Difference between revisions of "Nouveau Cirque (Paris)"

From Circopedia

(→The Final Years) |

(→The Final Years) |

||

| Line 373: | Line 373: | ||

Béby, Antonet's auguste, was not new to the Nouveau Cirque: he was Aristodemo Frediani, of the legendary jockey act, the Fredianis. Although he had been, with his brothers, an equestrian star of first magnitude, his had always wanted to be a clown and this is what he did as soon as he retired from the family act. Béby had a strong presence in the ring; his silhouette, square and heavy, with a few surrealistic touches in his attire, was naturally comical and he was extremely funny without having to force his effects. His association with Antonet was a perfect match (in the ring at least). Antonet & Béby gave Parisians a good reason to go to the Nouveau Cirque: Debray had finally found his stars! This may have been just a stroke of luck, however, for the uninspired Debray had remained true to himself in his programs: His headliners were fairground thrill acts, and he even hired cage acts from small traveling menageries. | Béby, Antonet's auguste, was not new to the Nouveau Cirque: he was Aristodemo Frediani, of the legendary jockey act, the Fredianis. Although he had been, with his brothers, an equestrian star of first magnitude, his had always wanted to be a clown and this is what he did as soon as he retired from the family act. Béby had a strong presence in the ring; his silhouette, square and heavy, with a few surrealistic touches in his attire, was naturally comical and he was extremely funny without having to force his effects. His association with Antonet was a perfect match (in the ring at least). Antonet & Béby gave Parisians a good reason to go to the Nouveau Cirque: Debray had finally found his stars! This may have been just a stroke of luck, however, for the uninspired Debray had remained true to himself in his programs: His headliners were fairground thrill acts, and he even hired cage acts from small traveling menageries. | ||

| − | Sadly, in spite of the favorable postwar conditions, Debray had proved unable to offer anything really fresh beside his new clowns—but Antonet & Béby couldn't bring back the Nouveau Cirque's old glory by themselves. Then, in 1923, [[Gaston Deprez]] revived the venerable Cirque d'Hiver and restored it to its original splendor. The Nouveau Cirque had now to contend with two very successful circuses, Medrano and the Cirque d'Hiver, as well as with the Cirque de Paris, which had finally managed to create a clientele for itself on the Left Bank. Debray had apparently missed his opportunity, and his cheap brand of circus and variety became completely obsolete in 1924 when the [[Empire Music-Hall Cirque]], whose model was Berlin's famous WinterGarten theater, opened avenue de Wagram, near the Place de l'Étoile, with a brilliant mixture of top variety and circus acts. | + | Sadly, in spite of the favorable postwar conditions, Debray had proved unable to offer anything really fresh beside his new clowns—but Antonet & Béby couldn't bring back the Nouveau Cirque's old glory by themselves. Then, in 1923, [[Gaston Deprez]] revived the venerable Cirque d'Hiver and restored it to its original splendor. The Nouveau Cirque had now to contend with two very successful circuses, Medrano and the Cirque d'Hiver, as well as with the Cirque de Paris, which had finally managed to create a clientele for itself on the Left Bank. Debray had apparently missed his opportunity, and his cheap brand of circus and variety became completely obsolete in 1924 when the [[Empire Music-Hall Cirque]], whose model was Berlin's famous WinterGarten theater, opened avenue de Wagram, near the Place de l'Étoile, with a brilliant mixture of top variety and circus acts. |

| − | The Nouveau Cirque was | + | ===Final Curtain=== |

| + | |||

| + | The Nouveau Cirque was one last time the elegant circus it had once been when the ''Gala de l'Union des Artistes'' was held in its ring for the first time on March 3, 1923 at midnight. Created by the great French actor Max Dearly, it was modeled after the fund-raising gala presented in the same ring ten years earlier by the ''Union des Artistes Lyriques'', but the ''Union des Artistes'', a different benevolent association, encompassed performers of all disciplines, including the theater and the blossoming movies. Playing the role of "Monsieur Loyal," Max Dearly presented a bevy of stars transformed for one night into circus artists, including the unavoidable Mistinguett, the stage and film actresses Jane Marnac, presenting a horse in ''Haute école'', and Maud Loty with a group of trained geese, the celebrated actor Michel Simon as a clown, and the playwright, actor, and Paris's undisputed theater king, Sacha Guitry, doing a magic act. The ''Gala de l'Union'' (as it would be popularly known) became a glamorous Parisian event, held annually first at the Nouveau Cirque, then at the Cirque d'Hiver and a few other locations until 1982. (It was shortly revived from 2010 to 2013, and a last time in 2016.) | ||

Yet, despite the presence in 1924 of [[August Mölker]] with a group of tigers and, the following year, of Petersen with twelve lions from [[Circus Strassburger]]’s menagerie, and notwithstanding the popular Antonet & Béby, too many Parisians had lost interest in the Nouveau Cirque to keep it alive. Not that circus had gone out of favor in the capital: Medrano, the Cirque d’Hiver, the Empire were doing well, and even the Cirque de Paris had now its habitués. But even though it was not easy to make the Nouveau Cirque truly profitable, Charles Debray didn’t have the artistic vision and the creative talents of Raoul Donval, Hippolyte and Jean Houcke, or Mathias Beketov. He may have kept the Nouveau Cirque artificially afloat for a long time, but he couldn’t keep or renew its audiences, unable as he was to give them the quality they expected from this Parisian institution. | Yet, despite the presence in 1924 of [[August Mölker]] with a group of tigers and, the following year, of Petersen with twelve lions from [[Circus Strassburger]]’s menagerie, and notwithstanding the popular Antonet & Béby, too many Parisians had lost interest in the Nouveau Cirque to keep it alive. Not that circus had gone out of favor in the capital: Medrano, the Cirque d’Hiver, the Empire were doing well, and even the Cirque de Paris had now its habitués. But even though it was not easy to make the Nouveau Cirque truly profitable, Charles Debray didn’t have the artistic vision and the creative talents of Raoul Donval, Hippolyte and Jean Houcke, or Mathias Beketov. He may have kept the Nouveau Cirque artificially afloat for a long time, but he couldn’t keep or renew its audiences, unable as he was to give them the quality they expected from this Parisian institution. | ||

Revision as of 20:52, 31 October 2020

By Dominique Jando

Contents

- 1 Les Arènes Nautiques

- 1.1 Joseph Oller

- 1.2 The Panorama of Reischoffen

- 1.3 A Revolutionary Circus

- 1.4 The Nouveau Cirque Opens

- 1.5 Water Pantomimes

- 1.6 Enter Raoul Donval

- 1.7 Paris au Galop

- 1.8 Foottit & Chocolat

- 1.9 Donval’s Circus Stars

- 1.10 Donval’s Revues and Pantomimes

- 1.11 Change of Scenery

- 1.12 Donval’s Final Years

- 1.13 Enter Hippolyte Houcke

- 1.14 Novelty Acts and Traditional Pantomimes

- 1.15 Hail to The New Century!

- 1.16 The Twilight of A Golden Age

- 1.17 Exit Hippolyte Houcke

- 1.18 Mathias Beketov and His Great Russian Circus

- 1.19 Short Interlude: Jean Houcke

- 1.20 Enter Charles Debray

- 1.21 The Pre-War Years: Drifting Away

- 1.22 The War Years

- 1.23 The Final Years

- 1.24 Final Curtain

- 2 Suggested Reading

- 3 Image Gallery

Les Arènes Nautiques

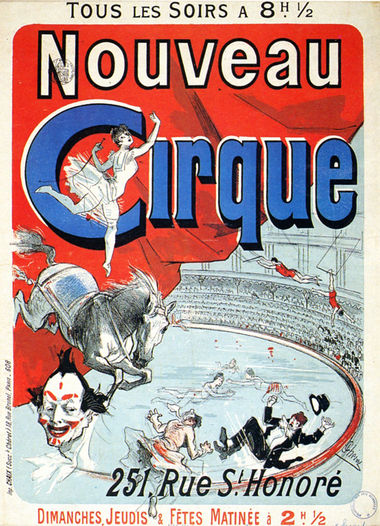

Located from 1886 to 1926 on the rue Saint Honoré in Paris, a chic shopping thoroughfare at a stone’s throw of the Place Vendôme, the Nouveau Cirque was the most elegant and innovative circus of the French capital—and, for that matter, of Europe. For many years, it was the High Society’s circus of choice. Its relatively small size gave it warmth and intimacy (it was sometimes referred to as a "bonbonniere"), but in time, the Nouveau Cirque’s limited capacity made it difficult to manage. It began to lose its prominence before the first World War and proved unable to adapt to the post-war era.

