Nikolai Pavlenko

From Circopedia

Animal Trainer

By Dominique Jando

Nikolai Pavlenko is arguably the greatest tiger trainer of the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries. His fluid presentation without any of the trappings traditionally used by cat trainers, his focus on featuring the beauty and talent of his animals above the personality of their trainer, the large number of tigers featured in his groups, his remarkable achievements in matters of training, and the sheer artistry of his presentations make him indeed an outstanding circus artist.

Apprenticeship

Nikolai Karpovich Pavlenko was born November 21, 1943 in Severodonetsk, in southwestern Ukraine (then part of the Soviet Union). He began his career with wild animals in 1960, at age seventeen, working as an animal keeper for the Zoo-Circus (Зоо-Цирк), an ensemble of traveling menageries and trained-animal exhibitions created in 1957 by SoyuzGosTsirk, the USSR central circus organization, to visit the cities of the vast Soviet Union that didn’t have a zoo or a permanent circus. Like Pavlenko, many great Russian animal trainers made their apprenticeship in the Zoo-Circus organization.At the Zoo-Circus, Pavlenko worked with a wide variety of animals, including dogs, wolves, brown bears and polar bears, llamas and camels, elephants, and jaguars. He took some time to study at the State College of Zoology, where he graduated as a zoo technician in 1963. He then continued to work for the Zoo-Circus organization, where he moved up to guide and lecturer first, and from 1969 to 1972, to the directorial position.

In 1972, SoyuzGosTsirk sent Pavlenko as an assistant-apprentice to the legendary cat trainer(English/American) An trainer or presenter of wild cats such as tigers, lions, leopards, etc. (and former acrobat) Aleksandrov-Fedotov (Aleksandr Nikolaevich Fedotov, 1901-1973), whose health was failing. Upon Aleksandrov-Fedotov’s death in 1973, Nikolai Pavlenko took over his tiger act. Aleksandr-Fedotov had a very specific style: Donning a beret and an inconspicuous dark outfit with riding boots, he was far away from the "macho" image favored by many cat trainers of the time—an image that still survives today. His attitude in the cage was gentle with little or no use of his whip or other such accessories, letting his cats steal the show.

Tiger Trainer

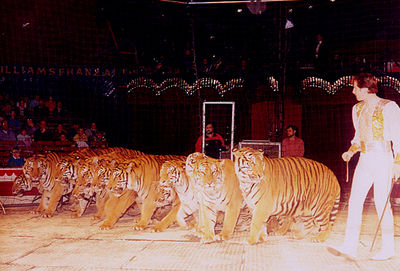

Although perhaps more artistic, Nikolai Pavlenko’s style was indeed influenced by his teacher’s. Pavlenko made his debut with his new tiger act in Lvov, in Ukraine with Aleksandrov-Fedotov’s original group, which included Siberian and Sumatran tigers. In time, Pavlenko went to work exclusively with Sumatran tigers, which are perhaps less spectacular in size than Siberians, but much faster and agile than their Russian counterparts. Pavlenko also began to breed and raise tiger cubs, with a remarkable survival rate close to 100%.In the 1980s, Pavlenko’s tiger group grew in importance, reaching 17 animals by the end of the decade, an amazing number by any standards. More remarkably, all of his pupils effectively worked in the act, most of the exercises being performed by the entire group—while as often as not, in other large cat acts, many animals are just participating in an ensemble sit-up at the top of the act, and spend the rest of it watching the few "star performers" do the tricks (when they are not simply sent out once the opening picture has produced its effect).

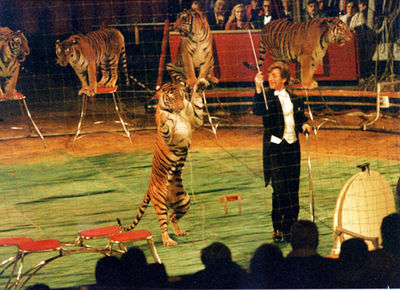

Pavlenko’s style also became very distinctive. His entire act was presented without a whip, or even the long staff used to establish a distance between the cats and their trainer: His only accessory was a short stick that he used like an orchestra conductor’s baton. There wasn’t any "effect" aimed at showing off the trainer’s "courage" or fearlessness: These, Pavlenko considers as an "antediluvian" (his word) style of presentation—like putting one’s head in a lion’s mouth, or feeding a cat from a piece of meat in one’s mouth, the kind of stunts he couldn't even contemplate putting in his act.

