Difference between revisions of "The Circuses Of Moscow"

From Circopedia

(→Jacques Tourniaire) |

|||

| (13 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

| − | Although the name ''[[Moscow Circus]]'' is familiar to the public all over the world, there has never been one specific “Moscow Circus” whose troupe toured internationally. The name was a generic term for the circus shows from the USSR traveling abroad during the Soviet Era. It has, over time, become synonymous with “Russian circus.” Yet, there are today ( | + | Although the name ''[[Moscow Circus]]'' is familiar to the public all over the world, there has never been one specific “Moscow Circus” whose troupe toured internationally. The name was a generic term for the circus shows from the USSR traveling abroad during the Soviet Era. It has, over time, become synonymous with “Russian circus.” Yet, there are today (2024) two resident circuses in Moscow, [[Circus Nikulin]] on Tsvetnoy Boulevard, and the [[Bolshoi Circus]] (''bolshoi'' means ''big'', in Russian) on Vernadsky Avenue—and there have been indeed several others before them. |

==Jacques Tourniaire== | ==Jacques Tourniaire== | ||

| − | The first circus built in Russia was established by the French equestrian [[Jacques Tourniaire]], who settled in 1827 in what was then the Russian capital, St. Petersburg. The building, designed by the architect Smaragd Shustov and named ''Cirque Olympique'', was located near the Fontanka canal, practically where St. Petersburg’s [[Circus Ciniselli]] stands today. Tourniaire’s circus had only a short existence: it was bought back by the government of St. Petersburg in 1828 to be transformed into a theater. Still, the event didn’t fail to catch the attention of the Muscovites, who always took exception to the influence of Peter The Great’s Baltic capital. | + | The first circus built in Russia was established by the French equestrian [[Jacques Tourniaire]] (1772-1829), who settled in 1827 in what was then the Russian capital, St. Petersburg. The building, designed by the architect Smaragd Shustov and named ''Cirque Olympique'', was located near the Fontanka canal, practically where St. Petersburg’s [[Circus Ciniselli (St. Petersburg)|Circus Ciniselli]] stands today. Tourniaire’s circus had only a short existence: it was bought back by the government of St. Petersburg in 1828 to be transformed into a theater. Still, the event didn’t fail to catch the attention of the Muscovites, who always took exception to the influence of Peter The Great’s Baltic capital. |

The previous year, Tourniaire had exhibited his equestrian prowess in Moscow, in the manège of the Pashkov mansion (today the Russian State Library), on Mokhovaya Street. Another famous trick rider, [[Jacob Bates]], had long preceded him in the former Russian capital, where he performed in 1864, and since then, Moscow had welcomed several equestrian companies—among which that of [[Pierre Mayheu]], the famous Spanish rider, in 1790—but contrary to most European major cities, the great Russian metropolis didn’t have a permanent circus of its own. | The previous year, Tourniaire had exhibited his equestrian prowess in Moscow, in the manège of the Pashkov mansion (today the Russian State Library), on Mokhovaya Street. Another famous trick rider, [[Jacob Bates]], had long preceded him in the former Russian capital, where he performed in 1864, and since then, Moscow had welcomed several equestrian companies—among which that of [[Pierre Mayheu]], the famous Spanish rider, in 1790—but contrary to most European major cities, the great Russian metropolis didn’t have a permanent circus of its own. | ||

| Line 21: | Line 21: | ||

In 1853, a rich aristocrat, landowner, future oilman, and Colonel of the Guards, Ardalion Nicolayevich Novosiltsev (1816-1878), fell in love with a ravishing French equestrienne, Laura Bassin, married her, and presented her with a brand new circus. A very talented performer, Laura had been hired six years before, in 1847, by the newly created [[Russia%27s_First_National_Circus|Cirque de la Compagnie des Théâtres Impériaux]] (in short, the Imperial Circus) in St. Petersburg, which was under the management of the French equestrian [[Paul Cuzent]]. After Cuzent’s contract had expired, the success of the Imperial Circus’s productions began to wane, and Laura decided to leave the company. | In 1853, a rich aristocrat, landowner, future oilman, and Colonel of the Guards, Ardalion Nicolayevich Novosiltsev (1816-1878), fell in love with a ravishing French equestrienne, Laura Bassin, married her, and presented her with a brand new circus. A very talented performer, Laura had been hired six years before, in 1847, by the newly created [[Russia%27s_First_National_Circus|Cirque de la Compagnie des Théâtres Impériaux]] (in short, the Imperial Circus) in St. Petersburg, which was under the management of the French equestrian [[Paul Cuzent]]. After Cuzent’s contract had expired, the success of the Imperial Circus’s productions began to wane, and Laura decided to leave the company. | ||

| − | She convinced her new husband to build her a circus, but not in St. Petersburg: It was to be in Moscow—a city where, obviously, there was no competition. Open on December 18, 1853, Moscow’s first resident circus was, according to the press, elegant, well lit, and comfortably heated (an important selling point in view of the freezing Russian winters). Like most circuses of that time, it was outfitted with both a ring and a full theater stage. The new circus was located on Petrovka Street, about where today stands the back façade of the Tsum department store, | + | She convinced her new husband to build her a circus, but not in St. Petersburg: It was to be in Moscow—a city where, obviously, there was no competition. Open on December 18, 1853, Moscow’s first resident circus was, according to the press, elegant, well lit, and comfortably heated (an important selling point in view of the freezing Russian winters). Like most circuses of that time, it was outfitted with both a ring and a full theater stage. The new circus was located on Petrovka Street, about where today stands the back façade of the Tsum department store, near the Bolshoi Theatre—in what was then the theater district. |

The company of Laura Bassin’s circus was made of secondary performers from St. Petersburg’s Imperial Circus, whose average talent wouldn’t risk to cast an unwanted shadow over the French equestrienne’s brilliance—but couldn’t overly thrill the Moscovite audiences either. Evidently, Novosilstev was no showman, and his circus’s business quickly suffered from it. The life of Moscow’s first permanent circus was short: it closed its doors in 1855, and was demolished. (Undeterred, the Colonel would present his wife with another circus, in St. Petersburg this time. Although no more successful than his Moscow circus, it had a longer life: Novosiltsev eventually cut his losses by renting it for many years to visiting European circus companies.) | The company of Laura Bassin’s circus was made of secondary performers from St. Petersburg’s Imperial Circus, whose average talent wouldn’t risk to cast an unwanted shadow over the French equestrienne’s brilliance—but couldn’t overly thrill the Moscovite audiences either. Evidently, Novosilstev was no showman, and his circus’s business quickly suffered from it. The life of Moscow’s first permanent circus was short: it closed its doors in 1855, and was demolished. (Undeterred, the Colonel would present his wife with another circus, in St. Petersburg this time. Although no more successful than his Moscow circus, it had a longer life: Novosiltsev eventually cut his losses by renting it for many years to visiting European circus companies.) | ||

| Line 27: | Line 27: | ||

==Circus Hinné (1868-1892)== | ==Circus Hinné (1868-1892)== | ||

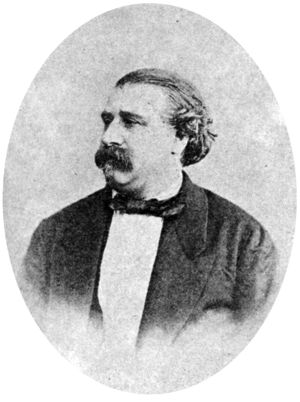

| − | [[File:Carl_Magnus_Hinné.jpg|right|thumb| | + | [[File:Carl_Magnus_Hinné.jpg|right|thumb|300px|Carl Magnus Hinné]]In 1868, the Austro-Hungarian equestrian and director [[Carl Magnus Hinné]] (1819-1890), who had built a new circus in St. Petersburg the previous year, purchased from the Princes Dolgoruky, who were embroiled into financial problems, a piece of land on Vozdvizhenka Street near the Arbat in Moscow. There, he erected a wooden construction in which his circus troupe began to perform. Its success was significant enough for Hinné to consider, the following year, to replace his temporary structure by a permanent building that would be Moscow’s counterpart of his circus in St. Petersburg. |