The Nouveau Cirque was built for its times—what is remembered today as the Parisian "Belle Époque" ("Beautiful Era") of which it was one of the jewels. After WWI, Paris entered the Jazz Age. When, in the early 1920s, the venerable Cirque d’Hiver, completely refurbished, returned to the presentation of circus shows after a rather futile hiatus as a movie-house and theater, when the Cirque Medrano was enjoying one of its more lucrative periods, and when the brand-new Empire Music-Hall Cirque opened its doors Avenue de Wagram, the small "bonbonniere" that was the Nouveau Cirque seemed a remnant of another era. It faced a competition it was ill-equipped to fight. Once a revolutionary and trendsetting house whose rich and often glorious life had lasted forty years, the Nouveau Cirque finally called it quits.

Joseph Oller

The Nouveau Cirque was created by Joseph Oller (1839-1922), an imaginative entrepreneur and prolific provider of Parisian amusements. He was born Josep Oller i Roca in Terrassa, in Spanish Catalonia, on February 10, 1839; his parents were Francesc Oller, a fabric(See: Tissu) merchant, and his wife, Teresa, née Roca. The family emigrated to France when Josep was two years old, and the Ollers settled in Paris where Josep, now Joseph, was raised. He eventually returned to Spain to study at the University of Bilbao in the Basque Country, and while there, he discovered cockfighting, which was still very popular in the nineteenth century. His passion for this gory game led him to become a bookmaker—his first entrepreneurial endeavor.

Back to Paris, Oller transferred his bookmaking activities to horse racing. France had gained by then a new Emperor, Napoléon III, whose half-brother, the Duc de Morny, had been influential in the development of horse racing in France and had built the Deauville-La Touques racetrack in 1862. Morny died in 1865, but with his help, Oller had begun to develop the concept of the "pari mutuel" (literally meaning "mutual betting"), an innovative system in which bets are placed in a pool, and the winners share the losers' stakes—after the bookmaker has taken his commission. Oller put his new system to work in 1867; it replaced advantageously fixed-odds betting and made him a rich man indeed. Oller also launched Le Bulletin des Courses, France’s first horse-racing journal.

Then, on July 16, 1870, France declared war to Prussia; Oller, who was thirty-one then, went to London to avoid the conflict. There he began to take an interest in the world of show business—not so much in the theater as in the popular British Music-Hall, which was then blooming. Meanwhile, in September, France suffered a humiliating defeat in Sedan after only one and a half months of fighting, which resulted in the fall of the Second Empire. A new Republic was immediately instituted, and a peace treaty was finally signed in January 1871. The Commune of Paris, a short-lived but violent attempt at a socialist revolution, followed.

After the situation had calmed down, Oller returned to Paris and resumed his bookmaking activities. Unfortunately, in 1875, a French court declared the pari mutuel illicit and Oller was fined and sentenced to fifteen days in jail for illegal gambling. This didn’t discourage him, however; in 1878, he would create the elegant racetrack of Maisons-Laffitte, in the Paris suburbs, and the racetrack of Saint-Germain in 1882. He would eventually be vindicated in 1891 with the creation of the Pari Mutuel Urbain, known as the PMU, an official version of his horse betting system run by the French government! Yet, for the time being, he put to use his new interest in show business.

Oller’s vast bookmaking office was located on the fashionable and theatrical Boulevard des Italiens, on the site of an old variety house, Les Folies Parisiennes; in 1875, after having served his prison term and not to leave his space idle, he transformed it into a new variety theater, Les Folies Oller (which became a legitimate theater three years later). Even though Oller still maintained activities related to horse racing, he was not short of new ideas: In 1885, he opened La Grande Piscine Rochechouart, Paris’s first indoor swimming pool, which was an immediate sensation. During the Second Empire, wealthy Parisians had discovered the pleasures of sea baths (in Deauville notably) and the popular Piscine Rochechouart attracted them en masse. However, it soon became a little too democratic for many of them.

To keep his wealthy clientele happy, Joseph Oller came up with what appears to have been a very original solution: To open a polyvalent space that would be a swimming pool in the summer months, to be transformed into a circus during the rest of the year. Or at least, this is the story as it is usually told; we may wonder, however, if Oller developed this singular idea before or after he found the space on the posh rue Saint-Honoré: Considering the remarkable layout of the locale available to him, we can surmise that he got his circus idea when he saw it—lest he had an incredible stroke of luck in finding a perfect place for a circus project; his initial idea, after all, was to build a swimming pool.

The Panorama of Reischoffen

The space, located at 251 rue Saint-Honoré, had been built to house the "Panorama of Reischoffen" and had opened its doors in November of 1881. Very popular in the nineteenth century, panoramas were large, realistic scenes painted on a giant 360º cyclorama, to which were added tridimensional objects and characters. They generally represented a famous landmark or, more often than not, a famous battle. The panorama exhibited rue Saint-Honoré, titled La Charge des Cuirassés de Reischoffen, depicted a rare French episode of glory in the short-lived Franco-Prussian war of 1870. It spoke to the patriotic fiber of the French people, to whom the defeat of Sedan (and the loss of Alsace, where Reischoffen is located) remained an open wound.

The large rotunda in which the panorama was installed had been erected at the back of what once was the beautiful Salle Valentino, a famous ballroom of the Second Empire that had long lost its luster and had known several unsuccessful transformations. The ensemble that had replaced it had been designed by Charles Garnier (1825-1898), the architect of Paris’s and Monte Carlo’s flamboyant opera houses. (Garnier would build another panorama in 1883, the Panorama Marigny, today’s Théâtre Marigny, in the Jardins des Champs-Élysées.)

Garnier’s rotunda had a diameter of 33 meters (approximately 109 feet), and its cupola culminated at 27 meters (approximately 89 feet) under the lantern. The peripheral wall had a height of 18 meters (about 59 feet). It had no windows, but the cupola had a ribbon of glass running on its periphery, which lighted the panorama. To access his rotunda, Garnier built in the old ballroom’s space a spectacular foyer with a grand staircase, in the Neo-Baroque style that had made him famous. The ensemble was completed by a narrow, yet elegant façade on the rue Saint-Honoré.

Despite its lavish accommodations, the Panorama de Reischoffen was dismantled in 1882 to be taken on tour in the French provinces, where it was exhibited in wooden constructions especially erected for the occasion. With no other panorama to replace it, the Parisian rotunda became practically useless, but Garnier’s elegant foyer was used for various events, from art salons to political meetings. The Panorama Valentino, as it was now known, had become a space for rent—or, eventually, for sale.

As it was, the old panorama’s rotunda and its entrance hall formed an ideal, "ready-to-wear" space to house a circus, especially since all the basic infrastructure was already there! Circus had always been very popular in Paris, and the French capital, with its four active circus buildings (the Cirque des Champs-Élysées, the Cirque d’Hiver, the Cirque Fernando, and the Hippodrome de l’Alma), was Europe’s circus epicenter. No surprise then that the entrepreneurial Joseph Oller decided to combine, in this unexpectedly ideal space of the rue Saint-Honoré, a circus with his swimming pool!

A Revolutionary Circus

The city block on which Oller was to install his Arènes Nautiques ("water arena," as the Nouveau Cirque was originally called at the suggestion of the famous playwright Victorien Sardou) seems to have been predestined for such a project: From 1807 to 1816, it had housed the Fanconis’s second Cirque Olympique, which had been located on the opposite side of the block, rue du Mont-Thabor. Oller, who had obviously never known that long-forgotten circus, had no apparent reason to have chosen his locale by reason of the block’s circus history, as it has sometimes been said. It was just an auspicious coincidence: His choice had been indeed dictated by more prosaic reasons.

The former panorama came with an elegant façade, a majestic entrance hall and a spectacular foyer that didn’t need any significant alterations. The big rotunda that was to accommodate the circus itself and its swimming pool was another matter: It was just a huge empty shell that had to be entirely refurbished, and whose ground had to be dug to install a water basin. Annexes had also to be built to accommodate stables, dressing rooms and, as we shall see, an important machinery. Oller entrusted the project to Gustave Gridaine (1835-?), the architect who had designed Paris’s Cirque Fernando, and Aimé Sauffroy (1840-1907), a pre-Art-Nouveau architect fond of metallic structures, who had designed the very innovative headquarters of the Parisian daily Le Figaro, rue Drouot, in 1874.

To accommodate the use of the place as both a circus and a swimming pool, Gridaine and Sauffroy worked with Louis Solignac (1858-1902), the engineer who had conceived the technical features of the Piscine Rochechouart. Together, they came up with quite an imaginative plan: The six rows of seats directly surrounding the ring were installed on a metallic structure built over the basin. The seats and their supporting structure could be removed in the summer to reveal the full size of the swimming pool, which had a total diameter of 25 meters (about 82.5 feet) and a depth of three meters (10 feet).

