Difference between revisions of "Cirque d'Hiver"

From Circopedia

(→Image Gallery) |

(→Louis Dejean’s Circuses) |

||

| Line 13: | Line 13: | ||

[[Image:Cirque_des_Champs-Elysées%2C_c.1880.jpg|thumb|left|400px|Hittorff's Cirque des Champs-Elysées (c.1850)]]Dejean had sold his old Cirque Olympique in 1847; although it had been built only twenty years earlier (in 1827), it had already lost its appeal and was not practical anymore. Like many circus buildings of its generation, it had been designed with both a circus ring and a full theater stage, and consequently, it was easy for its new owners to transform it into a legitimate theater, the Théâtre du Cirque Olympique. With no permanent home in the winter, Dejean had taken to sending his troupe abroad, to London or Berlin. Although these forays into foreign lands had proved successful enough, having a new winter base in Paris still made more sense. | [[Image:Cirque_des_Champs-Elysées%2C_c.1880.jpg|thumb|left|400px|Hittorff's Cirque des Champs-Elysées (c.1850)]]Dejean had sold his old Cirque Olympique in 1847; although it had been built only twenty years earlier (in 1827), it had already lost its appeal and was not practical anymore. Like many circus buildings of its generation, it had been designed with both a circus ring and a full theater stage, and consequently, it was easy for its new owners to transform it into a legitimate theater, the Théâtre du Cirque Olympique. With no permanent home in the winter, Dejean had taken to sending his troupe abroad, to London or Berlin. Although these forays into foreign lands had proved successful enough, having a new winter base in Paris still made more sense. | ||

| − | Thus, Dejean asked Jacques-Ignace Hittorff (1792-1867), the City of Paris’s Chief Architect, to design the plans for a new circus. Hittorf had already built the Cirque des Champs-Elysées for Dejean, as well as its twin counterpart, the Panorama (today Théâtre du Rond-Point), which were part of the master plan for the renovation of the Chanps-Elysées gardens in the 1840s. Hittorff had also supervised the redesign of the Place de la Concorde (notably with the addition of his own monumental fountain, ''La Fontaine des Mers'') and he would later build Paris’s Gare du Nord, and many other "classic revival" pieces of work—a style of which he was one of the most influential proponents. | + | Thus, Dejean asked Jacques-Ignace Hittorff (1792-1867), the City of Paris’s Chief Architect, to design the plans for a new circus. Hittorf had already built the Cirque des Champs-Elysées for Dejean, as well as its twin counterpart, the Panorama (today Théâtre du Rond-Point), which were part of the master plan for the renovation of the Chanps-Elysées gardens in the 1840s. Hittorff had also supervised the redesign of the Place de la Concorde (notably with the addition of his own monumental fountain, ''La Fontaine des Mers'') and he would later build Paris’s Gare du Nord, the twelve ''hôtels particuliers'' (townhouses) that surround the Arc de Triomphe on tha Place de l'Étoile, and many other "classic revival" pieces of work—a style of which he was one of the most influential proponents. |

In the 1850s, on the area where the Place de la République stands today, the Boulevard du Temple arched and widened into a section that was popularly known as the ''Boulevard du Crime''—for the many crimes committed onstage every night in the melodramas that were the main fare of the Boulevard’s numerous theaters. With its alignment of theaters, cafés-chantants, and other popular attractions, the ''Boulevard du Crime'' was the heart of Paris’s entertainment district, a favorite destination for Parisians and visitors alike. | In the 1850s, on the area where the Place de la République stands today, the Boulevard du Temple arched and widened into a section that was popularly known as the ''Boulevard du Crime''—for the many crimes committed onstage every night in the melodramas that were the main fare of the Boulevard’s numerous theaters. With its alignment of theaters, cafés-chantants, and other popular attractions, the ''Boulevard du Crime'' was the heart of Paris’s entertainment district, a favorite destination for Parisians and visitors alike. | ||

Revision as of 19:28, 15 February 2020

Cirque Napoléon, Cirque National, Cirque d'Hiver

By Dominique Jando

Located in the heart of Paris, between the Place de la République and the Place de la Bastille, at the edge of the historical Marais, the Cirque d’Hiver is the world’s oldest extant circus building. It is also the world’s oldest circus still in activity: It first opened its doors in 1852. Its address, at 110 rue Amelot, may seem inconspicuous, but at that precise point, the rue Amelot opens onto the Boulevard du Temple through the small Place Pasdeloup: The Cirque d’Hiver is therefore quite noticeable, practically "on the Boulevards."