The Karajan Of The Big Cage

Pavlenko’s act soon became an attraction(Russian) A circus act that can occupy up to the entire second half of a circus performance. (in the Russian circus, an exceptionally long act that is used as the centerpiece of a show), a fifteen-minute piece presented as a tiger ballet with non-stop action, in which the trainer acted as a ballet-master, or an orchestra conductor. In a country where, since the Durovs, animal trainers have been many and particularly innovative, Nikolai Pavlenko quickly made his mark as one of Russia’s most outstanding cat trainers.

In 1985, Pavlenko participated in the Circuba Festival in Havana, Cuba, where he won the Grand Prize. He then went on tour in Germany with Circus Williams-Althoff in a SoyuzGosTsirk’s Moscow Circus production. It was Nikolai’s first appearance in Western Europe, and the buzz quickly spread among circus aficionados and professionals that an exceptional new tiger act from Russia was in the show. It didn't take long before Nikolai Pavlenko became a name to conjure with in the European circus world.In 1988-89, Pavlenko and his tigers were one of the star acts of the Moscow Circus’s triumphal North American tour—the first after a ten-year hiatus due to the Cold War. After several years touring outside the USSR, Nikolai returned to Moscow, and revamped the presentation of his act. Having always dreamed of working to classical music, he decided to do so with the traditional attire of an orchestra conductor. Evening dress, with white tie and tails, became henceforth his costume in the ring—and Pavlenko’s trademark.

In 1990, he was invited to compete in the 15th International Circus Festival of Monte Carlo: He won the prestigious Gold Clown award, which was presented to him by H.R.H. Prince Rainier of Monaco. Although some ill-intentioned professionals had spread the rumor that Nikolai’s tigers were declawed (which was not true), his appearance at the Monte Carlo Festival was a sensation; a German journalist called him "The Karajan of the Big Cage:" The moniker stuck.

After Monte Carlo, Pavlenko resumed his Moscow Circus engagement with Circus Williams-Althoff. During this German tour, he was featured in a three-part French TV documentary on the circus produced by Dominique Mauclair (the founder of the Festival Mondial du Cirque de Demain), Les Enfants du Voyage, which was broadcast in December 1992. That same year, Nikolai Pavlenko was made National Artist of the Russian Federation.

Down And Up Again

Yet, after the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991, the decade proved very difficult for Nikolai, as it did for most Russian circus artists. The Yeltsin Era, often seen in the West as a time of new freedom and economic liberation, turned in actuality into a disastrous period for the newly born Russian Federation. While the so-called “oligarchs” plundered what was left of the country’s riches, many ordinary Russians found themselves penniless, trying desperately to make ends meet and, quite simply, to survive.

SoyuzGosTsirk, renamed RosGosTsirk, ran out of money. The Durov’s Animal Theater in Moscow, for instance, housed for several years two elephants that belonged to RosGosTsirk; the Theater took care of them since the state company was unable to pay for their upkeep. In such conditions, it was practically impossible for any trainer to ensure independently the upkeep of a large group of wild animals: Nikolai Pavlenko had to part with his tigers, most of which he and his wife, Svetlana, had raised. The great tiger trainer, National Artist of the Russian Federation, resumed his career with a dog act.The twenty-first century eventually brought drastic changes in Russia. The economic situation finally began to improve, and everyday life reverted to some normalcy. Although the well being of the Russian circus was not indeed a priority for the government, the diaspora of circus artists to Europe and North America slowed down, and great new acts were again built at home—albeit certainly not at the same rhythm as in the Soviet Era. Nikolai Pavlenko, for one, decided to rebuild his legendary act with a new group of Sumatran tigers—fourteen in number.

The Karajan of the Big Cage was back—still one of the premier cat trainers of his and any other generation, and artistically, perhaps the greatest. In October 2013, Pavlenko returned triumphantly to Moscow for the Idol circus festival at the Bolshoi Circus, invited, along with the celebrated Italian augusteIn a classic European clown team, the comic, red-nosed character, as opposed to the elegant, whiteface Clown. David Larible, by Askold and Edgar Zapashny as a featured Guest Artist. On that special occasion, The Muscovite audiences were quick to recognize again in Nikolai Pavlenko one of the most remarkable artists of the Russian Circus.

See Also

- Video: Nikolai Pavlenko, tiger act, at the International Circus Festival of Monte Carlo (1990)

- Video: Nikolai Pavlenko's interview for RIA Novosti in Yekaterinburg (2012)

- Video: Nikolai Pavlenko, tiger attraction, at the Bolshoi Circus in Moscow (2013)