Difference between revisions of "Alessandro Guerra"

From Circopedia

(→See Also) |

(→Suggested Reading) |

||

| Line 81: | Line 81: | ||

* Alessandro Cervelatti, ''Questa Sera Grande Spettacolo'' (Milano, Edizione Avanti!, 1961) | * Alessandro Cervelatti, ''Questa Sera Grande Spettacolo'' (Milano, Edizione Avanti!, 1961) | ||

| − | * Raffaele | + | * Raffaele De Ritis, ''Storia del Circo — degli acrobati egizi al Cirque du Soleil'' (Roma, Bulzoni Editore, 2008) — ISBN 978-88-7870-317-9 |

* Antonio Giarola & Alessandro Serena, ''Corpo Animali Meraviglie – Le arti circensi a Verona tra Sette e Novecento'' (Verona, Edizioni Equilibrando, 2013) | * Antonio Giarola & Alessandro Serena, ''Corpo Animali Meraviglie – Le arti circensi a Verona tra Sette e Novecento'' (Verona, Edizioni Equilibrando, 2013) | ||

* Irina Selezniova-Reder, ''Цирк в Санкт-Петербурге первой половины XIX века'' (St. Petersburg State Academy of Theater Art, 2009) — ISBN 978-5-88689-057-0 | * Irina Selezniova-Reder, ''Цирк в Санкт-Петербурге первой половины XIX века'' (St. Petersburg State Academy of Theater Art, 2009) — ISBN 978-5-88689-057-0 | ||

Revision as of 04:18, 9 July 2024

Equestrian, Circus Entrepreneur

By Dominique Jando

The Italian equestrian Alessandro Guerra is one of the most important figures of the 19th century equestrian circus. A remarkable horseman whose vigorous, aggressive style (as well as his fiery temper) won him the nickname of "Il Furioso," he was also a versatile performer, a gifted circus director, a pioneer who managed a very talented company and traveled with it far and wide all over Europe with enough success to catch attention and leave his mark wherever he went.

Luigi Guillaume and Christoph de Bach

He was born in 1782 in the historic town of Rimini, on the Adriatic coast, in what was then the Papal States, at the southern end of the Emilia-Romagna region. His parents were Mauro Guerra and Clementina, née Bordini. His family’s origins are not known, but beside his striking equestrian talents, Alessandro was a multi-talented artist: acrobat, juggler, musician, and actor in pantomimes—which leads us to believe that he came from a stock of traveling entertainers, although this is just an assumption; his brother, Rodolfo Guerra, a talented equestrian in his own right, would hold a significant part in his future company.Guerra had been a pupil of the celebrated Italian equestrian and circus pioneer Luigi Guillaume, in whose company (the Gran Circo Olympico) he performed, touring the rich Italian "circuits" of theaters, open-air arenas, and politeamas—these polyvalent theaters that served as circuses as well as theaters. Then he joined Christoph de Bach's company, at Vienna's Circus Gymnnasticus in 1815, where the local press first mentioned of Alessandro Guerra as being an exceptional trickAny specific exercise in a circus act.-rider: By 1817, he was a major star of de Bach’s company. On May 17, 1818, at age thirty-six, Alessandro married nineteen years old Adelheid Elisa de Bach (Adelaïde, 1798-1832), Christoph de Bach’s daughter from his first wife, Rosalia, née Masson (1755-1820).

Besides Vienna, de Bach’s company had a great reputation in the German and Italian states, which they visited regularly. The circus season in Vienna began traditionally on Easter Monday and lasted generally six months. The company traveled extensively the rest of the year: In 1826, for instance, they appeared in Naples, Rome, Florence, Genes, Turin, Milan, Venice, Innsbruck, Munich, Augsburg, Nuremberg, Frankfurt-am-Main, Darmstadt, Stuttgart, and Prague.

That same year, during the 1826 season at the Circus Gymnasticus, a Viennese newspaper wrote about Alessandro Guerra: "He stands quite freely on one foot on an unsaddled horse, not running at a canter as usual, but at full gallop, in various positions, playing the guitar with as much ease as if he were sitting leisurely in an armchair." The breakneck speed at which he presented his exercises, notably his remarkable juggling on horseback, was one of his characteristics—one which helped him earn his now-famous nickname, "Il Furioso" ("The furious").

