The Knie Dynasty

From Circopedia

By Dominique Jando

Knie: The Swiss National Circus

When Friedrich Knie (1784-1850), the son of an Austrian doctor, fell in love with Wilma, a beautiful equestrienneA female equestrian, or horse trainer, horse presenter, or acrobat on horseback., in 1803 at Innsbruck, little did he know that this adventure would be at the origin of one of the world's most prestigious and long-lasting circus dynasties. Born in Erfurt and nineteen years old, the young Friedrich left his studies without a second thought and went on to roam the country with a small company of traveling performers.

Friedrich’s infatuation was short lived, but he enjoyed his new life as an itinerant entertainer, and he decided to create his own company of rope dancers, a craft he had learned during his tours. In 1807, he met and fell in love with Antonia (Toni) Stauffer. Toni’s father, a reputable barber, refused to marry his daughter to a traveling entertainer, and as a precaution, he sent her to a convent. As family lore has it, Friedrich abducted the object of his flame on a night of lightnings and thunder, and the two lovers got married that same year.

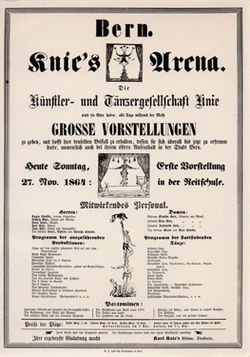

The Knie Arena

Soon came the family’s second generation of performers: Rudolf Knie (1808-1858) was born on July 14, 1808. Four more children followed: Georg (1809-1849), Karl (1813-1860), Fanny-Adelheid (1814-1857), and Franz (1816-1896). All of them would become rope dancers and acrobats.The Napoleonic Wars (1803-1815) had rendered the political and social environment in Austria quite unstable, and the economic situation was uneasy. Yet, the family’s determination helped them overcome the many problems that a traveling company of performers had to face, especially in such difficult times. The Arena Knie was still a small affair that performed outdoors; the high rope was rigged above a stage, on which were presented tight and bouncing ropeAn rope placed between two supports or pedestals, and fastened at one or both ends to a spring or bungee, so that the ropedancer can use the rope as a propelling device. acts, along with an assortment of floor acrobatics and comedy turns. The addition of a few benches around the stage made up the arena.

Friedrich was smart, and one thing became quickly apparent to him: considering the situation, he couldn’t confine his travels to Austria. Germany was added to the route and, as early as 1814, Switzerland. In 1828, the Knies performed in Zurich for the first time, and that same year, in Rapperswil—which was to become much later, in 1907, their hometown. The Knie Arena developed into a successful and reputable enterprise in these three countries.

Rudolf and Franz eventually left the family, and went on to create their own troupe of rope dancers, and when Friedrich died suddenly of a cardiac arrest on February 3, 1850 in Berthoud, Switzerland, Karl took over the management of the Knie Arena. Thirty-seven years old, advertised as "Europe’s premier acrobat," he was particularly brilliant on the high rope, and the star of the family. He was married to Anastasia Staudinger, who had already given him seven children. They represented the third generation of what could be called now the Knie Dynasty—and all of them were already performing: Clara (1832-1916), Sophie (1834-1901), Marie (1836-1890), Ludwig (1842-1909), Nina (1844-1916), Charles (1845-1891), and Antoinette (1846-1923).

Changes of Guard: Karl Knie, Anastasia Knie, and Ludwig Knie

The Knie Arena continued to prosper. It now traveled with twenty persons, and could afford a few hired performers. It gave a varied show, with acrobats and jugglers beside the family’s high and low rope acts, and comedy intermezzi. It was a true variety show, albeit still performed outdoors. In 1859, at Rappersvil, the Knies performed for the Empress Marie-Louise, Duchess of Parma (Napoléon’s widow) and the Count of Montenuevo, the son she had had with her second husband, the Count Albert von Neipperg. At the time, Marie-Louise was staying nearby, in her residence of Meienberg.