Hinné’s circus in St. Petersburg was making a strong impression, mostly owing to the considerable talent of its principal equestrian, his Italian brother in law [[Gaetano Ciniselli]] (1815-1881). Hinné was a great showman, and he knew he needed another gifted equestrian to headline his Moscow’s circus. He hired [[Albert Salamonsky]] (1839-1913), heir to an old and celebrated German Jewish family of equestrians and entertainers, who came to Circus Hinné with his own troupe. Both Ciniselli and Salamonsky would become major figures of Russian circus history. | Hinné’s circus in St. Petersburg was making a strong impression, mostly owing to the considerable talent of its principal equestrian, his Italian brother in law [[Gaetano Ciniselli]] (1815-1881). Hinné was a great showman, and he knew he needed another gifted equestrian to headline his Moscow’s circus. He hired [[Albert Salamonsky]] (1839-1913), heir to an old and celebrated German Jewish family of equestrians and entertainers, who came to Circus Hinné with his own troupe. Both Ciniselli and Salamonsky would become major figures of Russian circus history. | ||

| Line 41: | Line 41: | ||

===Circus Salamonsky (1880-1936)=== | ===Circus Salamonsky (1880-1936)=== | ||

| − | [[File:Albert_Salamonsky_in_old_age.jpg|thumb|left| | + | [[File:Albert_Salamonsky_in_old_age.jpg|thumb|left|300px|Albert Salamonsky]]After his successful stint at Circus Hinné, Albert Salamonsky went on touring Russia with his own traveling circus and company, and eventually settled in Odessa in 1879, where he built a permanent circus. The following year, in 1880, Muscovite newspapers announced that Salamonsky was to build a new circus in Moscow, on Tsvetnoy Boulevard. |

A wide thoroughfare in central Moscow, with a tree-planted and flowery median strip (''tsvetnoy'' means ''colorful'' in Russian), Tsvetnoy Boulevard was a popular promenade flanked by many places of amusements. One of its favorite destinations was the Panorama, housed in a circular building adjacent to the piece of land acquired by Salamonsky. ([[Vladimir Durov]] would debut as an assistant animal trainer in the menagerie of Hugo Winkler, which the latter had installed on the other side of the Boulevard, practically at the same time as the German director’s arrival.) | A wide thoroughfare in central Moscow, with a tree-planted and flowery median strip (''tsvetnoy'' means ''colorful'' in Russian), Tsvetnoy Boulevard was a popular promenade flanked by many places of amusements. One of its favorite destinations was the Panorama, housed in a circular building adjacent to the piece of land acquired by Salamonsky. ([[Vladimir Durov]] would debut as an assistant animal trainer in the menagerie of Hugo Winkler, which the latter had installed on the other side of the Boulevard, practically at the same time as the German director’s arrival.) | ||

| Line 49: | Line 49: | ||

Adjacent to the circus’s elegant façade was an aisle that housed Salamonsky’s apartment, and a café that would become, over the years, his favorite haunt—to the extent that his wife, the equestrienne Lina Schwartz, would eventually take over the management of the circus. Yet, in spite of his devastating fondness for the bottle, Salamonsky was a great artistic director, and his Moscow circus quickly gained an excellent reputation all over Europe. His liberty acts were highly praised, and he formed several outstanding horse trainers and equestrians. | Adjacent to the circus’s elegant façade was an aisle that housed Salamonsky’s apartment, and a café that would become, over the years, his favorite haunt—to the extent that his wife, the equestrienne Lina Schwartz, would eventually take over the management of the circus. Yet, in spite of his devastating fondness for the bottle, Salamonsky was a great artistic director, and his Moscow circus quickly gained an excellent reputation all over Europe. His liberty acts were highly praised, and he formed several outstanding horse trainers and equestrians. | ||

| − | + | Circus Salamonsky remained a conservatory of the grand tradition of the classic equestrian circus, an elegant place of entertainment that was Moscow’s circus of choice until the death of its founder in 1913—and in spite of the competition of the old Circus Hinné until 1892, and more importantly, of [[The_Nikitin_Brothers|Akim Nikitin]] and his brothers: In 1886, when they occupied the old Panorma building next to the circus; in 1888, when they rented Circus Hinné; and from 1911 onward, when Akim eventually built his own Muscovite circus on Bolshoya Sadovaya Street. | |

After Albert Salamonsky’s death, however, his circus fell apart. In 1914, as the winds of revolution were beginning to blow over Russia, its performers decided to elect their own director, Yury Radunsky, a circus employee with no prior managerial experience. Then came the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917; in 1919, all circuses in Russia were nationalized, including Circus Salamonsky. Many artists and directors of foreign origins—who were a vast majority in the Russian circus landscape—chose to leave the country (among them, [[Scipione Ciniselli]], the last director of the Ciniselli circuses, and even the Russian [[Nikolai Nikitin]], who had succeeded his father, Akim Nikitin, after his death in 1917). | After Albert Salamonsky’s death, however, his circus fell apart. In 1914, as the winds of revolution were beginning to blow over Russia, its performers decided to elect their own director, Yury Radunsky, a circus employee with no prior managerial experience. Then came the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917; in 1919, all circuses in Russia were nationalized, including Circus Salamonsky. Many artists and directors of foreign origins—who were a vast majority in the Russian circus landscape—chose to leave the country (among them, [[Scipione Ciniselli]], the last director of the Ciniselli circuses, and even the Russian [[Nikolai Nikitin]], who had succeeded his father, Akim Nikitin, after his death in 1917). | ||

| − | Various intellectual and artistic committees tried to define a politically correct circus, which resulted in a rather confused period, the "high point" of which was an experimental spectacle directed by Konstantin Stanislavsky and presented at the old Circus Salmonsky, ''Political Carrousel''. It was a flop of epic proportions, which at last finished to convince the cultural authorities that the management of Moscow’s two circuses (Salamonsky and Nikitin) should be given to a circus professional: They chose [[The Truzzi Dynasty|Williams Truzzi]] (1889-1931)—one of the few directors of foreign origin (albeit born in Russia) that had not abandoned ship. Truzzi took over in 1921. | + | [[File:Circus_Salamonsky_in_Moscow.jpg|thumb|right|400px|Circus Salamonsky]]Various intellectual and artistic committees tried to define a politically correct circus, which resulted in a rather confused period, the "high point" of which was an experimental spectacle directed by Konstantin Stanislavsky and presented at the old Circus Salmonsky, ''Political Carrousel''. It was a flop of epic proportions, which at last finished to convince the cultural authorities that the management of Moscow’s two circuses (Salamonsky and Nikitin) should be given to a circus professional: They chose [[The Truzzi Dynasty|Williams Truzzi]] (1889-1931)—one of the few directors of foreign origin (albeit born in Russia) that had not abandoned ship. Truzzi took over in 1921. |