At the center of this removable seating system, the circus ring, which had the traditional diameter of 13.5 meters, had a wooden slatted floor standing on a metallic structure supported in its center by a hydraulic column that could lower the ring below water level; during the operation (which took about six minutes), the water rushed through the floor openings. This ingenious contraption was conceived by Léon Edoux (1827-1910) the engineer and industrialist who had developed the first French ascenseurs (elevators)—with which he would later equip the Eiffel Tower between its second and third floors. (Installed in 1889, Edoux’s original elevators on the Eiffel Tower remained in service until 1983!).

Beside its use to lower the ring floor when the swimming pool went into use, Edoux’s system also allowed to transform the ring quickly into a water basin when the building was used as a circus—thus enabling the presentation of water spectacles, which would be the Nouveau Cirque’s most popular attraction(Russian) A circus act that can occupy up to the entire second half of a circus performance.. This revolutionary concept presented a problem however: Circus rings were traditionally covered with soil and sawdust to allow equestrian presentations, which were still an essential part of the circus performance. The architects found a novel solution: They covered the ring with a thick, removable carpet made of woven esparto fibers. The carpet alone weighted two metric tons (about 4,400 pounds); the total weight of the ring floor, when covered, scaled at thirty metric tons, but Edoux’s system was built to manage it.

All this was indeed state-of-the art technology at the time, but this was not the extent of the Nouveau Cirque’s innovations. The entire building was equipped with electric light, which was still a rarity then: The electrification of Paris had just begun in 1882, and the first sections of its electrical network will appear only in 1888. Solignac had to install two powerful generators—which generated not only the necessary power, but also complaints from the circus’s neighbors… (Yet, the building was still equipped with gas lighting in case of electrical failure: Apparently, electrical power was not deemed entirely reliable.) Solignac also designed a system to keep the water temperature in the basin at 25º C (77º F), and the circus and its annexes were outfitted with hot-air heating.

As for the house, its ring, as mentioned before, was surrounded by six rows of individual armchairs with folding seats, a novelty that had just been introduced by the Théâtre du Vaudeville on the Boulevard des Capucines. Behind them was a circle of fifty-six comfortable theater boxes, accommodating five persons each. Above the boxes was a vast promenoir (standing room gallery), with a series of bars scattered on its periphery. This gave a total of only 870 seats, the rest of the patrons standing in the promenoir. The circus was nonetheless advertised as able to accommodate 3,000 spectators, which would have implied an unlikely crowd of more than 2,000 standing in the gallery! The scarcity of actual seats will eventually prove a financial handicap and, later, the entire periphery of the promenoir was outfitted with two additional rows of seats.

The house was decorated in the Neo-Baroque style of Garnier’s foyer with gilded ornaments by Etienne Cornellier (1837-1902), floral decorations by the great specialist of the genre, Eugène Petit (1839-1886), and eleven frescoes depicting scenes of the Roman circus by Jules-Élie Delaunay (1828-1891), a respected artist whose painted panels can still be seen in the Octogonal Salon at the Paris Opéra. The orchestra was perched on a balcony high over the promenoir, above the ring entrance. The entire decorating scheme gave a feeling of warmth and luxury, and the small size of the house (thirty-three meters in diameter, compared to the forty-two meters of the Cirque d’Hiver) added a sense of intimacy.

The all-important annex was built in the courtyard adjacent to the rotunda, expanding the old Panorama’s original extension. It included stables for twenty horses, spaces for the generators and other machinery, and, on the second floor, offices and dressing rooms. The courtyard had long been connected to the rue Saint-Honoré by an alley that opened on the street, a few yards from the circus’s façade. This alley now provided access to the stables, the stage door and a side entrance to the circus.

The Nouveau Cirque Opens

The Nouveau Cirque (the title Oller chose for the circus when it was not used as a swimming pool—and the sole name under which it would subsequently be known) opened its doors on Friday, February 12, 1886. The Tout-Paris of the arts and the racing world was in attendance. The régisseur(French) The stage (or ring) manager—and sometimes Ringmaster—in a French circus. (See also: Monsieur Loyal) général (a position which, in Parisian circuses, was a mixture of artistic, personnel, performance, and equestrian director) was Léopold Loyal (1835-1889), from the prolific French circus dynasty that has provided so many régisseurs to Parisian circuses that a Monsieur Loyal(French) The régisseur or presenter of the show in a French circus. So called because of the many members of the Loyal family who occupied this position brilliantly in Parisian circuses. is today the French term that designates a ringmaster(American, English) The name given today to the old position of Equestrian Director, and by extension, to the presenter of the show..

A popular equestrian and circus director who had already served as régisseur(French) The stage (or ring) manager—and sometimes Ringmaster—in a French circus. (See also: Monsieur Loyal) in Louis Dejean’s Parisian circuses, Léopold Loyal was "tall, large, even ventripotent like a maître d’hôtel, but decorative to a supreme degree, and he held his whip like a Roman emperor his scepter"—according to Georges Strehly in his book L’Acrobatie et les Acrobates (1903). Loyal brought with him his brothers, his sons, and an important roster of artists that, on the opening night, circus critics thought a little uninspiring—but the celebrated clown Billy Hayden saved the evening with his English-accented verbal humor and his trained pig.

Indeed, not everything went well on this first night: The horses, not used to working on an esparto mat, were particularly unruly, but the horse-savvy audience took it in stride. This was of no consequence compared to the fantastic spectacle offered by the removal of the mat and the extraordinary vision of the ring being transformed into a water basin—in which scantily-clad naiads made graceful evolutions to boot! In its review of the event, the very influential Journal des Débats waxed enthusiastic, calling the Nouveau Cirque "the eighth wonder of the world." Oller’s wealthy patrons were also impressed by the new circus’s magnificence and its comfort, and soon its boxes were sold out for the season. The Nouveau Cirque was an unmitigated success, and here to stay.

Its company of performers was quickly reinforced, notably with the arrival of a talented young clownGeneric term for all clowns and augustes. '''Specific:''' In Europe, the elegant, whiteface character who plays the role of the straight man to the Auguste in a clown team., George Foottit, whose parody of a ballerina on horseback was a huge hit. Foottit will quickly become the Nouveau Cirque’s star clownGeneric term for all clowns and augustes. '''Specific:''' In Europe, the elegant, whiteface character who plays the role of the straight man to the Auguste in a clown team.. The water basin, which had proved to be the circus’s main attraction(Russian) A circus act that can occupy up to the entire second half of a circus performance., welcomed the dives and evolutions of a professional naiad, Agnes Beckwith, "The Greatest Lady Swimmer of the World," who, claimed her advertising, had performed for the Prince and Princess of Wales. The Princess was certainly mentioned for wants of propriety—since performing for the notoriously dissipated Prince of Wales (the future Edward VII) in a bathing suit was not necessarily an accomplishment to publicize!

For the summer break, the building switched to its original purpose, the Arènes Nautiques, Joseph Oller’s summer indoor swimming pool. It was a complete fiasco! Oller had not taken into account that, in the summer, wealthy Parisians preferred to leave the capital and go to elegant seaside resorts such as Deauville, Biarritz, Nice and Monte Carlo, where casinos and racetracks added to (and often overcame) the healthy pleasures of the beach. Whether advertised as Arènes Nautiques or Bains du Nouveau Cirque ("Nouveau Cirque’s Baths"), the swimming pool never took off. It would be soon abandoned—but not the circus, a lucky second thought that was paying back Oller’s investment.

Water Pantomimes

The 1886-87 season opened with the elephant act of Samuel Lockhart, which proved, if need be, that the ring support was sturdy enough to support their evolutions. Star equestriennes Adelina Price and Elvira Guerra came to reinforce the equestrian department, Foottit consolidated his position as principal clownGeneric term for all clowns and augustes. '''Specific:''' In Europe, the elegant, whiteface character who plays the role of the straight man to the Auguste in a clown team., The Hanlon-Voltas confirmed that the Nouveau Cirque could accommodate a big flying actAny aerial act in which an acrobat is propelled in the air from one point to another., and the Johnson Swimmers (male and female) exhibited their graceful bodies in the basin. But the event that was to define the Nouveau Cirque occurred in December 1886: La Grenouillère was the first of a long string of water pantomimes.

This first water pantomimeA circus play, not necessarily mute, with a dramatic story-line (a regular feature in 18th and 19th century circus performances)., whose paper-thin storyline had been written by Raoul Donval (who was going to be intimately associated with the Nouveau Cirque three years later) and Pierre Delcourt (1852-1931), with a musical score by Laurent Grillet (1851-1901), the Nouveau Cirque’s musical director, was inspired by the popular boating establishment-cum-spa and floating café of the same name. Easily accessible by train from Paris, La Grenouillère was located on the Seine river, near Bougival, and had been once visited by Napoléon III and his family, which made it a fashionable middle-class destination. Painted by Claude Monet and Auguste Renoir and the setting of a short story by Guy de Maupassant, its sole name evoked fun and water frolics—which was just what the Nouveau Cirque offered its spectators, with lovely naiads having a great time and boisterous clowns falling into the water with a big splash.