From Circo Romano to Cirque Olympique

tDe Bach’s company was a brilliant one, with such talents as the remarkable Italian equestrian Gaetano Ciniselli (1815-1881), a pupil of Adolphe Franconi and François Baucher, who will write an important page of Russian circus history; Sophie Avrillon-Kennebel’s family, with the very young ballerina on horseback Virginie Kennebel (1819-1884), her daughter, who will become a star and marry the famous French equestrian and director Victor Franconi; the ropedancer Jean Ravel of the peripatetic French family of mimes and ropedancers, and the Italian clown and tumbler Ludovico Viool—in addition to de Bach's second wife, the beautiful Italian equestrienneA female equestrian, or horse trainer, horse presenter, or acrobat on horseback. Laura de Bach (née Dionisy, 1805-1851) and, of course, Alessandro Guerra himself.Yet, Alessandro Guerra was the most prominent star of this very talented group, and after so many years in de Bach's shadow, he was ready to go on his own. He left Christoph de Bach at the beginning of the 1826 tour and formed with Jean Ravel a new company; with them, they took the Avrillon-Kennebel clan, Ludovico Viool, and Gaetano Ciniselli. After their debut in Vienna, the company embarked on extended tours of the Italian and German states, following in de Bach's footsteps. It seems that Ravel and Guerra soon parted ways, and Guerra's company took the name of Gran Circo de Cavalli, followed by Circo Romano, before adopting the name Cirque Olympique, a name with a Parisian bouquet that was then so fashionable that Laura de Bach also used it!

As the company was performing in Milan in 1832, Guerra's wife, Adelaïde, suddenly passed away; she was only thirty-four and left three young children, Laura Adelaïde (b.1822 in Naples), Faustina Elisa Maria, known as Lisette (b. 1823 in Rome), and Celia Felicia Petronella (b. 1825 in Italy). Alessandro was fifty. At that age, his exploits as a trickAny specific exercise in a circus act.-rider standing on a galloping horse were something of the past, and he had converted to high-schoolA display of equestrian dressage by a rider mounting a horse and leading it into classic moves and steps. (From the French: Haute école) riding, a specialty for which, as usual, he showed a great ability. The talented French equestrian (and future director) Louis Soullier had joined Guerra's company and was soon to defect for de Bach's (and, in 1840, married his widow, Laura de Bach).

Christoph de Bach died on April 12, 1835. Guerra went into a bitter rivalry with Laura de Bach, who had taken over her late husband's Circus Gymnasticus and its company. Nonetheless, the two companies joined forces later that year and performed together in the manège of the Belvedere Palace in Vienna, in the form of a competition between them, with various equestrian exercises and presentations that included a chariot race! On July 19, Alessandro remarried in Vienna with twenty-two years old Elisabeth (Elisa) Schier, an true Viennese equestrienneA female equestrian, or horse trainer, horse presenter, or acrobat on horseback. from his company, who was to give him two more children, Alessandro (b. July 9, 1837, in Vienna) and Clotilde (1840-1908), who will later marry Andrea Ciniselli, Gaetano's son.Guerra then resumed his tours and, as usual, traveled extensively, visiting the Italian states as Circo Romano (Milan, Florence, Bologne, Turin…) and Prague, Berlin and the German states as Cirque Olympique. The company saw new members come and go, among whom the equestrians Bastien Gillet (who had married Adrienne Franconi, Henri Franconi's daughter, and didn't hesitate to present himself as Bastien Franconi), Jean Gärtner, and Pasquale Amato.

In 1843, Guerra performed in Vienna in his old home, the Circus Gymnasticus, which was by then mostly rented out to various companies while Laura de Bach and Louis Soullier were touring the world. Alessandro Guerra, Jr., age six, was on the bill, along with Rodolfo Guerra, the talented Virginie Kennebel (now Mrs. Franconi and billed as such), who was singled out by the press, the famous German high-schoolA display of equestrian dressage by a rider mounting a horse and leading it into classic moves and steps. (From the French: Haute école) rider Julius Hager (1830-1889), and Leopoldine Lezensky (or, more correctly, Lezenskaya), a ballerina on horseback who was also a trickAny specific exercise in a circus act.-rider.