Louis Dejean’s Circuses

The Cirque d’Hiver (literally the winter circus) was built for circus entrepreneur Louis Dejean (1797-1879) as his circus company’s winter home. Dejean already managed the Cirque des Champs-Elysées, in the fashionable Jardins des Champs-Elysées, which he kept open from May through October. Up to 1846, his main establishment had been the Cirque Olympique, located some five hundred yards from his new circus, on the portion of the Boulevard du Temple that disappeared in 1862 to give room to the present Place de la République, during the renovation of Paris by the Baron Haussmann.

Dejean had sold his old Cirque Olympique in 1847; although it had been built only twenty years earlier (in 1827), it had already lost its appeal and was not practical anymore. Like many circus buildings of its generation, it had been designed with both a circus ring and a full theater stage, and consequently, it was easy for its new owners to transform it into a legitimate theater, the Théâtre du Cirque Olympique. With no permanent home in the winter, Dejean had taken to sending his troupe abroad, to London or Berlin. Although these forays into foreign lands had proved successful enough, having a new winter base in Paris still made more sense.Thus, Dejean asked Jacques-Ignace Hittorff (1792-1867), the City of Paris’s Chief Architect, to design the plans for a new circus. Hittorf had already built the Cirque des Champs-Elysées for Dejean, as well as its twin counterpart, the Panorama (today Théâtre du Rond-Point), which were part of the master plan for the renovation of the Chanps-Elysées gardens in the 1840s. Hittorff had also supervised the redesign of the Place de la Concorde (notably with the addition of his own monumental fountain, La Fontaine des Mers) and he would later build Paris’s Gare du Nord, the twelve hôtels particuliers (townhouses) that surround the Arc de Triomphe on tha Place de l'Étoile, and many other "classic revival" pieces of work—a style of which he was one of the most influential proponents.

In the 1850s, on the area where the Place de la République stands today, the Boulevard du Temple arched and widened into a section that was popularly known as the Boulevard du Crime—for the many crimes committed onstage every night in the melodramas that were the main fare of the Boulevard’s numerous theaters. With its alignment of theaters, cafés-chantants, and other popular attractions, the Boulevard du Crime was the heart of Paris’s entertainment district, a favorite destination for Parisians and visitors alike.

The piece of land Dejean was able to secure was situated at the eastern end of that section of the Boulevard du Temple, just before it became the Boulevard des Filles du Calvaire. Although the location looked like an afterthought in regard to the Boulevard du Crime itself, it was still a prime one. Yet the empty lot was far from ideal: it had very little depth, and was below street level. The place had to be leveled, and its lack of depth would prevent Hittorff from building the vast foyer that would have been expected for such a large amphitheater.

Hittorff’s New Circus

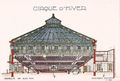

Nonetheless, the circus Hittorff began to build on April 15, 1852 was spectacular in many ways. It was a regular icosagon (a twenty-sided polygon), 42 meters (138’6”) in diameter, with a cupola reaching 27.5 meters (90’8”) at its peak. Its architectural peculiarity was that, unlike other circuses built before it, there were no columns inside the amphitheater to support its cupola: the surrounding walls, 55 centimeters (1’8”) thick and 16.25 meters (53’7”) high were reinforced at each angle by internal and external pillars that helped absorb the cupola’s weight.Unlike the Cirque Olympique, Dejean’s new building was not equipped with a theater stage. Not that Dejean had shunned it: Hippodramas were extremely popular in the mid-nineteenth century in circuses as well as in theaters—and circuses had a strong advantage over theaters since they could use both ring and stage for spectacular, action-filled, three-dimensional equestrian dramas. But the neighboring playhouses, which didn’t want to see yet another circus building transformed into a competing theater, had requested that the new circus be built exclusively for equestrian presentations—with a ring and no stage, like the Cirque des Champs Elysées—and Dejean had to yield to their wish in order to obtain his permit.