Not very refined perhaps, but it was a huge success. If the Nouveau Cirque’s pantomimes that followed would remain as simplistic and infantile as La Grenouillère (even though they were created to entertain a mostly adult audience), they were nonetheless lavishly produced, with elaborate sets, intricate staging and amazing special effects that would make them visually spectacular. They provided the kind of spectacle that prompted Jean Cocteau to reminisce, in 1935, about the then-defunct Nouveau Cirque: "The program’s highlight was the water pantomimeA circus play, not necessarily mute, with a dramatic story-line (a regular feature in 18th and 19th century circus performances).. The surge of the water leaves me with poignant memories. No trickAny specific exercise in a circus act., no gag of the cinematograph will ever replace this wonder."

Another pantomimeA circus play, not necessarily mute, with a dramatic story-line (a regular feature in 18th and 19th century circus performances)., authored by Henri Agoust (1840-1901) and titled La Foire de Séville ("The Fair at Seville") followed in March 1887, but this one, which included songs and dances and a large dose of comedy including a bullfight parody, didn’t use the swimming pool and remained dry. Henri Agoust, who had been appointed régisseur(French) The stage (or ring) manager—and sometimes Ringmaster—in a French circus. (See also: Monsieur Loyal) in charge of the spectacles and pantomimes, was a former juggler with an extensive training in ballet and mime; his wife, Rosita Zanfretta, who came from an old circus family, had made a name for herself on the flying trapezeAerial act in which an acrobat is propelled from a trapeze to a catcher, or to another trapeze. (See also: Short-distance Flying Trapeze) as Azella, "The Female Léotard." Agoust, had long been associated with the famous acrobats and pantomimists Hanlon Brothers and had authored and choreographed several ballets.

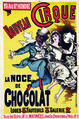

Le clown Tony Grice led the pièce de résistance of La Foire de Séville, its bullfight parody. A well-known and popular clownGeneric term for all clowns and augustes. '''Specific:''' In Europe, the elegant, whiteface character who plays the role of the straight man to the Auguste in a clown team., Grice had joined the Nouveau Cirque the previous year with his young black assistant, a former Cuban slave he had found in Spain and nicknamed Chocolat (meaning chocolate)—an unimaginative racial slur that sounded funny at the time. Chocolat will soon become a pillar of the Nouveau Cirque and he will write with George Foottit an important page of French circus and clown history.

The company went on a provincial tour during the summer break and, for the opening of the 1887-88 season, the Nouveau Cirque reprised La Grenouillère, which still packed the house, and in December, launched a new water pantomimeA circus play, not necessarily mute, with a dramatic story-line (a regular feature in 18th and 19th century circus performances)., Le Carnaval de Venise ("Carnival in Venice"), with the participation of a group of Neapolitan singers, a few gondolas, dancers and naiads, and the inevitable fall of the clowns into the water—all that to the Italian tunes of Lucien Grillet’s band of forty musicians. As usual, the pantomimeA circus play, not necessarily mute, with a dramatic story-line (a regular feature in 18th and 19th century circus performances). occupied the third part of a show in three parts, in which Tony Grice and George Foottit still battled for the position of star clownGeneric term for all clowns and augustes. '''Specific:''' In Europe, the elegant, whiteface character who plays the role of the straight man to the Auguste in a clown team.—with a growing advantage for Foottit. Le Carnaval de Venise was another triumph that ran until March 1888.

It was immediately followed by yet another water spectacle, La Noce de Chocolat ("Chocolat’s Wedding"), which was to become the Nouveau Cirque’s most famous pantomimeA circus play, not necessarily mute, with a dramatic story-line (a regular feature in 18th and 19th century circus performances). and will be reprised several times. Staged (and probably conceived) by Henri Agoust, it told the story of a wedding in a riverside guinguette (tavern), such as they could be found around Paris on the banks of the Seine and Marne rivers. The groom was black, and his wife-to-be was a charming white maiden… The newlyweds were happily celebrating, with music, songs, dances and gags, when a group of revelers crashed the party, intent on kidnapping the bride, perhaps to "protect" her from a black husband… A brawl ensued and eventually, true to tradition, everybody fell into the water…

The groom was played by Chocolat, whose appearance in this piece was his first as a featured performer (up to then, he had just been an occasional comic character and a sidekick for Tony Grice). Chocolat was a good dancer and he was very nimble physically. Since he was black, the audience of the time expected him to be ridiculed, but Chocolat had a true comic nature, which George Foottit and his colleagues had indeed already noticed, and he had an engaging personality that pleased the audience. Having no formal training in dance, acrobatics or comedy, he was still a little rough around the edges, but he was what is called in show business "a natural."

La Noce de Chocolat was the Nouveau Cirque’s most successful pantomimeA circus play, not necessarily mute, with a dramatic story-line (a regular feature in 18th and 19th century circus performances). so far. The rest of the program also featured "Caviar," the riding bear, which was another sensation, and Le Figaro enthusiastically noted: "With Caviar and La Noce de Chocolat, there is enough to make all Paris run to the Nouveau Cirque for months to come…" And indeed, so did Paris until the end of the season.

On the 1st of October 1888, the new season began with a "dry" pantomimeA circus play, not necessarily mute, with a dramatic story-line (a regular feature in 18th and 19th century circus performances)., Lulu, written by the well-known journalist and author of erotic novels, Félicien Champsaur (1858-1934). Staged by Henri Agoust, this poetic fantasy featured Mlle. Massoni playing Lulu, a clownesse who had lost her heart (literally), with Agoust as an old, pedantic professor and Foottit as a dandy named Harlequin. A bevy of pretty girls in skimpy costumes completed the cast. It was quite innocent but, thanks to Champsaur’s naughty reputation, it made Parisians run again to the Nouveau Cirque. (In 1900, Champsaur will revive Lulu in a very successful novel titled Lulu, Roman Clownesque.)

The water basin was not forgotten, though: It was used to stage a "combat naval" (naval battle) with miniature warships. Then, in December, the pool was the setting for a new water pantomimeA circus play, not necessarily mute, with a dramatic story-line (a regular feature in 18th and 19th century circus performances)., still staged by Agoust, L’île des Singes ("Monkeys' Island). Chocolat starred again in this one, which he had inspired: It featured the music and dances of Cuban slaves in a story set in a Caribbean island where a group of mischievous monkeys created mayhem and eventually manhandled the poor Chocolat—the hapless cook of the plantation’s owner, played by Foottit. Snapping his whip, Foottit restored order, which resulted in many comic situations and, as usual, everybody falling into the water…

Enter Raoul Donval

This was the last pantomimeA circus play, not necessarily mute, with a dramatic story-line (a regular feature in 18th and 19th century circus performances). staged under Joseph Oller’s reign. He resigned his directorial position at the end of the year to pursue other projects, which would include the creation of the Bal du Moulin-Rouge and the Montagnes Russes, a scenic roller coaster he erected on the Boulevard des Capucines and on the site of which he subsequently built the Olympia theatre, Paris’s first British-style Music-Hall (which is still extent). Leopold Loyal took over the Nouveau Cirque’s interim management, while the circus’s shareholders looked for a successor to Oller. They had to act quickly: Paris’s Exposition Universelle (World’s Fair) was due to open its doors in May 1889, and the Nouveau Cirque had to go full steam ahead to take good advantage of the millions of visitors that would flock to the capital.

Léopold Loyal reprised two Nouveau Cirque’s proven successes, La Noce de Chocolat in February, and La Foire de Séville in March, and Parisians discovered a very talented and, to their eyes, exotic Japanese tight-wire dancer nicknamed "Little All Right" (his real name was Umekichi Hamaikari), whom Richard Risley Carlisle, the famous "Professor" Risley who originated the Risley actAct performed by Icarists, in which one acrobat, lying on his back, juggles another acrobat with his feet. (Named after Richard Risley Carlisle, who developed this type of act.), had brought back from his Japanese tours. Loyal’s interim management came to an end on June 9, 1889, when Oller’s successor, Raoul Donval (1852-1898), was put at the helm of the Nouveau Cirque; he would manage it with great success for the next eight years—during which the circus of the rue Saint-Honoré entered its golden age.