In spite of such memorable events, Karl Knie’s career as a director was relatively brief: he died unexpectedly on December 7, 1860, after a last performance at Freiburg-im-Breisgau, Germany, at the age of forty-seven. History doesn’t say if it was an accident or a health problem. In any event, his widow, Anastasia Knie-Staudinger, took over the management of the Arena.Even though they continued to tour Austria and Germany, the Knies had begun to feel at home in Switzerland. In 1866, Ludwig and Charles Knie filed a first application for citizenship in the Canton of Soleure. Apparently, however, an unpaid tax left the request unanswered.

The War of 1870-1871 between France and Germany was another blow to the Knie Arena, which went bankrupt and suspended its activities. In 1872, Anastasia retired to Bern, in Switzerland, where she died nine years later. Meanwhile, it was up to Ludwig and his wife, Marie, born Heim (1858-1936), to revive the Knie Arena. Another period of hard work and financial hardships began.

As soon as they had reached their fourth year, each of their five sons started working in the show: Louis (1880-1949), Friedrich (1884-1941), Rudolf (1885-1933), Karl (1888-1940), and Eugen (1890-1955). Since Ludwig and Marie had wished, without success, to have a daughter, they adopted in 1896 four-year-old Nina Zutter. They also took in a second girl, Anneli Simon, born in 1905, whose mother had neglected her. In turn, both became performers. Then Louis, their oldest son, left the family to create his own company of rope dancers in Germany.

The Swiss National Circus of the Brothers Knie

On December 26, 1900, the Knies finally obtained their Swiss citizenship in the town of Gerlikon, in the Canton of Thurgau. In 1907, they settled in Rapperswil, on the Lake Zurich. Two years later, Ludwig Knie died in the neighboring town of Meilen: He was the first Knie to rest in Rapperswil. His widow, Marie, succeeded him at the helm of the Knie Arena.World War I was another difficult period for the Knies. The Knie Arena had to limit its travels to the Swiss territory, and omit for some years Austria and Germany, which had been on their regular itinerary. But this, if anything, increased their popularity in their country of adoption. Once the war over, the brothers Knie decided to concretize an idea with which they had toyed for a while: They transformed the Knie Arena into a full-fledged tenting circus.

Their mother, Marie, vehemently opposed what she considered a “big folly,” and refused to help them financially. The brothers Knie were faced for the first time with the necessity to break their old principle of never buying anything they couldn’t pay cash: It was on credit that, in 1919, they bought from the tent manufacturer Geiser, in Hasle Rüegsau, a two-pole big topThe circus tent. America: The main tent of a traveling circus, where the show is performed, as opposed to the other tops. (French, Russian: Chapiteau) with a capacity of 2,500 seats. It was set up for the first time on the Schützenmatte, in Bern.

Opening day was June 14, 1919. In front of the big topThe circus tent. America: The main tent of a traveling circus, where the show is performed, as opposed to the other tops. (French, Russian: Chapiteau), the sign on the marquee read, Cirque Variété National Suisse Frères Knie. Sophie Knie-Griesser and Margrit Knie-Luppuner—the young wives of Friedrich and Rudolf respectively, whom they had married simultaneously on March 25—were staffing the box office. The pressure of the crowd was such that the small booths where they sold tickets were smashed, and Sophie and Margrit had to manage a hasty retreat to safety.

But when they left the big topThe circus tent. America: The main tent of a traveling circus, where the show is performed, as opposed to the other tops. (French, Russian: Chapiteau), the public was enthusiastic: They loved the new Circus Knie and, two months only after they had bought their big topThe circus tent. America: The main tent of a traveling circus, where the show is performed, as opposed to the other tops. (French, Russian: Chapiteau), the brothers were able to repay their debt. They were flush again, and that same year, 1919, they built winter quarters in Rapperswil for their circus. Their instinct had proved right, and their new enterprise was already thriving.