Williams Truzzi’s tenure in Moscow lasted only four years (he would die in 1931, at age forty-two), but it was enough to put the circuses back on their tracks—if not to restore their luster. The two Moscow circuses competed with rather similar shows, whose originality and quality didn’t really stand out. There were not enough artists left in Russia to sustain the existence of two permanent circuses of good quality in the new capital of the USSR; Circus Nikitin was eventually closed in 1926, and transformed into a variety theater, leaving the old Circus Salamonsky alone in Moscow. | Williams Truzzi’s tenure in Moscow lasted only four years (he would die in 1931, at age forty-two), but it was enough to put the circuses back on their tracks—if not to restore their luster. The two Moscow circuses competed with rather similar shows, whose originality and quality didn’t really stand out. There were not enough artists left in Russia to sustain the existence of two permanent circuses of good quality in the new capital of the USSR; Circus Nikitin was eventually closed in 1926, and transformed into a variety theater, leaving the old Circus Salamonsky alone in Moscow. | ||

| Line 62: | Line 62: | ||

The new circus, which opened in 1937, was officially named ''Moscow State Circus of the Order of Lenin''—although the only sign on its façade was the word ''Tsirk'' (Circus). To its Muscovite audiences, however, it was simply ''The Circus on Tsvetnoy Boulevard''. Its rather bland façade had lost indeed the aristocratic looks of the old Circus Salamonsky, but its house had retained a classic elegance, and with 1,500 seats (gone were the promenade and the narrow benches of the popular section), it had an atmosphere of warmth and intimacy. | The new circus, which opened in 1937, was officially named ''Moscow State Circus of the Order of Lenin''—although the only sign on its façade was the word ''Tsirk'' (Circus). To its Muscovite audiences, however, it was simply ''The Circus on Tsvetnoy Boulevard''. Its rather bland façade had lost indeed the aristocratic looks of the old Circus Salamonsky, but its house had retained a classic elegance, and with 1,500 seats (gone were the promenade and the narrow benches of the popular section), it had an atmosphere of warmth and intimacy. | ||

| + | |||

By then, Moscow’s [[State College for Circus and Variety Arts]], the USSR’s first state circus school, had been instituted (in 1929), and a new generation of highly skilled Russian circus artists was beginning to pump new blood into a resurecting Russian circus. The Circus on Tsvetnoy Boulevard became the epicenter of this circus renaissance, and only the best acts of the land were invited to perform in what was now the Soviet Circus’s flagship. To Soviet circus artists, playing on Tsvetnoy Boulevard quickly became a badge of artistic achievement. | By then, Moscow’s [[State College for Circus and Variety Arts]], the USSR’s first state circus school, had been instituted (in 1929), and a new generation of highly skilled Russian circus artists was beginning to pump new blood into a resurecting Russian circus. The Circus on Tsvetnoy Boulevard became the epicenter of this circus renaissance, and only the best acts of the land were invited to perform in what was now the Soviet Circus’s flagship. To Soviet circus artists, playing on Tsvetnoy Boulevard quickly became a badge of artistic achievement. | ||

| − | |||

| − | [[File:Tsvetnoy_Blvd_(c.1970).jpg|thumb|left| | + | This renewal of interest in the circus arts was epitomized by the creation in 1944 of the first "All-Union Circus Competition", which was held on Tsvetnoy Boulevard. It became an annual event that would have a growing importance in the Soviet circus system: To win the competition meant working in the best circus programs of the USSR, and most importantly, starting in the 1960s, to get an opportunity to participate in the highly rewarding Soviet Circus’s international tours with the so-called "[[Moscow Circus]]" companies. |

| + | |||

| + | [[File:Tsvetnoy_Blvd_(c.1970).jpg|thumb|left|400px|The Circus On Tsvetnoy Boulevard]]Among the many Soviet circus stars that made their mark at the Circus on Tsvetnoy Boulevard, two clowns stand out: the diminutive and extremely popular [[Karandash]] (Mikhail Rumyantsev, 1901-1983), one of the first graduates of the State College for Circus and Variety Arts, who provided Muscovites with much needed laughter during the somber years of WWII; and his protégé, the beloved [[Yury Nikulin]] (1921-1997), star of the ring as well as of the silver screen, who was given the management of the Circus in 1983. Under Nikulin’s tenure, the Circus on Tsvetnoy Boulevard was to undergo drastic changes. | ||

| − | In 1971, a brand new, state-of-the-art circus opened its doors at Verdnasky Avenue, on Lenin Hill near the University of Moscow. With its 3,300 seats and technical amenities hitherto unknown to the circus world. The ''Moscow Circus On Lenin Hill'', as it was officially named (it was popularly known as the "New Circus"), was a little distant from the center of Moscow, but even so, it took over the place of the Circus on Tsvetnoy Boulevard as the Soviet Circus’s official flagship—although not its place as the Muscovites’ favorite circus. | + | In 1971, a brand new, state-of-the-art circus had opened its doors at Verdnasky Avenue, on Lenin Hill near the University of Moscow. With its 3,300 seats and technical amenities hitherto unknown to the circus world. The ''Moscow Circus On Lenin Hill'', as it was officially named (it was popularly known as the "New Circus"), was a little distant from the center of Moscow, but even so, it took over the place of the Circus on Tsvetnoy Boulevard as the Soviet Circus’s official flagship—although not its place as the Muscovites’ favorite circus. |

The Soviet Circus was then reaching its artistic peak; supported by the State, its performers were producing the world’s most extraordinary and innovative acts, for which nothing seemed impossible. The Circus on Tsvetnoy Boulevard—which was now nicknamed the "Old Circus"—was ill-equipped to accommodate the Soviet artists’ most spectacular and original circus acts, notably their huge and often intricate aerial acts that required large space and great heights—not to mention some exceptional attractions such as [[Margarita Nazarova]]’s swimming tigers, which could be presented only in the New Circus’s huge water basin. | The Soviet Circus was then reaching its artistic peak; supported by the State, its performers were producing the world’s most extraordinary and innovative acts, for which nothing seemed impossible. The Circus on Tsvetnoy Boulevard—which was now nicknamed the "Old Circus"—was ill-equipped to accommodate the Soviet artists’ most spectacular and original circus acts, notably their huge and often intricate aerial acts that required large space and great heights—not to mention some exceptional attractions such as [[Margarita Nazarova]]’s swimming tigers, which could be presented only in the New Circus’s huge water basin. | ||

| Line 75: | Line 77: | ||

===Circus Nikulin (1989-present)=== | ===Circus Nikulin (1989-present)=== | ||

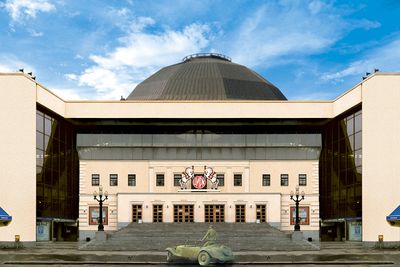

| − | [[File:Circus_Nikulin_(façade).jpg|thumb|right| | + | [[File:Circus_Nikulin_(façade).jpg|thumb|right|400px|Circus Nikulin]]The new Circus on Tsvetnoy Boulevard opened its doors September 29, 1989. To everybody’s relief, the old façade still could be seen, even though it was framed within a giant glass front. Another sign of continuity was the house, which resembled the old one, with its characteristic columns and color scheme—and had retained its warmth—although it had been significantly enlarged to a seating capacity of 2,000, and equipped with a much higher cupola, allowing the presentation of the most elaborate aerial acts. Backstage, the practice ring, the many workshops, modern dressing rooms and animal quarters, offices and rental spaces for businesses made it a superb circus tool. |