The son of a gendarme, Raoul Donval was born Arthur Théobald Gilloreau on February 19, 1852 in Noailles, a small town in the Oise department, near Paris. He began his professional life as a telegrapher for the Chemins de Fer du Nord (a railway company), but he was attracted by the stage and decided to become an actor. In 1877, at age twenty-five, he debuted at the Théâtre de l’Athénée in Paris in the small role of… Césarius, a circus director, in Richard O’Monroy’s one-act comedy, On demande un homme fort ("Strongman Wanted"). That same year, he had married the comic singer Thérésa (née Emma Valladon, 1837-1913), who suggested that he change his name to the hammier Donval, made of the inverted first and last syllabi of her legal name (Valladon).

Although he worked regularly, Donval’s career as an actor was a little lackluster, but, blessed by a good business sense, he organized theatrical tours and then took over the management of the Alcazar d’Hiver, a famous Parisian "café concert," most probably with his wife’s help: She was the Alcazar’s main drawing card. Nicknamed "La diva du caf’ conc’," Thérésa became France’s first true international superstar (before Sarah Bernhardt and Yvette Guilbert); Donval organized for her international tours that took her as far as St. Petersburg in Russia. Thérésa won quite a fortune and retired in 1893. She divorced Donval three years later.

In the summertime, Raoul Donval managed the Casino of Saint-Valery-en-Caux, a small seaside resort on the cost of Normandy. Donval had been recommended by Edmond Blanc, a horse breeder and politician, and his brother Camille, who was the owner of the Casino of Monte Carlo (created by their father, François Blanc); the Blancs were part of Oller’s business circle and probably shareholders of the Nouveau Cirque. Raoul Donval was already familiar with the Parisian circus, for which he had written La Grenouillère, and he was used to dealing with circus and variety artists; to the Blanc brothers, his successful tenure at the helm of the casino of Saint-Valery-en-Caux was a plus that appealed to them: He had the perfect credentials for the job! Donval left the management of the Alcazar to his wife and moved rue Saint-Honoré.

One month before Donval’s arrival, Geronimo Medrano, the Cirque Fernando’s star clown and its Régisseur Général, had left the circus that had made him famous (Fernando was in dire financial troubles) to join the Nouveau Cirque’s company. Medrano was popular among performers and had amply proven his competence as Fernando’s régisseur(French) The stage (or ring) manager—and sometimes Ringmaster—in a French circus. (See also: Monsieur Loyal); Donval gave him Léopold Loyal’s former position: In bad health, Loyal had decided to retire; he would die a few months later, on December 19, 1889. His son Paul succeeded him as Equestrian Director, and it seems that Henri Agoust left the Nouveau Cirque at that time.

Although Medrano had been an acrobat and aerialistAny acrobat working above the ring on an aerial equipment such as trapeze, Roman Rings, Spanish web, etc. and was indeed quite competent with horses, the Nouveau Cirque’s clowns saw the fact that he was one of them as a boon. Furthermore, they had a strong ally in the person of Donval himself, a bon vivant with a healthy sense of humor, who was interested in clown comedy: In 1896, he would publish a precious little book, Pantomimes du Vieux Cirque, a repertory of comic scenes and clown entrées that had been performed in the old Cirque Olympique on the Boulevard du Temple. Under Donval’s reign, clowns such as Pierantoni & Saltamontes, Medrano and, most importantly, Foottit and Chocolat, will become the Nouveau Cirque’s main drawing cards—along with the water basin into which they occasionally fell, that is.

Paris au Galop

To take full advantage of the flood of tourists that were expected to visit the Exposition Universelle, known as the "Expo," Donval kept the circus open for the summer and added a few matinees on its schedule. He also had two rows of seats installed on the periphery of the promenoir, which became the balcon (balcony) and increased the house seating capacity to 1,170 seats. Expo aside, such changes made the circus more profitable.

The theme of the Parisian Expo was the extraordinary accomplishments of the new industrial age—spectacularly illustrated by Gustave Eiffel’s stupendous 300-meter tower. With its amazing sinking ring and its revolutionary technology, the Nouveau Cirque perfectly fitted the picture—not to mention that it also provided good entertainment. Donval reprised the Nouveau Cirque’s first success, La Grenouillère, his own water pantomimeA circus play, not necessarily mute, with a dramatic story-line (a regular feature in 18th and 19th century circus performances)., which was to remain his circus’s main attraction(Russian) A circus act that can occupy up to the entire second half of a circus performance. (and provided him with royalties) until the end of the Expo, which closed on October 31.

In a mere six months, the Expo had catered to more than 32,000,000 visitors, many of whom had come from the French provinces and foreign countries. Paris had enjoyed a summer of celebration and fun that, suddenly, had come to a halt! After their initial hangover, Parisians began to suffer from Expo withdrawal. Donval, feeling the pulse of the city, asked two well-known librettists, Surtac and Alévy (Gabriel Astruc, 1864-1938, and Armand Lévy, 1859-1935) to write a revue for the Nouveau Cirque that would reflect on the main events of the year—which was the original purpose of revues, before they slowly morphed into meaningless extravaganzas in the twentieth century.

Surtac and Alévy had scored a hit at the Cirque Fernando at the beginning of the year with a revue they had written for Geronimo Medrano, En selle pour la revue—and it is probably Medrano who, as its Régisseur Général, was actually at the origin of the Nouveau Cirque’s revue: Until Fernando’s En selle pour la revue, which had been written and produced at Medrano’s request, revues had been exclusively a stage affair. Paris au Galop opened at the Nouveau Cirque on November 13, 1889. It was a revue équestre et nautique (equestrian and nautical revue) which was staged between the four pillars of an Eiffel Tower made out of an elaborate web of ropes.

Paris au Galop was yet another triumph, praised by the critics and loved by the audience; it perfectly spoke to the Parisians’ nostalgia of their defunct Expo. In December 1889, the famous theater critic Jules Lemaître noted in his Impressions de Théâtre: "Such is the mysterious superiority of the reflect of the moon and the memories of love over love and the moon themselves and of the feigned image over reality, — when the floor let the water come through an sank little by little; when the fragile tower of the Nouveau-Cirque began to glare in the red aura of Bengal lights; when finally a beam of colored light came down from the cupola on the meagre water squirt in the center to replicate the 'fontaines lumineuses' [illuminated fountains], we all saw again the spectacles of this summer and I believe we were happier and more dazzled than we had ever been during the most fantastic evenings of the Champs-de-Mars."

Yet, pantomimes and revues were not the only things that brought the audience to the Nouveau Cirque. For instance, the lions (and a Great Dane) of Carl Hagenbeck presented by Darling (whose real name was Eduard Deyerling) were featured in the same program as Paris au Galop, to which they were an added sensation. Darling’s lions would return several times to the Nouveau Cirque. They were presented in a very ornate cage that was fixed on the ring’s banquette(French. U.S.: Ring Curb. Russian: Barrier) The circular barrier that defines the ring—so called because it is traditionally large enough for someone to sit on it. (ring curb(American. French: Banquette. Russian: Barrier) The circular barrier that defines the ring, and separates it from the audience.), with two large grille-panels that opened at the ring entrance and protected the spectators on each side while allowing the lions to enter through the curtain (as they often do, today, in the Russian circus); the panels also allowed to bring in the Roman chariot on which Darling rode, pulled by his lions. All that was spectacular, but the artists who appeared in the same part of the program as Darling had to perform in a cage…

Foottit & Chocolat

Its clowns also amply contributed to the Nouveau Cirque’s success: George Foottit, Tony Grice, "Boum-Boum" Medrano, Alexandre Pierantoni and his partner, the Spanish clown Saltamontes and, of course, Chocolat, among others. Foottit, who was, like everyone else, aware of Chocolat’s potential had asked Donval to hire him independently of Tony Grice, of whom Chocolat had been the assistant in the ring and the servant in private life. Hence, Chocolat truly became a free man and a clown in his own right. As he had done before, he appeared as a partner to other clowns, among whom Pierantoni, Medrano and Foottit. He would eventually write clown history with Foottit, but this history had already begun at the Nouveau Cirque with another clown duet, Pierantoni and Saltamontes.

Pierantoni and Saltmaontes, who had never worked together before their engagement at the Nouveau Cirque, had been suggested to Raoul Donval by Félix Gontard, the first French "augusteIn a classic European clown team, the comic, red-nosed character, as opposed to the elegant, whiteface Clown.," who had seen them work, independently of each other, in Portugal. Pierantoni and Saltamontes began to work occasionally together rue Saint-Honoré, as it was the custom with clowns, but their partnership generated a special chemistry the audience loved: They perfectly complemented each other. Encouraged by Donval and Medrano, they eventually went on to form a distinctive clown duet and create their own repertoire, the first clowns ever to do so—as surprising as it may seem today (at least to an European audience).