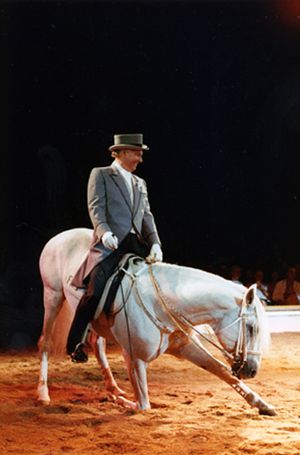

In 1920, for the first time, Friedrich Knie presented Circus Knie’s horses: Now an equestrian and director, he had entered the true aristocracy of the circus. That same year, on May 29, his son, Friedrich, Jr.—the future Fredy Knie, Sr. (1920-2003)—was born in Geneva. Frédy’s brother, Rudolf—later known as Rolf Knie, Sr. (1921-1997)—was born one-and-a-half years later, on November 23, 1921 in Wetzikon.Following the family tradition, Fredy and Rolf made their debut in the ring when they were four years old, as acrobats: They were trained in all fundamental circus disciplines, along with their cousin Eliane (1915-2000)—the daughter of Eugen Knie and his wife, Hélène, née Zeller. But animals were the brothers’ true passion. For his ninth birthday, in 1929, young Frédy was presented with his first horse. He was soon billed as "Europe’s youngest high schoolA display of equestrian dressage by a rider mounting a horse and leading it into classic moves and steps. (From the French: Haute école) rider," and was already on his way to become one of the greatest horse trainers of his generation. Rolf, for his part, would become one of the greatest elephant trainers of his time.

By 1926, Circus Knie traveled with more than eighty wagons for the transport of its equipment, animals, offices, and lodgings. Everything was transported from town to town on a forty-two-car special train. The circus toured extensively in Switzerland, but it visited also Germany and Austria. It gained an excellent reputation in the European circus community and with its audiences, for whom the name Knie had become a symbol of quality.

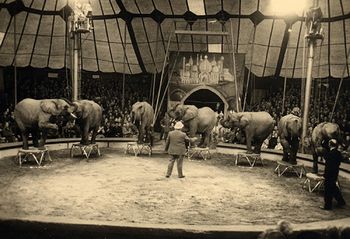

Friedrich, the elder of the four brothers, was first and foremost an artist; his life was entirely devoted to the circus. In the Arena, he had been a strong acrobat and a fine rope dancer and, at Circus Knie, besides presiding over the circus’s equestrian presentations, he sometimes appeared as a white-face clownGeneric term for all clowns and augustes. '''Specific:''' In Europe, the elegant, whiteface character who plays the role of the straight man to the Auguste in a clown team.. Rudolf chose to retire from the ring to prepare the circus's tours and take care of its administration; his brother Eugen, who had been the star of the company in the days of the Arena and had never truly found his place in the circus, worked discretely in the wings, overseeing the technical staff. Karl, on the other hand, was the true showman of the family, a constant dreamer with a soft spot for big spectacle and glitz. In the show, he was in charge of the newly acquired elephants.

The Reign of Karl Knie

Then Rudolf Knie fell ill. After several surgical interventions, he passed away on August 27, 1933—apparently victim of an agonizing colon cancer. He was only forty-eight. Immediately afterward, the ambitious Karl suggested transforming the family enterprise into a public company, in order to increase its capital. Friedrich didn’t like the idea—and neither had Rudolf when he was managing the circus—but Karl was able to convince Eugen: He had thus a majority, and, in 1934, Circus Knie became a limited company, Schweizer National-Circus Gebrüder Knie, A.G. Eighty percent of its shares remained in the family.

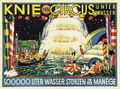

Friedrich had lost. Hurt, he would never come to terms with Karl’s decision to change the company status—and his relations with his brother were severely damaged. They rarely spoke to each other: Their conversations inexorably turned into verbal clashes. Karl, whose vision had prevailed, became in effect the head of the company.Karl could now concretize his artistic ambitions and, that same year, he presented a water pantomimeA circus play, not necessarily mute, with a dramatic story-line (a regular feature in 18th and 19th century circus performances)., Le Cirque sous l’eau, or Der Circus unter Wasser, the complex equipment, set, and costumes of which he had rented from the famous Circus Busch of Nuremberg—the great specialist of itinerant water spectacles. It was a sensation.

The following year, Karl, emboldened by his success, brought fifty performers from India for his own new pantomimeA circus play, not necessarily mute, with a dramatic story-line (a regular feature in 18th and 19th century circus performances)., the aptly named India. It was indeed a very lavish—and expensive—production, but the public didn’t come in numbers large enough to cover the expenses; the season was a financial disaster, and it was up to Friedrich to cover the losses from his own pocket to avoid bankruptcy. This situation, needless to say, didn’t ease his rapport with his brother Karl.