It was not the "Old Circus" anymore, and as a matter of fact, the Circus on Tsvetnoy Boulevard quickly regained its status as Moscow’s premier circus. In 1991, Yury Nikulin celebrated his 70th birthday in the ring of his new circus, in presence of the Mayor of Moscow and a huge crowd of personalities of the Russian circus, the arts, and politics. The Soviet Union had just collapsed, and as much as this joyous celebration, the Circus on Tsvetnoy Boulevard became symbolic of a new era. | It was not the "Old Circus" anymore, and as a matter of fact, the Circus on Tsvetnoy Boulevard quickly regained its status as Moscow’s premier circus. In 1991, Yury Nikulin celebrated his 70th birthday in the ring of his new circus, in presence of the Mayor of Moscow and a huge crowd of personalities of the Russian circus, the arts, and politics. The Soviet Union had just collapsed, and as much as this joyous celebration, the Circus on Tsvetnoy Boulevard became symbolic of a new era. | ||

| Line 107: | Line 109: | ||

===Circus Nikitin (1911-1926)=== | ===Circus Nikitin (1911-1926)=== | ||

| − | [[File:Akim_Nikitin_1909.jpg|thumb|right| | + | [[File:Akim_Nikitin_1909.jpg|thumb|right|300px|Akim Nikitin]]By the late 1890, Piotr had retired from the family enterprise and Akim was alone at the helm, overseeing a growing circus empire with buildings in Tiflis (today Tbilisi in Georgia, which was the Nikitins’ home base), Baku and Astrakhan (where Circus Nikitin spent the winter season), Tsaritsyn (today Volgograd), Saratov, Samara, Kazan, Nizhniy-Novgorod, Ivanovo-Voznesensk, and Kharkov. A true showman and the most ambitious of the brothers, Akim needed now the cherry on his cake: A permanent circus in Moscow. The fact that his Tiflis flagship circus had burned down in 1910 probably persuaded him to make the big jump. |

Akim found a piece of land near Triumfalnaya Square on Bolshaya Sadovaya Street, a large avenue northwest of central Moscow, and he commissioned the architect Bogdan Mikhailovich Nilus, a well-known proponent of the Art Nouveau architectural movement, to build him a state-of-the-art circus. Open in 1911, Circus Nikitin was outfitted with a revolving ring that could also sink into a water basin, following the example of Paris’s famous [[Nouveau Cirque (Paris)|Nouveau Cirque]], and covered with a removable coco mat instead of soil and sawdust—the first time this kind of ring cover was used in Russia, and a clear sign that Circus Nikitin didn’t intend to be a classical equestrian circus like Salamonsky’s. The building had also an imposing façade that made it quite conspicuous to passersby. | Akim found a piece of land near Triumfalnaya Square on Bolshaya Sadovaya Street, a large avenue northwest of central Moscow, and he commissioned the architect Bogdan Mikhailovich Nilus, a well-known proponent of the Art Nouveau architectural movement, to build him a state-of-the-art circus. Open in 1911, Circus Nikitin was outfitted with a revolving ring that could also sink into a water basin, following the example of Paris’s famous [[Nouveau Cirque (Paris)|Nouveau Cirque]], and covered with a removable coco mat instead of soil and sawdust—the first time this kind of ring cover was used in Russia, and a clear sign that Circus Nikitin didn’t intend to be a classical equestrian circus like Salamonsky’s. The building had also an imposing façade that made it quite conspicuous to passersby. | ||

| Line 127: | Line 129: | ||

At the end of the 1960s, Brezhnev ordered the construction of a new, ultramodern circus in Moscow, a large building equipped with ground-breaking technical amenities, which would be the flagship of the Soviet Circus. Yakov Belopolsky, the most famous architect of the Brezhnev era and author of many official buildings and monuments, was given the project. He surrounded himself with three other architects, E. Boulikh, S. Feoksitov, and V. Khavin—who were probably more versed into the specificities of theater architecture and its technical requirements than Belopolsky, and perhaps also abler to develop new technical tools specific to the circus. | At the end of the 1960s, Brezhnev ordered the construction of a new, ultramodern circus in Moscow, a large building equipped with ground-breaking technical amenities, which would be the flagship of the Soviet Circus. Yakov Belopolsky, the most famous architect of the Brezhnev era and author of many official buildings and monuments, was given the project. He surrounded himself with three other architects, E. Boulikh, S. Feoksitov, and V. Khavin—who were probably more versed into the specificities of theater architecture and its technical requirements than Belopolsky, and perhaps also abler to develop new technical tools specific to the circus. | ||

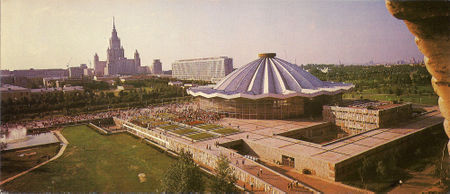

| − | [[File:Bolshoi_Circus_1974.jpg|thumb|right| | + | [[File:Bolshoi_Circus_1974.jpg|thumb|right|450px|The Bolshoi Circus]]Located on Lenin Hill (today Sparrows Hill), on Vernadsky Avenue, southwest of central Moscow, the “New Circus” (as it was called, although its official name was Moscow Circus On Lenin Hill), opened its doors April 30, 1971. With 3,300 seats, it is still today the world’s largest indoor circus, yet its technical installations are what make it truly exceptional. Among other amenities, the building includes a rehearsal ring backstage in a space large enough to accommodate big aerial acts; a large stage above the artists’ entrance to the ring, connectable to the ring through a telescopic staircase that comes down electrically from under the stage; the possibility for aerialists to reach their apparatus from the ceiling; and rooms at various temperatures for the keep of the different animal species. |

The jewel of the crown, however, is the system of interchangeable rings. They are located in a vast basement under the house, around a hydraulic elevator placed at their center, and can be rolled in and brought up at house level as need be. There is a traditional equestrian ring (covered with a special rubber mat, the first that was used in any circus, and which has become standard in Russia); a three-meter-deep water basin, equipped with fountains and underwater lighting; an ice ring; a wooden floor with trapdoors for magicians; and a lighted floor with changeable colors. The system not only allows to quickly adapt the ring to any need, it also allows the installation of cumbersome props on a specific ring while another is in use. | The jewel of the crown, however, is the system of interchangeable rings. They are located in a vast basement under the house, around a hydraulic elevator placed at their center, and can be rolled in and brought up at house level as need be. There is a traditional equestrian ring (covered with a special rubber mat, the first that was used in any circus, and which has become standard in Russia); a three-meter-deep water basin, equipped with fountains and underwater lighting; an ice ring; a wooden floor with trapdoors for magicians; and a lighted floor with changeable colors. The system not only allows to quickly adapt the ring to any need, it also allows the installation of cumbersome props on a specific ring while another is in use. | ||

| Line 141: | Line 143: | ||

==Suggested Reading== | ==Suggested Reading== | ||

| − | * Yury Dmitriev, ''My Old Circus, Tsvetnoy Boulevard'' (Moscow, Lazur, 2000) — In Russian — ISBN 5-85806-028-5 | + | * Yury Dmitriev, ''Мой старый Цирк Бульвар Цветной'' (''My Old Circus, Tsvetnoy Boulevard'') (Moscow, Lazur, 2000) — In Russian — ISBN 5-85806-028-5 |

| − | * | + | * Rudolf Evgenievich Slavskiy, ''Братья Никитины'' (''The Brothers Nikitin'') (Mосква, Искусство, 1987) — In Russian. |

==See Also== | ==See Also== | ||

Latest revision as of 20:55, 25 January 2024

By Dominique Jando

Although the name Moscow Circus is familiar to the public all over the world, there has never been one specific “Moscow Circus” whose troupe toured internationally. The name was a generic term for the circus shows from the USSR traveling abroad during the Soviet Era. It has, over time, become synonymous with “Russian circus.” Yet, there are today (2024) two resident circuses in Moscow, Circus Nikulin on Tsvetnoy Boulevard, and the Bolshoi Circus (bolshoi means big, in Russian) on Vernadsky Avenue—and there have been indeed several others before them.