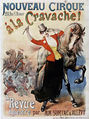

Then, in 1890, the Nouveau Cirque presented another revue by Surtac and Alévy, À la Cravache ("To The Whip") in which Foottit made the headlines. The great tragedienne Sarah Bernhardt was playing Cléopâtre (Cleopatra) in Victorien Sardou’s eponymous play; as usual, she obtained an immense success, but her then-conventional and much admired overacting invited easy parody—especially the tragic grandiloquence of Cleopatra’s lengthy death scene—and Foottit jumped at the opportunity. His parody was hilarious: Foottit’s Sarah-Cleopatra, replete with opulent red mane, bejeweled dress, and her fatal rubber snake, died endlessly before finally resurrecting. Foottit's piece, in which Chocolat played a slave and Saltamontes was Mark Antony, quickly became the talk of the town.

The tragedienne’s coterie was outraged—notably her author, Victorien Sardou—which turned Foottit’s parody into a mini Parisian scandal. Eventually, Bernhardt decided to judge by herself, and went to see Foottit perform. In every respect the diva, she and her entourage made a grand entrance that practically stopped the show just a few moments before Foottit’s turn. As Foottit entered the ring, the house froze when Madame Sarah bellowed out a peremptory "Clown, fais-moi rire!" ("Clown, make me laugh!"), which would have been enough to paralyze any comedian, regardless of his talent. Yet Foottit didn’t flinch and went on with his lampoon, and Madame Sarah laughed heartily. Not only the scandal melted away, but it had been excellent publicity for the Nouveau Cirque.

It is around that time that Foottit began to work regularly with Chocolat (although Chocolat will continue working occasionally with other partners). There was indeed an exceptional chemistry between them, albeit different from that of Pierantoni and Salamontes: Whereas the latter exhibited a friendly and warm rapport in the ring, Foottit and Chocolat had an antagonistic relationship, in which Foottit was an authoritarian boss to the hapless Chocolat—although, as Louis Lumière’s early films of the duo demonstrate, either one could be duped by the other.

What was especially interesting, however, is that the duet's characters were clearly defined: Foottit, a whiteface clown donning the customary costume that came from the medieval jester tradition, was the leader of the duet; Chocolat was an "augusteIn a classic European clown team, the comic, red-nosed character, as opposed to the elegant, whiteface Clown.," an everyday man without the skills and artificial trappings of the clownGeneric term for all clowns and augustes. '''Specific:''' In Europe, the elegant, whiteface character who plays the role of the straight man to the Auguste in a clown team., and whose humor derived from his difficulty to adapt to the society’s established foibles. The duo’s characters and roles were well delineated by their rapport in the ring as well as their physical appearances. The contrast of a white face and a black one added to the distinction.

Foottit and Chocolat had originated the traditional duo formed by a clown and an augusteIn a classic European clown team, the comic, red-nosed character, as opposed to the elegant, whiteface Clown., which will be emulated afterwards by countless duos of the same type. But their considerable success also came from the sketches they presented. These were for the most part old clown entrées that had been performed for times immemorial—but since Chocolat was too unruly to be trusted in improvised pieces, Foottit gave these entrées a solid structure, with a beginning, a middle and an end to which the partners had to stick. In the process, these entrées became much better pieces of comedy, gaining a coherent logic of their own and adapted to the personalities of the clowns who played them. Foottit & Chocolat had redefined modern clown comedy.

Donval’s Circus Stars

The Nouveau Cirque’s audiences couldn’t tire of watching Foottit & Chocolat performing together: They quickly became the toast of Paris—especially Chocolat, who had joined the bohemian crowd of Montmartre and was immortalized by Toulouse-Lautrec. But they were not the only stars that appeared at the Nouveau Cirque outside of its pantomimes and revues. The original nucleus of the Nouveau Cirque’s audience had been largely formed by Oller’s acquaintances from the racing world, including the members of the Jockey Club, who had a great interest in horsemanship in all its facets. As a matter of fact, everybody at the time had a vested interest in horses, which were still indispensable to daily life, from agriculture to transport, war to leisure. And to see horses at their best, one went to the circus. The Nouveau Cirque, like, before it, the venerable Cirque des Champs-Élysées, was the true horse aficionados’ rendezvous of choice.

Under Donval’s tenure, some of the equestrian arts’ greatest names were featured at the Nouveau Cirque: The superb Elvira Guerra; the stunning Baronne de Rahden, whose horse left the ring walking "en cabrade" on his hind legs with the Baroness, riding sidesaddle, lying head down on her horse’s croup (originated by Jenny de Rahden, this "cabré renversé" became, years later, Paulina Schumann’s trademark); Isabelle Chinon, one of the rare women to ride in haute-école(French) A display of equestrian dressage by a rider mounting a horse and leading it into classic moves and steps. (See also: High School) sitting astride her horse, like her male counterparts; the incomparable James Fillis, who had just authored the horseman’s new bible, Principes de dressage et d’équitation (1890), and attracted cavalry officers en masse rue Saint-Honoré; and the extremely talented and fearless equestrienneA female equestrian, or horse trainer, horse presenter, or acrobat on horseback. Blanche Allarty, the pupil and protégée of the master horseman Ernest Molier, whose famous "Cirque d’amateurs" (amateur circus) in his Parisian mansion’s courtyard, rue de Bénouville, drew the same fancy crowd as the Nouveau Cirque.

There were also major stars from other circus disciplines: The famous jugglers Severus Schaeffer, who spiced his act with acrobatics, and Paul Cinquevalli, the first true international juggling star; the Ancillotti Toupe, "Premiers vélocipédistes du monde," performing extraordinary acrobatic and balancing exercises on their penny-farthings and unicycles; Edmond Rainat, indisputably the greatest specialist of the bar-to-barA flying trapeze act in which flyers leap from a trapeze to another, instead of from a trapeze to a catcher as is most commonly seen today. flying trapezeAerial act in which an acrobat is propelled from a trapeze to a catcher, or to another trapeze. (See also: Short-distance Flying Trapeze) (without catcherIn an acrobatic or a flying act, the person whose role is to catch acrobats that have been propelled in the air.) and his partners, and, in the same specialty, the troupe of Raoul Monbar, Rainat’s main competition; Miss Athleta (née van Huffelen), the amazing Belgian woman who could bring any strongman to shame; the Romanian troupes Popescu and Luppu in their thrilling acrobatics on the horizontal bars—among scores of other top talents.

Donval’s Revues and Pantomimes

Yet, pantomimes and revues remained the Nouveau Cirque’s chief drawing card, and a long string of them, old and new, were produced under Donval’s management—most of them written by well-known authors and librettists. One particularly distinguished itself: it featured the famous "diseuse" Yvette Guilbert (1865-1944), the great star of the variety stage (and one of Toulouse-Lautrec’s favorite subjects), who played the part of "La chanteuse" in Garden-Party (1891), a humoristic piece written by the novelist Pierre Delcourt (1852-1931) and the librettist Victor Meuzy, with music by the Nouveau Cirque’s prolific musical director, Laurent Grillet. Guilbert was a hot ticket, and she packed the house.

1891 also saw Gribouille, a "pantomimeA circus play, not necessarily mute, with a dramatic story-line (a regular feature in 18th and 19th century circus performances). villageoise à grand spectacle" by Bid and Talbert, and Le Roi Dagobert ("King Dagobert,"), which included a spectacular deer hunting scene which ended, as expected, into the swimming pool. (King Dagobert is mostly remembered in French folklore for being so distracted that he put his trousers the wrong way around…) Surtac and Alévy returned in January 1892 with a new revue, À fond de train ("At Full Speed"), which featured parodies by the Nouveau Cirque’s star clowns, many horses, the water basin, and a bevy of pretty girls. Don Quichotte, a "Bouffonnerie équestre à grand spectacle" ("Equestrian buffoonery spectacular") followed, before a reprise(French) Short piece performed by clowns between acts during prop changes or equipment rigging. (See also: Carpet Clown) of Le Roi Dagobert, which ended the season.

In October 1892, the new season began with a reprise(French) Short piece performed by clowns between acts during prop changes or equipment rigging. (See also: Carpet Clown) of Gribouille before the presentation of Raoul Donval’s latest opus, a "fantaisie japonaise et nautique à grand spectacle" ("Japanese and nautical fantasy spectacular") in two tableaus with a musical score by Laurent Grillet, titled Papa Chrysanthème—which was a parody of Pierre Loti’s 1887 stereotypical novel, Madame Chrysanthème. Instead of a big splash into the water basin, the second tableau featured a "waterlilies ballet" with a group of eye-catching naiads. Papa Chrysanthème ran well into 1893.

In April, Foottit was the hero of the "pantomimeA circus play, not necessarily mute, with a dramatic story-line (a regular feature in 18th and 19th century circus performances). à grand spectacle" Pierrot Soldat, a classic pantomimeA circus play, not necessarily mute, with a dramatic story-line (a regular feature in 18th and 19th century circus performances). revisited for the occasion, in which Pierrot is an unfortunate conscript trying to adapt to military life, where his superiors’ orders, when taken literally, result in hilarious situations. It was an elongated version of what would later become a classic clown entrée(French) Clown piece with a dramatic structure, generally in the form of a short story or scene., Le service militaire (The Military Service).