The circus bounced back, but with productions that were better suited to the size of the enterprise. Nonetheless, the Swiss National Circus maintained its reputation of quality, and the programs were always carefully crafted, with some of the best performers of the moment—and excellent animal acts from the rich menagerie the brothers Knie had gathered, especially their equestrian presentations and elephant acts.

On May 26, 1936, Marie Knie-Heim died while the circus played in Zofingue. Then, Friedrich’s health began to decline. In 1937, he had a mild stroke. Soon after, during a performance, a horse pushed him slightly, and Friedrich fell, unable to get back on his feet. To his son Frédy, who had rushed to help his father, Friedrich announced that this was the end of his performing career. Frédy, who was already a remarkable horse trainer, succeeded Friedrich as the Master Equestrian of the circus—and began in earnest a truly outstanding career. The event had another positive outcome: Karl and Friedrich buried the hatchet.

World War II brought its share of drama to Circus Knie, on both business and family fronts. To begin with, the Nazis blacklisted Circus Knie: In 1938, for its production titled Olympiade, the new German flag had not appeared among the other Olympic flags displayed in the show; the Knies had substituted it with a German Navy flag, on which the swastika was hardly visible. Other incidents involving a few Nazi performers led Nazi Germany to ban Circus Knie in all the countries of the Reich.

Once again, the Knies had to limit their tours to Switzerland only. They re-organized their itinerary, and began to crisscross the Swiss Confederation in all its most remote places. This only strengthened their already special bond with the Swiss population, and in that period of scarce entertainment, the annual visit of Circus Knie became an event not to be missed. It would remain so after the war, and never again the Swiss National Circus’s big topThe circus tent. America: The main tent of a traveling circus, where the show is performed, as opposed to the other tops. (French, Russian: Chapiteau) would be set up outside Switzerland.

The Circus of Frédy and Rolf Knie

Then, on July 1, 1940, Karl Knie, who had suffered from bouts of acute depression, committed suicide. Shortly after, in 1941, Friedrich’s health became too fragile for his going on tour with the circus. He passed away on April 27. His sons, Frédy and Rolf, who were in effect already in charge of the circus, took officially the reins at the beginning of the 1942 season: Frédy, who was only twenty-two, as Artistic Director, and Rolf, who was twenty, as Technical Director.Some of the circus's horses were requisitioned by the Swiss Army, but on the brighter side, Frédy and Rolf managed, with the help of the German Ambassador in Bern, to obtain the right to hire performers from countries occupied by the Reich—i.e. most of continental Europe. In exchange, Frédy and Rolf Knie had to perform in Berlin, at the WinterGarten, with their horses and elephants during the winter of 1942-1943: The city was bombed during their engagement, and they were lucky to escape the Reich capital unscathed, with all their animals.

The war over, Circus Knie was in a unique position: A neutral country, Switzerland had maintained a sound economic foundation, and the circus was flourishing. During the war, as soon as it had become possible, the Knies had been able to get the best European artists, who were more than happy to work in a place where they still could make good money and work in a safe environment. The same was true immediately after the war, in a Europe whose economy had collapsed.

Circus Knie’s reputation of quality, which was already well established, grew even bigger under the circumstances, and Frédy and Rolf made sure that it would stay where it had arrived now—at the top! The circus continued to tour exclusively in Switzerland, while some of its animal acts went on engagement during the winter season in major European venues, such as Cirque Medrano in Paris, Circus Carré in Amsterdam, or Bertram Mills Circus in London&mdashoften presented by Frédy and Rolf Knie themselves.

In the fall of 1945, Frédy Knie married Pierrette Dubois. Their first son, Fredy Junior, was born on September 30, 1946 in Bern. Three years later, on August 16, 1949, a second son, Rolf Junior (soon known as Rolfi) was born—also in Bern. The sixth generation had arrived. Then Rolf married Tina di Giovani in 1950; they also had two sons, Louis, born in Bern on June 23, 1951, and Franco, born on September 8, 1954, this time in Rüti.Like the previous generations, young Fredy, Rolf, Louis, and Franco made their debuts in the ring at age four. Frédy Junior rode in high schoolA display of equestrian dressage by a rider mounting a horse and leading it into classic moves and steps. (From the French: Haute école) at Anvers for the first time in 1950. The following year, he went on tour, performing in the show. In 1955, Louis was billed as the world’s youngest elephant trainer. Sadly, that same year, on October 9, Eugen Knie, the last rope dancer of the family and surviving member of the Knie Arena, passed away after a long illness.