Hager and Lezensky, along with Guerra's old stalwart Ludovico Viool, were to participate in his most significant adventure: He had his eye set on what was then a largely untapped territory, the vast Russian Empire. The first circus company that had visited Russia was that of the celebrated French equestrian Jacques Tourniaire. He had first performed there in 1824 and, with his company, he had opened a circus in St. Petersburg in 1826, and another one in Moscow the following year—but both were ephemeral. Viool was with Tourniaire in 1826-27, and we may surmise that he told Guerra about these very successful experiences; yet no European circus company of note had taken the risk of another adventurous trip to Russia ever since.

The Cirque Olympique in St. Petersburg

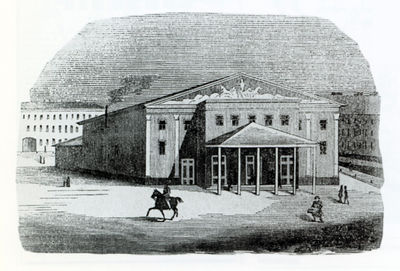

The circus had still to be developed in Russia, and Guerra was to become the catalyst of a significant movement to that effect—although, unfortunately, he will not gather the fruits of that experience. Nonetheless, in doing so, he will pave the way for many Italian circus families who will go to Russia and settle there, creating the very first Russian circus dynasties: the Truzzis, the Ferronis, the Bedinis, the Tantis and, not in the least, Gaetano Ciniselli, who will build in St. Petersburg in 1877 the magnificent circus on the banks of the Fontanka canal—which is today's Russia's oldest circus building, and still active.Guerra landed in St. Petersburg, the imperial capital, in the fall of 1845. He immediately set up to build a large amphitheater on the old Place des Manèges (the "merry-go-round square"), today's Театральная площадь (Theatre Square), in the shadow of Kamenny Theatre (the "stone theater", also known as the Bolshoi Theatre, or the Grand Theatre), which housed the Imperial Ballet and Opera companies. For a long time, this vast space had welcomed visiting fairs and their merry-go-rounds, but the presence of the theater had since redeemed its prestige, and Guerra found himself in ideal surroundings.

He built a large rectangular wooden structure that would have looked like a simple barn from outside, were it not for a pediment adorned with equestrian scenes on its front, and a little portico above the public entrance. It was simple, but comfortable enough inside and, as duly noted by the press, it was well heated—an important detail in a city where winters are long, snowy and quite frigid. The stables contained within the building had room for fifty horses. Alessandro Guerra and his troupe gave their first performance there on November 22, 1845.

The richness of the performers' costumes ("in the Parisian fashion"), the talent of the company's equestrians and, no less importantly, the beauty of its equestriennes guaranteed Guerra's enterprise an immediate success. His company, forty-strong, was particularly brilliant. It included Giuseppe Chiarini, who would create his own company ten years later and embark into amazing tours around the world; along with Joseph Verdier, Chiarini performed scenes on horseback in the manner of the famous British equestrian and director Andrew Ducrow (1793-1842).Rodolfo Guerra, Alessandro's brother, played opera arias on the flute while standing on the back of his galloping horse, and the high-schoolA display of equestrian dressage by a rider mounting a horse and leading it into classic moves and steps. (From the French: Haute école) rider Julius Hager rounded up this talented group of equestrians. Yet the male Russian aristocracy came principally to see Guerra's beautiful amazons, who were in large supply in his company: First, the gracious ballerinas on panneau(French) A flat, padded saddle used by ballerinas on horseback. (a large, flat wooden saddle on which the equestrienneA female equestrian, or horse trainer, horse presenter, or acrobat on horseback. performs as a ballerina): Louise Létard, who danced the zabadauda on her trotting horse, Josefina Guerra, Rodolfo's wife, who excelled at jumping over ribbons; and Leopoldine Lezenskaya.

Then, there was the exquisite high-schoolA display of equestrian dressage by a rider mounting a horse and leading it into classic moves and steps. (From the French: Haute école) rider Ellen Kremzow, a favorite of the European equestrian set, who later married the Austrian Count Mensdorff-Pouilly, and was the crown jewel of this bouquet of pretty equestriennes—which also included Maria Leb, Mathilde Baviera, Rosa Nellie, Marietta Orsanigo, and Angelika Hager. In a completely different genre, the clown acrobat Ludovico Viool, who was on his way to become a significant figure of the Russian circus, made a great impression.