Contents

- 1 Jacques Tourniaire

- 2 Zagoskin’s Summer Circus (1830-1832)

- 3 Laura Bassin’s Circus (1853-1855)

- 4 Circus Hinné (1868-1892)

- 5 The Circus on Tsvetnoy Boulevard (1880-present)

- 6 Circus Nikitin (1883, 1886-1887, 1888-1889, 1911-1926)

- 7 The Bolshoi Circus (1971-present)

- 8 Suggested Reading

- 9 See Also

- 10 Image Gallery

Jacques Tourniaire

The first circus built in Russia was established by the French equestrian Jacques Tourniaire (1772-1829), who settled in 1827 in what was then the Russian capital, St. Petersburg. The building, designed by the architect Smaragd Shustov and named Cirque Olympique, was located near the Fontanka canal, practically where St. Petersburg’s Circus Ciniselli stands today. Tourniaire’s circus had only a short existence: it was bought back by the government of St. Petersburg in 1828 to be transformed into a theater. Still, the event didn’t fail to catch the attention of the Muscovites, who always took exception to the influence of Peter The Great’s Baltic capital.

The previous year, Tourniaire had exhibited his equestrian prowess in Moscow, in the manège of the Pashkov mansion (today the Russian State Library), on Mokhovaya Street. Another famous trickAny specific exercise in a circus act. rider, Jacob Bates, had long preceded him in the former Russian capital, where he performed in 1864, and since then, Moscow had welcomed several equestrian companies—among which that of Pierre Mayheu, the famous Spanish rider, in 1790—but contrary to most European major cities, the great Russian metropolis didn’t have a permanent circus of its own.

Zagoskin’s Summer Circus (1830-1832)

In 1830, Mikhail Zagoskin, a popular novelist who was Moscow’s Director of the Theaters, supported the creation of a summer circus in the Neskuchny Garden, on the banks of the Moskva River, southwest of central Moscow. The circus, which was probably a light wooden construction(French) A temporary circus building, originally made of wood and canvas, and later, of steel elements supporting a canvas top and wooden wall. Also known as a "semi-construction.", lasted only three seasons. For the ensuing twenty years, Russian circus history was written exclusively in St. Petersburg: Although Moscow was still the commercial hub of Tsarist Russia, the giant city didn’t have yet the rich cosmopolitan atmosphere of the Russian capital, or its cultural diversity.

German, Italian and, mostly, French influences were quite noticeable in St. Petersburg, a city wide open on Western Europe, as its builder, Peter The Great, had wanted it. By reaction, Moscow took pride in its being the true heart of eternal Russia, conservative, religious and nationalistic. Even though its wealth attracted traveling entertainers as much as entrepreneurs and merchants, the city was particularly slow in attuning itself to the rest of Europe.

Laura Bassin’s Circus (1853-1855)

In 1853, a rich aristocrat, landowner, future oilman, and Colonel of the Guards, Ardalion Nicolayevich Novosiltsev (1816-1878), fell in love with a ravishing French equestrienneA female equestrian, or horse trainer, horse presenter, or acrobat on horseback., Laura Bassin, married her, and presented her with a brand new circus. A very talented performer, Laura had been hired six years before, in 1847, by the newly created Cirque de la Compagnie des Théâtres Impériaux (in short, the Imperial Circus) in St. Petersburg, which was under the management of the French equestrian Paul Cuzent. After Cuzent’s contract had expired, the success of the Imperial Circus’s productions began to wane, and Laura decided to leave the company.

She convinced her new husband to build her a circus, but not in St. Petersburg: It was to be in Moscow—a city where, obviously, there was no competition. Open on December 18, 1853, Moscow’s first resident circus was, according to the press, elegant, well lit, and comfortably heated (an important selling point in view of the freezing Russian winters). Like most circuses of that time, it was outfitted with both a ring and a full theater stage. The new circus was located on Petrovka Street, about where today stands the back façade of the Tsum department store, near the Bolshoi Theatre—in what was then the theater district.

The company of Laura Bassin’s circus was made of secondary performers from St. Petersburg’s Imperial Circus, whose average talent wouldn’t risk to cast an unwanted shadow over the French equestrienneA female equestrian, or horse trainer, horse presenter, or acrobat on horseback.’s brilliance—but couldn’t overly thrill the Moscovite audiences either. Evidently, Novosilstev was no showman, and his circus’s business quickly suffered from it. The life of Moscow’s first permanent circus was short: it closed its doors in 1855, and was demolished. (Undeterred, the Colonel would present his wife with another circus, in St. Petersburg this time. Although no more successful than his Moscow circus, it had a longer life: Novosiltsev eventually cut his losses by renting it for many years to visiting European circus companies.)

Circus Hinné (1868-1892)

In 1868, the Austro-Hungarian equestrian and director Carl Magnus Hinné (1819-1890), who had built a new circus in St. Petersburg the previous year, purchased from the Princes Dolgoruky, who were embroiled into financial problems, a piece of land on Vozdvizhenka Street near the Arbat in Moscow. There, he erected a wooden construction(French) A temporary circus building, originally made of wood and canvas, and later, of steel elements supporting a canvas top and wooden wall. Also known as a "semi-construction." in which his circus troupe began to perform. Its success was significant enough for Hinné to consider, the following year, to replace his temporary structure by a permanent building that would be Moscow’s counterpart of his circus in St. Petersburg.Hinné’s circus in St. Petersburg was making a strong impression, mostly owing to the considerable talent of its principal equestrian, his Italian brother in law Gaetano Ciniselli (1815-1881). Hinné was a great showman, and he knew he needed another gifted equestrian to headline his Moscow’s circus. He hired Albert Salamonsky (1839-1913), heir to an old and celebrated German Jewish family of equestrians and entertainers, who came to Circus Hinné with his own troupe. Both Ciniselli and Salamonsky would become major figures of Russian circus history.

In 1875, Carl Magnus Hinné, who had amassed a substantial wealth during his many travels as a circus owner, decided to retire from the circus business. He left the management of his two Russian circuses to his brother in law, Gaetano Ciniselli. Born in Milan, Italy, Ciniselli was already an experienced manager and a brilliant producer. His elegance and, at times, his extravagant sense of showmanship formed a perfect combination, in symbiosis with the luxurious and sometimes excessive tastes of his aristocratic audiences in St. Petersburg.

The Russian capital was Ciniselli’s city of choice: In 1877, he would replace the old circus that Hinné had built on Karavannaya Square, near Nevsky Prospekt, with a superb building on the Fontanka Canal, which is still active today. He would never give the same attention to his Moscow circus, and after his death, his sons mostly rented it to visiting—albeit excellent—circus companies. The circus never truly acquired the Ciniselli stamp: It became known in Moscow as "the old Hinné Circus."

It remained active until 1892, at which time another flamboyant Italian director who had become a major figure of the Russian circus, Massimiliano Truzzi, was renting it. Then, the old Circus Hinné was demolished and on its place, the wealthy merchant Arseny Morosov erected an extravagant and ostentatious neo-Moorish mansion, which is still today one of Moscow’s landmarks and is used as a Reception House by the Government of the Russian Federation.

The Circus on Tsvetnoy Boulevard (1880-present)

Circus Salamonsky (1880-1936)

After his successful stint at Circus Hinné, Albert Salamonsky went on touring Russia with his own traveling circus and company, and eventually settled in Odessa in 1879, where he built a permanent circus. The following year, in 1880, Muscovite newspapers announced that Salamonsky was to build a new circus in Moscow, on Tsvetnoy Boulevard.A wide thoroughfare in central Moscow, with a tree-planted and flowery median strip (tsvetnoy means colorful in Russian), Tsvetnoy Boulevard was a popular promenade flanked by many places of amusements. One of its favorite destinations was the Panorama, housed in a circular building adjacent to the piece of land acquired by Salamonsky. (Vladimir Durov would debut as an assistant animal trainer in the menagerie of Hugo Winkler, which the latter had installed on the other side of the Boulevard, practically at the same time as the German director’s arrival.)