In 1956, Circus Knie took residence in its new winter quarters, south of the Rapperswil train station. In 1962, the Knies opened, also in Rapperswil, their very successful Children Zoo, where the animals they didn’t take on tour—and others—are exhibited in the midst of a small amusement park. Meanwhile, in 1959, Eliane Knie, who had performed in the ring for many years with her cousins Frédy and Rolf, had left the circus. (Much later, her grandson, Charles Knie, born in 1947, would create Circus Charles Knie in Germany.)

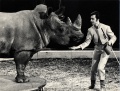

During an engagement with his horses in Berlin in December 1964, Fredy Knie had an appendectomy. On December 27, Fredy Junior took over: It became quickly obvious that he would follow in his father’s footsteps, and was on his way to become one the world’s finest horse trainers. Then at the end of the 1969 season, Rolf Knie, who was perhaps the greatest elephant trainer of his generation, decided to retire from the ring. His son Louis, took over the circus elephants, for which he showed an impressive talent.

The Present Generations

For some years in the 1970s, four generations of the Knie family were living side by side. Frédy had married Mary-José Gaillard in 1972, which brought in the seventh generation with the birth of Géraldine-Katharina Knie on January 19, 1973. At the end of that same year, Louis married Germaine Théron, star of the famous bicycle act, The Theron Family; she gave him a son, Louis Junior, in December 1974.But this multi-generational reunion was short lived: The beloved circus matriarch, Margrit Knie, Rudolf’s widow, passed away in April 1975. A few months later, Rolfi married Erica Brosi, and together they had a son, Gregory, born in 1977. Franco Knie married Doris Agostini, with whom he had two children, Franco junior, born July 10, 1978, and Doris Désirée, born in 1980. With his second wife, Claudine Rey, he has a son, Anthony, born in 1989. Franco married for the third time in 2005; he and his wife, Ckaudia Uez had twins, Nina Maria Dora and Timothy Charles, born September 18, 2009.

In 1983, Rolfi Knie, who had become a very talented augusteIn a classic European clown team, the comic, red-nosed character, as opposed to the elegant, whiteface Clown., left the circus; he first went on to perform his own stage show in various European theaters before embarking on a brilliant career as a graphic artist—his true passion. In 2003, he created a very successful circus/varieté(German, from the French: ''variété'') A German variety show whose acts are mostly circus acts, performed in a cabaret atmosphere. Very popular in Germany before WWII, Varieté shows have experienced a renaissance since the 1980s. seasonal show, Salto Natale, which he managed with his son, Gregory. Then Gregory created his own show, Ohlala—an adult-oriented show that is very successful.

At the end of 1992, Frédy and Rolf Knie retired definitely from the circus business, and left their enterprise in the hands of their sons, Frédy, Louis, and Franco. Following family dissensions, Louis left the circus in 1993, and purchased Elfi Althoff-Jacoby’s Austrian National Circus— which became the Österreichischer National Circus Louis Knie. Then, on August 18, 1997, Rolf Knie passed away after a long illness. One year later, his brother, Frédy, had a stroke that left him partly paralyzed. His second wife, Erica Sigel, took care of him until his death, on December 6, 2003. The circus world had lost two of the greatest circus personalities of the twentieth century.Circus Knie is today one of Europe’s major circuses. For many years, it was traveling on two special trains and several road trucks with an important menagerie. It had also been at the vanguard of animal care, at a time when some circuses still had a hard time adapting to the audience’s change of sensitivity regarding the way animals were kept in traveling circuses—but due to the change of tastes in the early 21st century, the menagerie had slowly been reduced and eventually discarded and the Knies have focused solely on their horses. Yet, the circus is still renowned for its perfect organization, and the high quality of its shows—which have become the standard against which other classical circus shows are measured. Under the management of Frédy and Franco Knie, Circus Knie has maintained its unique position in Europe.