However, and notwithstanding the true passions that his equestriennes triggered within the ranks of the aristocrats and officers who patronized his circus, the success of Guerra also came in good part from the fact that he offered his patrons something much more significant: They were exposed for the first time to the subtleties of high-schoolA display of equestrian dressage by a rider mounting a horse and leading it into classic moves and steps. (From the French: Haute école) dressage, until then little known in Russia, and which were not only gracefully demonstrated to them by the likes of Ellen Kremsow, but also taught by Guerra himself and Julius Hager. As a result, Guerra developed a patronage of wealthy regulars who met in the morning or afternoon around his manège, and often returned to the circus in the evening.

French Concurrence

Guerra changed his programs regularly, and his circus was now well established in the imperial capital, patronized regularly by the court and the Imperial family. Unfortunately, after nearly one year of unmitigated success, the rumor of the imminent arrival of another equestrian company spread over the gilded halls of St. Petersburg. To his consternation, Guerra discovered that it was the Cirque de Paris of Paul Cuzent, Jean Lejars (and, for the time being, Baptiste Loisset). The Cirque de Paris was Europe's premier and most successful company at the time.

Thus, in the fall of 1846, the Cuzent-Lejarses built another wooden circus in St. Petersburg, near the historic Alexandrinsky Theatre, a few yards from the elegant Perspective Nevsky. It opened its doors on October 8. The press noted that it was well heated and lighted (which, as we saw, was imperative) but that its narrowness rendered it uncomfortable, especially compared to Guerra's "vast" (in contrast) Cirque Olympique. Yet the comparison was not entirely to Guerra's advantage: the Cirque de Paris, it was said, gave a sensation of luxury, with its carpeted corridors, its warm colors, its fragrance burners which perfumed the house, and the flamboyant uniforms of its barrière(French) The line of uniformed artists and assistants who, in the old equestrian circus, stood at attention at the ring entrance to assist their fellow performers if needed. When seen today, the Barrière is usually made of the Ring Crew., the attending personnel at the ring entrance.Compared to his rival, Guerra's circus looked like "a gymnasium," whereas the Cirque de Paris was "a parlor." Guerra's supporters stressed that the Cirque de Paris did not have as many equestriennes as the Cirque Olympique, and that they were not as beautiful—with the notable exceptions, perhaps, of Pauline Cuzent, who had just celebrated her sweet sixteen, and whose "distinction was so perfect that the grandest ladies of the aristocracy asked her to teach them" (to teach them horse riding, that is), and the beautiful Madame Lejars, "La Taglioni du Cirque," Paul Cuzent's stunning sister Antoinette, who had married Jean Lejars.

The public soon realized that Mrs. Lejars and Cuzent were doing tricks that only men could achieve at Guerra's. And there was Paul Cuzent, at his peak at thirty-three, athletic and handsome with his dark looks, bellicose moustache, and his incomparable talent. If that was not enough for Guerra's regulars to swing toward the Cirque de Paris, they could also laugh there at the antics of their favorite clownGeneric term for all clowns and augustes. '''Specific:''' In Europe, the elegant, whiteface character who plays the role of the straight man to the Auguste in a clown team., Ludovico Viool, who, sensing the change of wind, quickly deserted Guerra and joined the competition! They could also cheer the juggler on horseback Jean Chancelet, the acrobatic feats of the brothers René and Jacques Dauvergne, and the young equestrian Jules Lejars—who was a mere four-year-old.

Guerra, however, didn't stay hands tied. One of his sponsors, the powerful Count Orlov, had presented him with 200,000 rubles, no less, to fight the invader, and Guerra used that money to beef-up his company. He called for his old companion Gaetano Ciniselli, the aerial gymnast Charles Price (a future British emulator of Jules Léotard, who worked, as Léotard would, with his father in tow), and, first and foremost, the Diva de la Cravache ("The Diva of the Whip"), the most illustrious Caroline Loyo (1820-1892), the greatest high-schoolA display of equestrian dressage by a rider mounting a horse and leading it into classic moves and steps. (From the French: Haute école) rider of the times, who trained her horses herself and the was first to ride them sidesaddle.