The new circus, designed by the architect A.H. Weber, was completed October 12, 1880 and opened its doors eight days later. The imposing building could accommodate 4,000 spectators, a large part of whom stood in a gallery that was located at the back of the house, above the foyer. It was a circular amphitheater whose seats surrounded the ring: It didn’t have a stage, following in that the model of Paris’s circuses, the Cirque des Champs-Elysées, the Cirque d’Hiver, and the Cirque Fermando. The stables, which had room for some one hundred horses, were open to the public at intermission.

Adjacent to the circus’s elegant façade was an aisle that housed Salamonsky’s apartment, and a café that would become, over the years, his favorite haunt—to the extent that his wife, the equestrienneA female equestrian, or horse trainer, horse presenter, or acrobat on horseback. Lina Schwartz, would eventually take over the management of the circus. Yet, in spite of his devastating fondness for the bottle, Salamonsky was a great artistic director, and his Moscow circus quickly gained an excellent reputation all over Europe. His liberty"Liberty act", "Horses at liberty": Unmounted horses presented from the center of the ring by an equestrian directing his charges with his voice, body movements, and signals from a ''chambrière'' (French), or long whip. acts were highly praised, and he formed several outstanding horse trainers and equestrians.

Circus Salamonsky remained a conservatory of the grand tradition of the classic equestrian circus, an elegant place of entertainment that was Moscow’s circus of choice until the death of its founder in 1913—and in spite of the competition of the old Circus Hinné until 1892, and more importantly, of Akim Nikitin and his brothers: In 1886, when they occupied the old Panorma building next to the circus; in 1888, when they rented Circus Hinné; and from 1911 onward, when Akim eventually built his own Muscovite circus on Bolshoya Sadovaya Street.

After Albert Salamonsky’s death, however, his circus fell apart. In 1914, as the winds of revolution were beginning to blow over Russia, its performers decided to elect their own director, Yury Radunsky, a circus employee with no prior managerial experience. Then came the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917; in 1919, all circuses in Russia were nationalized, including Circus Salamonsky. Many artists and directors of foreign origins—who were a vast majority in the Russian circus landscape—chose to leave the country (among them, Scipione Ciniselli, the last director of the Ciniselli circuses, and even the Russian Nikolai Nikitin, who had succeeded his father, Akim Nikitin, after his death in 1917).

Various intellectual and artistic committees tried to define a politically correct circus, which resulted in a rather confused period, the "high point" of which was an experimental spectacle directed by Konstantin Stanislavsky and presented at the old Circus Salmonsky, Political Carrousel. It was a flop of epic proportions, which at last finished to convince the cultural authorities that the management of Moscow’s two circuses (Salamonsky and Nikitin) should be given to a circus professional: They chose Williams Truzzi (1889-1931)—one of the few directors of foreign origin (albeit born in Russia) that had not abandoned ship. Truzzi took over in 1921.Williams Truzzi’s tenure in Moscow lasted only four years (he would die in 1931, at age forty-two), but it was enough to put the circuses back on their tracks—if not to restore their luster. The two Moscow circuses competed with rather similar shows, whose originality and quality didn’t really stand out. There were not enough artists left in Russia to sustain the existence of two permanent circuses of good quality in the new capital of the USSR; Circus Nikitin was eventually closed in 1926, and transformed into a variety theater, leaving the old Circus Salamonsky alone in Moscow.

During these times, the Soviet government’s Committee for the Arts, which had no clear vision for the circus as a performing art, continued nonetheless to experiment with a medium they didn’t really understand. Finally, after the failure of several government-sponsored productions on Tsvetnoy Boulevard, the Soviet circus as a whole was placed in 1936 under the control of a specific and knowledgeable agency, the Circus Central Management (the forerunner of SoyuzGosTsirk, the Union of State Circuses). One of its first actions—and perhaps a symbolic one—was to destroy the old Salamonsky building, and to erect a brand new circus on its spot.

The Moscow State Circus of the Order of Lenin (1937-1985)

The new circus, which opened in 1937, was officially named Moscow State Circus of the Order of Lenin—although the only sign on its façade was the word Tsirk (Circus). To its Muscovite audiences, however, it was simply The Circus on Tsvetnoy Boulevard. Its rather bland façade had lost indeed the aristocratic looks of the old Circus Salamonsky, but its house had retained a classic elegance, and with 1,500 seats (gone were the promenade and the narrow benches of the popular section), it had an atmosphere of warmth and intimacy.

By then, Moscow’s State College for Circus and Variety Arts, the USSR’s first state circus school, had been instituted (in 1929), and a new generation of highly skilled Russian circus artists was beginning to pump new blood into a resurecting Russian circus. The Circus on Tsvetnoy Boulevard became the epicenter of this circus renaissance, and only the best acts of the land were invited to perform in what was now the Soviet Circus’s flagship. To Soviet circus artists, playing on Tsvetnoy Boulevard quickly became a badge of artistic achievement.

This renewal of interest in the circus arts was epitomized by the creation in 1944 of the first "All-Union Circus Competition", which was held on Tsvetnoy Boulevard. It became an annual event that would have a growing importance in the Soviet circus system: To win the competition meant working in the best circus programs of the USSR, and most importantly, starting in the 1960s, to get an opportunity to participate in the highly rewarding Soviet Circus’s international tours with the so-called "Moscow Circus" companies.

Among the many Soviet circus stars that made their mark at the Circus on Tsvetnoy Boulevard, two clowns stand out: the diminutive and extremely popular Karandash (Mikhail Rumyantsev, 1901-1983), one of the first graduates of the State College for Circus and Variety Arts, who provided Muscovites with much needed laughter during the somber years of WWII; and his protégé, the beloved Yury Nikulin (1921-1997), star of the ring as well as of the silver screen, who was given the management of the Circus in 1983. Under Nikulin’s tenure, the Circus on Tsvetnoy Boulevard was to undergo drastic changes.In 1971, a brand new, state-of-the-art circus had opened its doors at Verdnasky Avenue, on Lenin Hill near the University of Moscow. With its 3,300 seats and technical amenities hitherto unknown to the circus world. The Moscow Circus On Lenin Hill, as it was officially named (it was popularly known as the "New Circus"), was a little distant from the center of Moscow, but even so, it took over the place of the Circus on Tsvetnoy Boulevard as the Soviet Circus’s official flagship—although not its place as the Muscovites’ favorite circus.

The Soviet Circus was then reaching its artistic peak; supported by the State, its performers were producing the world’s most extraordinary and innovative acts, for which nothing seemed impossible. The Circus on Tsvetnoy Boulevard—which was now nicknamed the "Old Circus"—was ill-equipped to accommodate the Soviet artists’ most spectacular and original circus acts, notably their huge and often intricate aerial acts that required large space and great heights—not to mention some exceptional attractions such as Margarita Nazarova’s swimming tigers, which could be presented only in the New Circus’s huge water basin.

When Yury Nikulin took the reins of the Circus on Tsvetnoy Boulevard, the Soviet Union was opening to the world and had not sunk yet (at least visibly) into the economic nadir that would lead to its collapse. Yury Nikulin chose that time to have a brand new circus built on Tsvetnoy Boulevard. The Old Circus gave an emotional last performance on August 13, 1985, and was entirely demolished. A Finnish company (a sign of the drastic changes occurring in the USSR) was given the task of building a new, state-of-the-art circus in its place on Tsvetnoy Boulevard.