100 Years of Success

In 2019, Circus Knie celebrated its 100th anniversary with an extremely successful tour that had to be extended. At the end of each show, Fredy Knie had announced that he was retiring from the ring (Franco had already retired to take care of their zoo in Rapperswil), passing the torch to the seventh generation: Géraldine Katharina and her husband, Maycol Errani, Franco Junior and his wife, Linna Sun, and Doris. The eighth generation has already arrived: David-Louis, son of Louis Junior and Gipsy Knie-De Rocchi, was born in Austria on August 5, 1999, where he works with his father. Ivan Frédéric Knie, the son of Géraldine-Katharina Knie and Ivan Pellegrini, was born on July 6, 2001. Then Franco Knie Junior, the son of Franco Knie, married Linna Sun, a Chinese acrobat, on May 16, 2003; they have a son, Chris Rui Knie, born on July 22, 2006. Geraldine-Katharina Knie married Maycol Errani in 2009; together, they have two children, Chanel Marie, born March 4, 2011 and Maycol, Jr., born November 3, 2017. Ivan Fédéric, Chris Rui and Chanel Marie are already working in the ring. Finally, Franco Knie Senior and his wife, Claudia, have two children who are in the age range of the eighth genearation: Nina Maria Dora and Timothy Charles.

Suggested Reading

- Alfred A. Häsler, Knie – die Geschichte einer Circus-Dynastie (Bern, Benteli Verlag, 1968)

- Alfred A. Häsler, Knie – Histoire d’une dynastie de cirque (Lausanne, Editions Rencontre, 1968)

- Klaus Zeeb, Pferde dressiert von Fredy Knie (Reinbek, Rowohlt Verlag, 1976) ISBN 3-499-16929-0

- Klaus Zeeb, Les chevaux de Frédy Knie (Lusanne, Editions Payot, 1976) ISBN 2-601-00400-2

- Hans Rathgeb, Von der Arena zum Circus, 175 Jahre Dynastie Knie (Rapperswil, Ra-Verlag, 1978)

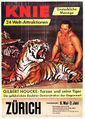

- Louis Knie and Fred Kurt, Elefanten und Tiger im Zirkus Knie (Zürich, Ringier Verlag, 1980)

- Dr. Franz Xaver Erni & Prof. Dr. Ernst M. Lang, Rolf Knie – Elefanten und Artisten (Bern, Benteli Verlag, 1987) ISBN 3-7165-0569-2

- Dr. Franz Xaver Erni & Prof. Dr. Ernst M. Lang, Rolf Knie – Des elephants et des hommes (Bern, Benteli Verlag, 1987)

- Thomas Renggli, 100 Jahre Knie — die Schweizer Zirkusdynastie (Augsburg, Weltbild GmhB & Co, 2019)

- Peter Küchler, Les cent ans du Cirque National Suisse Knie (Rapperswil, Knie Frères, Cirque National Suisse SA, 2019) — ISBN 978-3-85761-327-2

See Also

- Video: Les Frères Knie, documentary (1962)

- Video: Fredy Knie Junior, liberty act, Circus Knie (1973)

- Video: Rolf Knie, Jr., exotic animals, Circus Knie (1973)

- Video: Fredy, Rolf, Franco, Erika, Mary-José Knie, Jrs., high school act, Circus Knie (1973)

- Video: Louis & Franco Knie, elephant act, Circus Knie (1973)

- Video: Louis Knie, elephant and tiger act, at Berlin's Deutschlandhalle (1976)

- Video: Fredy Knie, Sr., liberty act, at the International Circus Festival of Monte Carlo (1977)

- Video: Louis Knie, tiger and elephant act, Monte Carlo Circus Festival (1977)

- Video: Rolf Knie, Gaston Häni & Pipo Sosman, clown entrée, from their stage show (1983)

- Video: Franco Knie, elephant act, at the International Circus Festival of Monte Carlo (2000)

- Video: The set up of Circus Knie in Windisch, Switzerland (2012)

- Video: Ivan Frederick Knie & Worris Errani, double Courier, at the International Circus Festival of Monte Carlo (2020)

- Video: Maycol Errani with Circus Knie's horse carrousel, at the International Circus Festival of Monte Carlo (2020)

- Biography: Louis Knie