Yet, despite her talent, the volcanic Caroline failed to cast a shadow over her young rival, Pauline Cuzent, who was favorably compared to her (Pauline was "more refined," critics said), nor over the beautiful Madame Lejars, who ravaged the ranks of the local male aristocracy. The Cuzent-Lejarses also showed lavish pantomimes, in the Parisian fashion: Guerra had to follow suit, and although he was used to ending his performances with classic pantomimes, he had to renew quickly his repertoire, and his dwindling success was exhausting his funds. After three months of struggle, which only confirmed the Parisian company's artistic advantage, he threw the towel, packed his bags, and went back to his usual territory.

This "equestrian war" had fascinated St. Petersburg, including Czar Nikolai I, who visited the circuses several times with his family. (Prince Konstantin Nikolaevich took this opportunity to succumb to the beautiful Madame Lejars' considerable charms, and they experienced together, so it has been said, the joys and pains of adulterous escapades.) If Alessandro Guerra had to pay the price of the war, Paul Cuzent stayed in St. Petersburg and was given by the Czar the task of creating a Russia's Imperial Circus and the world's first circus school. But this is another story...

The Last Years

Guerra and his company went back to perform in the German States, visiting Berlin, Cologne and Munich. Alessandro befriended at this time the peripatetic German playwright, actor and author Karl von Holtei (17798-1880), whose successful novel Die Vagabunden ("The Vagabonds", 1851) was inspired in part by Alessandro Guerra's tales of his life. In 1849, Guerra performed in Stockholm, Sweden, at the newly built Mothanders Manege at the Djurgården, which stood of the spot of the present Royal Circus and had replaced Tourniaire's circus that had burned down the previous year.

In 1853, Guerra, who was now seventy-one, was in Turin, the capital of the Duchy of Savoy, in the Italian Piedmont. He continued his company's tours in the Italian states, Austria, the German states, and elsewhere in Europe but, as years passed, he didn't always meet not with the same success he had once enjoyed. In 1855, he was in Bordeaux, France, when, after a particularly bad business, he was forced to declare bankruptcy; to save his precious horses, he sold them to the French circus entrepreneur Louis Dejean, the owner of Paris's Cirque Napoléon (today's Cirque d'Hiver) and Cirque des Champs-Élysées.Alssandro Guerra passed away on July 5, 1862 in Bologna, in the region of his birth, Emilia-Romagna—where he may have retired. He was eighty years old. He is buried at Bologna's Cimitero Monumental della Certosa; a plaque on his grave reads: "Alessandro Guerra, supreme in the equestrian arts, whose mastery was always envied and never surpassed, lived among all the civilized people of the globe for 80 years. His widow, daughters and friends pay a tribute of tears and flowers to his body enclosed behind this marble." ("Alessandro Guerra, nei ludi equestri sommo, sempre invidiato ne mai vinto in sua maestria, fra tutte genti civili del globo visse anni LXXX. Alla salma di lui chiusa in questo marmo tributano lacrime e fiori la vedova, le figlie, gli amici.")

Sadly, his daughters didn't maintain the name Guerra in the spotlight, and his son, Alessandro Jr., vanished from the public eye. But there was a last person who did illustrate brilliantly the Guerra family name and its tradition: She was Rodolfo Guerra's daughter, the celebrated high-schoolA display of equestrian dressage by a rider mounting a horse and leading it into classic moves and steps. (From the French: Haute école) rider Elvira Guerra (1855-1937), who was born during the Cirque Olympique sojourn in St. Petersburg and became one of the greatest equestriennes of her generation; she was the first Italian woman to represent Italy at the Olympics in 1900. When she died in Bordeaux at age eighty-two, the Guerra dynasty disappeared with her.

See Also

- History: Russia's First National Circus

Suggested Reading

- Alessandro Cervelatti, Questa Sera Grande Spettacolo (Milano, Edizione Avanti!, 1961)

- Raffaele De Ritis, Storia del Circo — degli acrobati egizi al Cirque du Soleil (Roma, Bulzoni Editore, 2008) — ISBN 978-88-7870-317-9

- Antonio Giarola & Alessandro Serena, Corpo Animali Meraviglie – Le arti circensi a Verona tra Sette e Novecento (Verona, Edizioni Equilibrando, 2013)

- Irina Selezniova-Reder, Цирк в Санкт-Петербурге первой половины XIX века (St. Petersburg State Academy of Theater Art, 2009) — ISBN 978-5-88689-057-0