometimes Emil's trademark Indian rope, while Emil would show Igor's famous dove flight. Following his father's tradition, Emil used clowns in his act, and involved them in the attraction(Russian) A circus act that can occupy up to the entire second half of a circus performance.'s staging and its illusions. In 1971, the contents and presentation of his attraction(Russian) A circus act that can occupy up to the entire second half of a circus performance. were refreshed; Emil Kio became the first magician in Russia to introduce dancing showgirls in his act.

Emil was assisted in the ring by his first wife, Eleanor (Ella) Bolesnanovna Prohnitchi, (b.1937)—a variety performer and the former wife of an actor friend of Emil's—who gave him his first son, Emil, third of the name, born in 1967. (Health issues prevented Emil III from embracing a circus life). Emil's unit became a regular staple of the "Moscow Circus" international tours, and he went to perform in East Germany, The Netherlands, Mexico, Japan, Cuba, France, Sweden, Norway and Western Germany. SoyuzGocTsirk planned his tours and engagements so that they didn't conflict with the schedule of the other Kio, his brother Igor.

Meanwhile, in keeping with the family's tradition of tumultuous private lives, Emil divorced Ella after Lyubov Usasteva (one of a pair of twin sisters performing in his act) had given him a daughter, Julianna, born in 1976. As if that was not enough to entertain the gossipmongers, he re-married the following year with Yolanta, the former wife of his brother Igor. Yolanta became Emil's assistant (a role she knew well from her time with Igor) and was joined in Emil's act by her daughter Victoriya—who was Igor's daughter.

The Last Kio

By the late 1980s, the style of Emil's act changed, as he tried to mix his father's classics with illusions "inspired" by the new American school of illusionism (which would be personified by David Copperfield). In their attempt to be more "modern", Emil's productions of that time lost the aesthetic coherence they had had in the past, and suffered from hesitant pacing, poorly chosen pop music and cheap design. Nevertheless, the attraction(Russian) A circus act that can occupy up to the entire second half of a circus performance. still included more than a dozen of large-scale illusions, and a spectacular opening in which sixteen dancers appeared one by one out of a folding screen that was moved on various spots in the ring—with Kio himself emerging at the end from the midst of the dancers' group.

In 1990, Emil Kio and his company went on tour in the United-States with one of the many short-lived post-communist business ventures, the Great Circus Bim Bom. It had a very strong program with many former Soviet circus stars, but not only "Bim Bom" was a poor choice of a name for an American audience, but also its principal backer, a Saudi businessman, suddenly called it quits, leaving some one hundred artists and a large contingent of animals stranded in Atlanta. The performers remained there for three long months before being able to return home, with the help of such benefactors as Ted Turner and Steve Lieber—then the producer of the very successful "Moscow Circus" tours in America. Emil and Yolanta Kio, who had money of their own, did a little tourism before returning to Moscow.That same year, Emil Kio, Jr. was made People's Artist of the Soviet Republic Federative Socialist of Russia—one of the last circus artists to receive this Soviet distinction. Then, the post-Soviet state circus organization, now renamed RosGosTsirk, developed business partnerships in Japan, especially with theme parks and arena circuits. After a tour there in 1992, and with Russia in the depths of its post-communist collapse, Emil developed his own Japanese unit, spending six months a year in Japan. He even had to build new sets of props to fulfill his many engagements in both Hokkaido and Honshu islands.

After Igor's passing in 2006, Emil remained the only and last Kio in activity. His popularity had remained high (although Emil was never as popular as his brother Igor, the true star of the family); he made regular appearances in the best Russian circuses, wrote articles on magic for children's magazines (two hundred of them just between 1976 and 1994), and hosted television shows. In 1993 he had been named president of the Russian Union of Circus Workers. His magic attraction(Russian) A circus act that can occupy up to the entire second half of a circus performance., even if slightly old-fashioned, still impressed the Parisians in 2001, in one of the very last "Moscow Circus" official tours abroad.

Emil finally retired in Moscow with his wife Yolanta, having given more than 16,000 shows worldwide for a total audience of sixty million. On the evening of September 16, 2019, he did what was probably his last appearance at Circus Nikulin, the "Old Moscow Circus," for the Gala celebrating the 100th anniversary of the Russian State Circus, in front of the circus world's international Gotha. At age eighty-one, he presented a short illusion that made a group of showgirls and a popular singer appear in the ring. It was nearly one-hundred years after the first performance of a Kio in a circus ring.

Suggested Reading

- Emil Kio, Фокусы и Фокусники ("Conjuring and Conjurors") (Moscow, Iskusstvo, 1958)

- Aleksandr Lipovskiy (Editor), The Soviet Circus – A Collection of Articles (Moscow, Progress Publishers, 1967)

- Nikolai Krivenko, Talent, Daring, Beauty – The Soviet Circus (Moscow, Novosti Press Agency, 1959)

- Aleksandr Shneer, R. Slavskiy et al., Маленькая энциклопедия – Цирк ("Little Encyclopedia – Circus") (Moscow, Soviet Encyclopedia, 1979)

- Viktor Marianovskiy, Кио, отец и сыновья ("Kio: father and sons"), (Moscow, Iskusstvo,1984)

- Igor Kio, Иллюзии без иллюзий ("Illusions without illusions") (Moscow, VAGRIUS, 1999) — ISBN 5-264-00141-3

- M.E. Shvidkoy (Editor in Chief) et al., Цирковое Искусство России Енциклопедия ("Encyclopedia of Circus Arts in Russia") (Moscow, Great Russian Encyclopedia, 2000) — ISBN 5-85270-168-8

- Yuriy Dmitriev, Мой старый цирк, бульвар Цветной ("My Old Circus, Tsvetnoy Boulevard") (Moscow, Lazur, 2000) — ISBN 5-85806-028-5

- Yuriy Dmitriev, Знаменитости Российского Цирка ("Celebrities of The Russian Circus") (Moscow, ROSSPEN, 2009) — ISBN 978-5-8243-1163-1

See Also

- Video: Emil Kio, magic act (excerpts), at the Circus on Tsvetnoy Boulevard in Moscow (1951)

- Video: Emil Kio, with Igor and Emil Jr., magic act (excerpts), at the Circus on Tsvetnoy Boulevard in Moscow (1964)

- Video: Emil Kio, Jr., magic act (excerpts), at Leningrad's State Circus (1966)

- Video: Igor Kio, magic act (excerpts), at the Anaheim Convention Center in Los Angeles (1967)

- Video: Igor Kio, magic act (excerpts), in the Soviet documentary Parade-Allez (1969)