The last offering of the 1892-93 season was a "folie nautique" (nautical folly) titled La Rosière de Charenton. (A rosière is a village maiden singled out and celebrated for her chastity, usually on the occasion of a fair or a festival; as for Charenton, it is a small Paris borough on the rivers Seine and Marne.) Foottit played an English journalist, and Chocolat was "a prince of Dahomey" mistaken for a servant; there was a lot of water frolics and, at the end, Chocolat had his revenge by destroying the podium on which stood the rosière and the officials, thus making everybody plunge into the water…

The season 1893-94 opened with Le Yacht de Monsieur Durand, which couldn’t even make it across the Nouveau Cirque’s water basin: It sank every night joyously and spectacularly! Émile Blavet, the chronicler of the Parisian daily Le Figaro, who signed his reviews "Un Monsieur du Balcon," ("A Balcony Gentleman") noted that such pantomimes "do not pretend to make us think, they are content with making us laugh. And here lies the secret of the continual success of Mr. Donval’s pantomimes…" Mr. Durand and his yacht sank at each performance, causing great hilarity in the audience, until Boule de Siam, a lavish "pantomimeA circus play, not necessarily mute, with a dramatic story-line (a regular feature in 18th and 19th century circus performances). à grand spectacle" succeeded it in January 1894.

Titled after Guy de Maupassant's short story Boule de Suif (1880), but with no other connection with it whatsoever, it was a spectacular exotic affair, with sensuous bayaderes, snake charmers, intrepid explorers and Lockhart’s elephants, who played musical instruments. Foottit was an English explorer who, at some point, was decapitated by a snake (an old clown illusion), to which his colleague remarked, "It’s alright, it has happened to me several times!" Chocolat was the hero of the farce, unable to marry the girl he loved because of the color of her skin (white…). Eventually, the explorers solved the problem by whitening Chocolat with an "American process"—as opposed to the contrary, colonial racism obliging! Indeed, Donval didn’t pretend to make us think…

In March 1894, le Nouveau Cirque once again presented a pantomimeA circus play, not necessarily mute, with a dramatic story-line (a regular feature in 18th and 19th century circus performances). built around a café-concert star—this time the very popular London-born singer Harry Fragson (1869-1913). It was L’agence Bidard ("The Bidard Agency"), which was pretext to a staged audition of talents, performed by either pretty girls or the clowns—with Chocolat, wearing a dress embroidered with faux pearls and diamonds, giving a hilarious impersonation of Caroline Otéro, known as "La Belle Oréro" (1868-1965), the notorious dancer, actress, and courtesan to the kings. Of course, Fragson was the last to "audition" and had his usual success. It was a dry pantomimeA circus play, not necessarily mute, with a dramatic story-line (a regular feature in 18th and 19th century circus performances)., but Fragson alone attracted a large audience.

Le Moulin du Gué ("The Ford by The Mill"), the "folie nautique" (nautical folly) that followed, was an extended version of the classic clown entrée(French) Clown piece with a dramatic structure, generally in the form of a short story or scene. "The Military Service." At the end of the piece, recalcitrant soldiers tried to escape and were chased by their sergeant and his men; eventually, as they were trying to cross a river through a slippery ford, all of them fell into the water… It was probably not the best of the Nouveau Cirque pantomimes, but it enjoyed a visit by the Prince of Wales (soon to be Edward VII), who certainly would have preferred to watch Chocolat’s impersonation of Otero: She was, it was rumored, one of his "acquaintances!" The season ended with a reprise(French) Short piece performed by clowns between acts during prop changes or equipment rigging. (See also: Carpet Clown) of the old stalwart, La Noce de Chocolat.

Change of Scenery

Meanwhile, the Parisian circus scene was beginning to change. Paris’s oldest circus, the Cirque des Champs-Élysées (open in 1843), also known as Cirque d’Été, had lost a good part of its horse-loving clientele to the Nouveau Cirque, and the building’s old age had become all too apparent. Open only during the summer (the Cirque d’Hiver was its winter counterpart), during which it was in competition with the mighty Hippodrome de l’Alma, it had become increasingly obsolete and would close its doors in 1899. In Montmartre, Louis Fernando’s financial situation had gone from bad to worse and, in 1897, he would leave his circus, the building of which already belonged to his creditors. (It was to be rescued by none other than Geronimo Medrano.)

But before that, the huge, state-of-the-art Hippodrome de l’Alma (it had, among other amenities, a glass roof that could slide open), home to popular equestrian extravaganzas and spectacular pantomimes, had lost its land lease and, despite continued success since its opening in 1877, it was forced to give its last performance on November 1st, 1892. Located avenue de l’Alma in an up-and-coming area, it was demolished to allow a lucrative real estate development. The entrepreneurial Donval saw in the Hippodrome’s demise an interesting opportunity.

He and he and a group of investors decided to erect a new hippodrome, to be named the Cirque-Hippodrome du Champ de Mars, in the former Palais des Beaux-Arts, a leftover of the 1889 Exposition Universelle that was not in use anymore. The new Hippodrome opened to great acclaim in July 1894. Like the previous Hippodrome, it was active only during the summer season, and would become the summer residence of the Nouveau Cirque’s company. Geronimo Medrano was appointed as its director.

Meanwhile, the Nouveau Cirque continued its successful series of pantomimes, and reopened at the end of September 1894 with reprises of Donval’s Papa Chrysanthème and, in November, Le Yacht de Monsieur Durand. Finally, at the end of November, came Pirouettes-Revue, the traditional end-of-the year revue, which was, noted the weekly La Jeune Garde, not so much a revue as a succession of tableaus in which, "amongst the clowns’ frolics, dainty lady dancers came and went, sometimes as bicyclists, sometimes as toreadors, sometimes as wrestlers complacently undressed in pink leotards…" Foottit was the revue’s compère (Master of Ceremonies); it was a joyous revue, full of action and pretty girls, but quite forgettable.

America, however, a "bouffonnerie exotique" (exotic buffoonery) that opened on January 12, 1895, was one of these water pantomimes that made Parisians rush to the Nouveau Cirque. Set in the American West (thus its "exoticism"), it culminated in the spectacular vision of a train, replete with its steam locomotive and baggage wagon, crossing a bridge that gave way under its weight, precipitating it, its passengers and their luggage into the water! A joyous collective bath followed, in which participated clumsy rescuers. This was the kind of pantomimeA circus play, not necessarily mute, with a dramatic story-line (a regular feature in 18th and 19th century circus performances). Cocteau must have remembered when he said that "No trickAny specific exercise in a circus act., no gag of the cinematograph will ever replace this wonder"—for, at the time, the cinematograph as a spectacle didn’t even exist: the first public performance of a movie by the Lumière brothers would occur that same year at the Grand Café in Paris, on the 28th of October!

La Reine de Bercy, which followed in April, reprised the theme of La Rosière de Charenton, but without the racist undertones Chocolat’s role had implied in the latter pantomimeA circus play, not necessarily mute, with a dramatic story-line (a regular feature in 18th and 19th century circus performances).. La Reine de Bercy (Bercy is a Paris neighborhood on the Seine river) was about the festivities surrounding the crowning of Bercy’s rosière. It ended with a competition in which young men had to climb a greasy pole erected in the middle of the pool; they reached it with a dinky, unstable embarkation and as they were climbing up, the pole began to sway while fireworks started accidentally; panic ensued and everybody fell into the water… The season ended with a reprise(French) Short piece performed by clowns between acts during prop changes or equipment rigging. (See also: Carpet Clown) of Pierrot Soldat, Foottit’s old warhorse, with a scenery designed by Caran d’Ache.

The caricaturist and satirist Caran d’Ache (1858-1909) was born Emmanuel Poiré in Moscow, in a French family established in Russia; he emigrated to France when he was nineteen, and adopted the professional pen-name of Caran d’Ache, from the Russian word Карандаш (karandash), which means pencil. A member of the Cirque Molier’s crowd, Caran d’Ache came up with his own water pantomimeA circus play, not necessarily mute, with a dramatic story-line (a regular feature in 18th and 19th century circus performances)., La Petite Plage ("The Little Beach"), written with the actor and sometimes playwright Arnold-Jules Fordyce. Starring Chocolat as a bandleader and Foottit as a banjo player, it opened the 1895-96 season. As its title implied, it was a perfect vehicle for water gambols and featured pretty naiads who were suddenly disturbed by a seal in their midst. Clumsy gendarmes came to the rescue, and after chases in all directions and an avalanche of gags, it all ended in a big splash.