Circus Nikulin (1989-present)

The new Circus on Tsvetnoy Boulevard opened its doors September 29, 1989. To everybody’s relief, the old façade still could be seen, even though it was framed within a giant glass front. Another sign of continuity was the house, which resembled the old one, with its characteristic columns and color scheme—and had retained its warmth—although it had been significantly enlarged to a seating capacity of 2,000, and equipped with a much higher cupola, allowing the presentation of the most elaborate aerial acts. Backstage, the practice ring, the many workshops, modern dressing rooms and animal quarters, offices and rental spaces for businesses made it a superb circus tool.It was not the "Old Circus" anymore, and as a matter of fact, the Circus on Tsvetnoy Boulevard quickly regained its status as Moscow’s premier circus. In 1991, Yury Nikulin celebrated his 70th birthday in the ring of his new circus, in presence of the Mayor of Moscow and a huge crowd of personalities of the Russian circus, the arts, and politics. The Soviet Union had just collapsed, and as much as this joyous celebration, the Circus on Tsvetnoy Boulevard became symbolic of a new era.

Yury Nikulin passed away in 1997, and a large crowd of Muscovites lined up to pay their last respects to the legendary clown and actor, whose body lay in state in the ring of Tsvetnoy Boulevard. His son, Maxim Nikulin, a former journalist who was already involved in the management of the circus, succeeded him. That same year, the Circus on Tsvetnoy Boulevard was officially renamed Circus Nikulin of Moscow in honor of the beloved clown who had so successfully helped it to pass the threshold of a new Russia.

Circus Nikitin (1883, 1886-1887, 1888-1889, 1911-1926)

The brothers Nikitin, Dmitri (1835-1918), Akim (1843-1917), and Piotr (1846-1921), were the son of Aleksandr Nikitin, a serf bounded to one of the vast lands belonging to the Crown. In 1842, Tsar Nicholas I established the "quit-rent" system, which allowed the serfs to leave the land to which they were attached in exchange for a rent paid to their landowner, thus beginning to ease the condition of the serfs in the Imperial estates.Aleksandr Nikitin took advantage of this opportunity: He hit the road with an old barrel organ and became a traveling entertainer. His sons were quickly put to work in his budding show, enhancing his performance with some tumbling, juggling, and exercises of strength. When serfdom was definitely abolished in 1862, Dmitri, Akim and Piotr went to work in the balagans(Russian) Fairground booths or theaters., the traveling theaters that flourished on the Russian fairgrounds. The brothers eventually created their own puppet and variety show and became independent fairground entrepreneurs.

Even though they were illiterate, the brothers Nikitin were ambitious and shrewd, and since traveling entertainers have long learned ways to fend for themselves, they mastered the art of cunning in the balagans(Russian) Fairground booths or theaters.. In 1873, the sons of the former serf had gathered enough money to start their own traveling circus, the Brothers Nikitin’s Russian Circus, in Penza, south of Kazan. Three years later, they built in Saratov, a city southwest of Russia on the Volga River, the first of a series of provincial circus buildings.

Nikitin Hippodrome at Khodinskoe Pole (1883)

In the summer of 1883, for the festivities marking the coronation of Tsar Alexander III, the Nikitins were invited to build a temporary "Hippodrome" in Khodynskoe Pole, a vast and popular field in northwest Moscow where military maneuvers usually took place. (An airport occupied part of it after WWII; it has been recently replaced by a giant shopping and entertainment mall.) The Nikitins’ Hippodrome was conceived loosely after the fashionable Parisian Hippodromes of the 19th century: Not to be confused with racetracks, these were large open-air or partially covered arenas in which equestrian presentations and other circus acts were presented in oversize spectacles.

The Nikitin Hippodrome was a light wooden structure, an open-air arena whose arrangement owed more to P.T. Barnum’s interpretation of Franconi’s concept than to the Parisian original: It was outfitted with two rings separated by a center stage and surrounded by a hippodrome track. There, the Nikitins staged an equestrian spectacular based on popular Russian legends. It was quite successful, and the City of Moscow awarded them a medal—one of the many medals Akim Nikitin would later proudly display on his evening coat. Then, the Nikitins left Moscow and resumed their Russian travels.

Circus Nikitin On Tsvetnoy Boulevard (1886-1887)

Yet, the Nikitins had got a taste of the great Russian metropolis’s riches, and these interested them much more than a mere artistic success. In 1886, they returned to Moscow and bought the old Panorama building on Tsvetnoy Boulevard, just next to Circus Salamonsky, and installed their circus in it. Their success was substantial enough to entice Albert Salamonsky, who, understandably, was not especially amused, to buy the building back at the end of the Nikitins’ season for a whooping 30,000 rubles—quite a generous sum at the time. The deal included a written assurance that the Nikitins would refrain in the future from competing with Salamonsky in Moscow.

The following season, Salamonsky used the building to present exhibitions of equestrian dressage, and then disposed of it. The story doesn’t say if he recouped his investment—but chances are that he did not! (The building’s basic structure has survived over the years under various incarnations; its walls house today the Mir Theater.) Then, Dmitri Nikitin left the family circus to create his own enterprise, the Panoptikon—probably a peep show with moving images. The wily Akim and Piotr decided to return to Moscow.

Circus Nikitin At Circus Hinné (1888-1889)

For the 1888-1889 season, Akim and Piotr Nikitin rented the old Circus Hinné on Vozdvizhenka Street. Furious, Salamonsky went to see them and brandished to their face the letter of agreement signed the previous year. Akim and Piotr gleefully told him to check the letter: It had been signed by Dmitri alone, who had no participation in the circus anymore—and therefore, Akim and Piotr were not bounded by it… There was not much Salamonsky could do besides swallowing his pride, and, to his chagrin, the Nikitins went on with their season. Unfortunately it didn’t prove as successful as their previous stay in Moscow and at the end of the run, they left Moscow and resumed their tours of the Russian provinces.

Circus Nikitin (1911-1926)

By the late 1890, Piotr had retired from the family enterprise and Akim was alone at the helm, overseeing a growing circus empire with buildings in Tiflis (today Tbilisi in Georgia, which was the Nikitins’ home base), Baku and Astrakhan (where Circus Nikitin spent the winter season), Tsaritsyn (today Volgograd), Saratov, Samara, Kazan, Nizhniy-Novgorod, Ivanovo-Voznesensk, and Kharkov. A true showman and the most ambitious of the brothers, Akim needed now the cherry on his cake: A permanent circus in Moscow. The fact that his Tiflis flagship circus had burned down in 1910 probably persuaded him to make the big jump.Akim found a piece of land near Triumfalnaya Square on Bolshaya Sadovaya Street, a large avenue northwest of central Moscow, and he commissioned the architect Bogdan Mikhailovich Nilus, a well-known proponent of the Art Nouveau architectural movement, to build him a state-of-the-art circus. Open in 1911, Circus Nikitin was outfitted with a revolving ring that could also sink into a water basin, following the example of Paris’s famous Nouveau Cirque, and covered with a removable coco mat instead of soil and sawdust—the first time this kind of ring cover was used in Russia, and a clear sign that Circus Nikitin didn’t intend to be a classical equestrian circus like Salamonsky’s. The building had also an imposing façade that made it quite conspicuous to passersby.