Caran d’Ache and Fordyce reiterated in November with a "dry" pantomimeA circus play, not necessarily mute, with a dramatic story-line (a regular feature in 18th and 19th century circus performances)., Paris-Parade, which was an ode to the "Cirque romantique." It featured Foottit & Chocolat, and an interesting aerial ballet in which a swarm of pretty girls dressed as angels impersonated the clappers of hanging bells. Then, on January 31, 1895, the Nouveau Cirque presented another "dry" pantomimeA circus play, not necessarily mute, with a dramatic story-line (a regular feature in 18th and 19th century circus performances)., Coco. Coco was Chocolat, playing an exotic animal keeper at Paris’s Jardin d’acclimatation, which was then a mixture of zoological and ethnological park exhibiting the human, animal and botanic curiosities of the French colonies. (Today a children amusement park, the Jardin d’acclimatation is located in the Bois de Boulogne).

It is interesting to note that as Chocolat appeared in Coco and other pantomimes of the same type, the word raciste appeared in the French vocabulary (1894), followed by the concept of racism (1902)—for once again, the poor Chocolat (Coco) was the victim of mistaken identity with racist undertones: Trying to leave (or to escape) the Jardin d’acclimatation by night, he was mistaken for a monkey… Then, two wedding parties brought their share of confusion, into which Coco participated, and a chase ensued with its loads of visual gags. But it was also an opportunity to show exotic animals (an elephant, a camel, an ostrich...) and Coco ran until the end of March 1896. (The triumphant colonialism of the turn-of-the-twentieth century would soon bring traveling menageries into the European circus’s fold.)

Donval’s Final Years

In a move to make the Nouveau Cirque ever more profitable, Donval had instituted the "Cabaret du Chien Noir" (inspired by Rodolphe Salis’s famous "Cabaret du Chat Noir"), which performed every night at 9:30 pm in the Nouveau Cirque’s second-floor foyer. Like its model in Montmartre, it featured chansonniers (singers who wrote their own songs, words and music, often of a topical nature), and spectators sat at tables to sip drinks—the cabaret’s primary source of income. It was designed to attract spectators independently from the circus, but circus patrons could indeed join after the show.

The Nouveau Cirque continued nonetheless to present remarkable acts and successful pantomimes. L’île des Bossus ("The Hunchbacks’ Island"), which followed Coco at the end of March 1896, starred Foottit as Pierrot, and Chocolat as his sidekick, who landed on an island where hunchbacks were the norm and despised the "flat backs." Sentenced to death, the "flat back" Pierrot-Foottit was saved by the King’s daughter, who happened to be a "flat back" herself. For some reason, the all affair ended with a fight among sailors standing in their little boats, and everybody fell into the water…

The company then moved to the Hippodrome du Champs de Mars for the summer season, and the Nouveau Cirque reopened at the end of September 1896 with Paris-Pékin, a new “bouffonnerie nautique” in three acts, in which travelers embarked on a train that took them in a flashIn juggling, to flash is the act of juggling objects in a move that is sustained for only a very short time. to Pekin (today’s Beijing)! There, they were entertained by a group of pretty "Chinese" girls performing exotic dances to "oriental" music written by the ever-prolific Laurent Grillet. The last tableau, according to the musical journal Le Ménestrel of September 27, 1896, was "a very successful apotheose, with lotus leaves emerging from the water and allowing very plastic young creatures to blossom in languid poses." The reviewer, however, was mostly impressed by the "priceless Foottit maneuvering his pack of kids" in the show preceding the pantomimeA circus play, not necessarily mute, with a dramatic story-line (a regular feature in 18th and 19th century circus performances)., and the Risley actAct performed by Icarists, in which one acrobat, lying on his back, juggles another acrobat with his feet. (Named after Richard Risley Carlisle, who developed this type of act.) of the Kellino Family.

After a short-lived reprise(French) Short piece performed by clowns between acts during prop changes or equipment rigging. (See also: Carpet Clown) of La Rosière de Charenton, the year ended with a "pantomimeA circus play, not necessarily mute, with a dramatic story-line (a regular feature in 18th and 19th century circus performances). paysanne" (peasant pantomimeA circus play, not necessarily mute, with a dramatic story-line (a regular feature in 18th and 19th century circus performances).), Le feu au moulin ("Fire in The Mill"), which was a widely expanded version of the clown piece known as "The house on fire." The watermill was set at the center of the water basin, Chocolat was the miller and Foottit was the Chief of a company of hapless firemen. Eventually, everybody tried to extinguish the fire, including a group of frogs (i.e. pretty girls in green tights)! Needless to say, it was a good opportunity for a grand collective bath.

When 1897 began, Le feu au Moulin was still going strong. Nobody suspected it yet, but this was going to be Raoul Donval’s and Geronimo Medrano’s last year at the helm of the Nouveau Cirque. After Pierrot aux Enfers, which opened on February 12 with Foottit as Pierrot in a pantomimeA circus play, not necessarily mute, with a dramatic story-line (a regular feature in 18th and 19th century circus performances). inspired by the legend of Faust, Raoul Donval presented the last pantomimeA circus play, not necessarily mute, with a dramatic story-line (a regular feature in 18th and 19th century circus performances). he would author, Les 100 kilos, a "bouffonnerie nautique" that opened on April 16. It was inspired by an association that actually existed in Paris, Le Club des Cent Kilos (The 100-Kilo Club), the potential members of which were required to weigh at least 100 kilos (220 lbs.) to be accepted!

Foottit & Chocolat were the inept waiters of a waterside restaurant where the hefty members of the 100 Kilos clubA juggling pin. had their annual meeting—during which they honored their weightiest colleague. There was an "aerial tramway" to transport the customers to the restaurant over the water, in the form of a simple cable with a sliding trapeze from which they had to hang, providing a cheap load of plunges and gags. Cheaters in the weighing competition were also thrown into the water—and the most successful gag was the sight of the huge 100-kilo counterweight used on the scale floating gently in the pool after having been overthrown into the water by the weight of a particularly heavy customer… As usual, the music was written by Laurent Grillet.

That was Raoul Donval’s farewell opus: In poor health, he decided to leave the Nouveau Cirque at the end of the season. He also left the Hippodrome du Champs de Mars—but the Palais des Beaux-Arts, where it was housed, was slated anyway for demolition in 1898, to make room for the upcoming Exposition Universelle of 1900. Sadly, Raoul Donval died soon after, on March 14, 1898 in his apartment at 247 rue Saint-Honoré, just two doors away from the Nouveau Cirque; he was only forty-six. That evening, the Nouveau Cirque remained dark. Donval’s passing not only marked the end of an era for the Nouveau Cirque, but it also coincided with the end of an era for the circus in Paris.

Enter Hippolyte Houcke

Donval’s appointed successor was the brilliant circus director Hippolyte Houcke (1852-1925), who had successfully managed the now-defunct Hippodrome de l’Alma. The son of Jean Léonard Houcke (1816-1877), who had once been the régisseur(French) The stage (or ring) manager—and sometimes Ringmaster—in a French circus. (See also: Monsieur Loyal) of the Cirque des Champs-Élysées, he belonged to a great French circus dynasty that had settled in Sweden and had been instrumental in the development of the Scandinavian circus—and would also leave its mark on Paris’s circus history. Hyppolite Houcke, who was well-known to Parisian circus aficionados, was a welcome addition to the Nouveau Cirque.

By December, however, the Nouveau Cirque had also lost its regisseur(German, from the French: Régisseur) In Russia, the equivalent of a theatrical director in the circus., Geronimo Medrano: In late October, Louis Fernando, the Cirque Fernando’s director, unable to pay rent to his building’s owner, had staged a moonlight flit. On the 25th, it was announced that the entire property, land and walls, would be auctioned off. Apparently, the sale was completed in November, and the new owners put the circus for rent. Geronimo Medrano couldn’t see the circus that had made him famous disappear: He quickly gathered the necessary capital and, in December, became the building’s new lessee. The fabled Cirque Medrano was born; it was to become the Nouveau Cirque’s main competition.

On September 17, 1897, the Nouveau Cirque reopened its doors for the 1897-98 season. Hippolyte Houcke prudently reprised Les Cents Kilos, whose success was already well established. Then, in November, he offered his management’s first original pantomimeA circus play, not necessarily mute, with a dramatic story-line (a regular feature in 18th and 19th century circus performances)., Au Texas, which brought back the American "exoticism" of its precursor, America, with the sensational addition of diving horses, a popular, albeit questionable attraction(Russian) A circus act that can occupy up to the entire second half of a circus performance. in the United States, which was beginning to make its way in Europe (and the presentation of which the Nouveau Cirque, with its deep swimming pool, and now Berlin's Circus Busch, were the only circuses able to accommodate at the time).