The star of Circus Nikitin’s opening show was the young clownGeneric term for all clowns and augustes. '''Specific:''' In Europe, the elegant, whiteface character who plays the role of the straight man to the Auguste in a clown team.-acrobat Vitaly Lazarenko (1890-1939), who would become a legendary circus figure of the early Soviet regime. While Circus Salamonsky would remain for two more years Moscow’s elegant circus, where the grand tradition of classical equestrian circus was still celebrated, Akim Nikitin favored lavish pantomimes (notably water pantomimes), exotic animals, and spectacular daredevil acts. In 1914, Lazarenko made the newspapers’ front page and the burgeoning movie news when he somersaulted over three elephants at Circus Nikitin!

After Salamonsky’s death in 1913, his circus quickly went amiss, and the two Moscow circuses set off into a direct competition, each one trying to surpass the other with similar shows. In his wonderful satire of the emerging Communist regime, Heart Of A Dog (1923), the famous Russian novelist Mikhail Bulgakov, who had a fondness for circus and variety, describes the dilemma facing his two main protagonists. Wishing to go to the circus, and having to choose between the old Circus Salamonsky and Circus Nikitin, they lament that both circuses are off-putting: They have become equally vulgar.

This of course was written after the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917—the year, too, when Akim Nikitin passed away. His son, Nikolai (1887-1963), a talented juggler on horseback, took over the management of his father’s enterprise, but when all circuses were nationalized in 1919, he left the country (as did many directors and artists) and went on to perform his act in Italy. Then, after a long, uncertain period under the management of the Soviet Committee for the Arts, Circus Nikitin was placed under the management of Williams Truzzi in 1921, who was also put in charge of the old Circus Salamonsky.Nikolai Nikitin returned to the Soviet Union in 1922, but only to continue his career as a juggler on horseback. He would not have any further connection with the circuses his father built. As for Truzzi, managing at once in Moscow two competing circuses, and with a severe penury of high-level performers to boot, was certainly a hopeless task—and it might have been this situation that led to the state of affairs lamented by Mikhail Bulgakov in his novel.

Williams Truzzi left the management of Moscow’s circuses in 1924 to take over the old Circus Ciniselli in St. Petersburg (which was now Leningrad). Circus Nikitin survived only another two years; it was closed in 1926, and transformed into the Moscow Variety Theater. Ten years later, in 1936, it changed again its name to Theater of Satire. The basic structure of the building erected by Akim Nikitin in 1911 still stands today, and its old circus cupola can be seen behind the bland, unattractive façade that has replaced the Art-Nouveau original designed by B. M. Nilus.

The Bolshoi Circus (1971-present)

In 1964, Leonid Brezhnev succeeded Nikita Khrushchev at the helm of the Supreme Soviet. His long reign, known as the Era of Stagnation, created an economic situation that would trigger the slow disintegration of the Soviet regime, but even so, it witnessed the emergence of the Soviet Circus’s Golden Age. In some ways, Brezhnev had a vested interest in the circus: His troublesome daughter, Galina, married twice into the profession. The first time, with the celebrated antipodist(French: Antipodiste, Russian: Antipod) Foot juggler. Evgeniy Milaev (1910-1983); and the second time with the famous magician Igor Kio, (1944-2006), who was fifteen years her junior—although this latter union was very short-lived (nine days) and shrouded in scandal.

At the end of the 1960s, Brezhnev ordered the construction(French) A temporary circus building, originally made of wood and canvas, and later, of steel elements supporting a canvas top and wooden wall. Also known as a "semi-construction." of a new, ultramodern circus in Moscow, a large building equipped with ground-breaking technical amenities, which would be the flagship of the Soviet Circus. Yakov Belopolsky, the most famous architect of the Brezhnev era and author of many official buildings and monuments, was given the project. He surrounded himself with three other architects, E. Boulikh, S. Feoksitov, and V. Khavin—who were probably more versed into the specificities of theater architecture and its technical requirements than Belopolsky, and perhaps also abler to develop new technical tools specific to the circus.

Located on Lenin Hill (today Sparrows Hill), on Vernadsky Avenue, southwest of central Moscow, the “New Circus” (as it was called, although its official name was Moscow Circus On Lenin Hill), opened its doors April 30, 1971. With 3,300 seats, it is still today the world’s largest indoor circus, yet its technical installations are what make it truly exceptional. Among other amenities, the building includes a rehearsal ring backstage in a space large enough to accommodate big aerial acts; a large stage above the artists’ entrance to the ring, connectable to the ring through a telescopic staircase that comes down electrically from under the stage; the possibility for aerialists to reach their apparatus from the ceiling; and rooms at various temperatures for the keep of the different animal species.The jewel of the crown, however, is the system of interchangeable rings. They are located in a vast basement under the house, around a hydraulic elevator placed at their center, and can be rolled in and brought up at house level as need be. There is a traditional equestrian ring (covered with a special rubber mat, the first that was used in any circus, and which has become standard in Russia); a three-meter-deep water basin, equipped with fountains and underwater lighting; an ice ring; a wooden floor with trapdoors for magicians; and a lighted floor with changeable colors. The system not only allows to quickly adapt the ring to any need, it also allows the installation of cumbersome props on a specific ring while another is in use.

No one was truly surprised indeed when Evgeniy Milaev, was given the management of the New Circus in 1977. Milaev’s reign, which lasted until 1984, was unfortunately tainted by one of the biggest scandals in the history of the Soviet Circus, with corruption at all levels, kickbacks, and even diamond trafficking in which Galina Brezhneva was involved… Leonid Brezhnev had no other choice than to “encourage” Milaev’s resignation. The management was then given to the celebrated perchist Leonid Kostiuk, who had already managed the Circus On Tsvetnoy Boulevard before it was taken over by Yury Nikulin in 1983.

Leonid Kostiuk shepherded the New Circus into the post-communist era and the twenty-first century. Now called the Great Moscow State Circus (Большой Московский Государственный цирк), or Bolshoi Circus in English (Bolshoi means great, or big, in Russian), the jewel of the Soviet Circus had become over the years an oversized, rusty ship difficult to restore and maintain since the quality of construction(French) A temporary circus building, originally made of wood and canvas, and later, of steel elements supporting a canvas top and wooden wall. Also known as a "semi-construction." in the Brezhnev era was wanting at best, and its heavy machinery had been built with non-standardized parts that became increasingly difficult to replace. Financial mismanagement, common in the post-Soviet era, didn’t ease the problem either.

In 2012, however, a change of administrative management at the Bolshoi Circus marked the dawn of a new era, and it came with the beginning of a long-awaited restoration. In 2013, the Ministry of Culture of the Russian Federation began to renew their interest in the circus arts, which led to a major clean up of the Russian circus, starting with the way the many state circus buildings operating in Russia were managed. In the process, the Bolshoi Circus passed under the responsibility of the brothers Edgard and Askold Zapashny, who already managed their own private (and successful) circus company, and are probably the most recognizable circus stars in Russia today—and certainly the most creative.

The Zapashnys modernized at long last the building—physically, as well as in terms of its internal organization. They added new, cutting-edges technologies to the old technology that had made the circus unique in its early years, notably replacing the circular screen at the top of the house by a LED wall substituting for old projections that were obsolete and not used anymore. The very contemporary and innovative productions concocted by Askold Zapashny attract today a new generation of spectators on Vernadsky Avenue. Thus the mighty Bolshoi Circus has entered a bright period of renaissance.

Suggested Reading

- Yury Dmitriev, Мой старый Цирк Бульвар Цветной (My Old Circus, Tsvetnoy Boulevard) (Moscow, Lazur, 2000) — In Russian — ISBN 5-85806-028-5

- Rudolf Evgenievich Slavskiy, Братья Никитины (The Brothers Nikitin) (Mосква, Искусство, 1987) — In Russian.

See Also

- Circuses: Circus Nikulin, Bolshoi Circus