The house could accommodate 3,900 spectators distributed on three concentric seating sections, with standing room in a small promenade running around the periphery of the house, behind the last row of seats. The seating, which consisted originally of narrow benches covered with crimson velour, and with a stiff back support, was notoriously uncomfortable—a detail that chroniclers of the time never failed to mention. Today, the seats are conventional theater seats, and boxes have been added (in 1923) after the third row in the lower section—modifications that have lowered the capacity to 1,800 seats—but the space between each row has remained unchanged, and is still limited: for all its glory, the Cirque d’Hiver has never been a comfortable house!

The decoration of the house itself was indeed impressive. The most eye-catching element was (and fortunately, still is) the ceiling, inspired by the velaria used to protect the audience from the sun in Roman amphitheaters; its sheer size, as much as its rich ornamentation, makes it hard to miss—even today, in spite of the fact that its view as a whole is slightly obstructed by the lighting grid.

At the periphery of the house, a series of twenty paintings by Félix-Joseph Barrias and Nicolas-Louis Gosse, telling the history of horsemanship, adorned each panel of the polygonal wall. These are not visible today: They have been masked in 1955, and are now awaiting restoration. (A few of them have unfortunately disappeared, and others have been badly damaged by more than a century of neglect.) The house was lit by twenty ornate gas chandeliers distributed on its periphery, and by another giant chandelier above the ring.The stables, with room for 52 horses, were located in a long rectangular building at the back of the house, with a courtyard opening Rue de Crussol (a street perpendicular to the Rue Amelot). The building’s second floor accommodated the dressing rooms, various workshops, and living quarters at one end. Like the house, the stables were lavishly decorated; they included a superb fountain adorned with a bas-relief by the sculptor Astyanax-Scévola Bosio, which is still visible today.

Outside, the façade displayed two friezes running on the circumference of the building, sculpted by Bosio, Francisque-Joseph Duret (the author of the famous Saint-Michel fountain in Paris), Jean-Baptiste Guillaume, Eugène Lequesne, and Antoine Dantan—all artists of recognized talent and great reputation. The main frieze depicted the creation of the horse by Neptune, and its training by Minerva.

Two equestrian statues framed the entrance: a seductive Amazon by James Pradier on the left (which is said to have been modeled after the famous equestrienneA female equestrian, or horse trainer, horse presenter, or acrobat on horseback., Antoinette Lejars, and was the second version of a statue whose first version adorned the façade of the Cirque des Champs-Eysées), and a Greek warrior by Duret and Bosio, on the right. Frieze and statues are still in evidence today, but the Victory holding a lantern, which originally topped the building, has long disappeared.

The Cirque Napoléon

When the new circus opened its doors on December 11, 1852, nine months only after the beginning of its construction(French) A temporary circus building, originally made of wood and canvas, and later, of steel elements supporting a canvas top and wooden wall. Also known as a "semi-construction.", Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte, the nephew of the late Emperor Napoléon I, had just proclaimed himself Emperor of the French under the name of Napoléon III a few days earlier, on December 2.

This political event, however, hadn’t come as a surprise. After the fall of Napoléon I in 1815, France had reverted to a disappointing monarchy, during which a nostalgic cult of Napoléon and the Empire had steadily grown into a popular movement—fueled in no small part by the numerous pantomimes and hippodramas to the glory of the Emperor staged at the Cirque Olympique, and repeated (on a smaller scale) by other circuses.

After the abdication of King Louis-Philippe in 1848, the French Republic was proclaimed and Louis-Napoléon, back from years of exile in New York and London, had been elected its first President by a landslide. It then became obvious that the restoration of the Empire was lurking around the corner—and since its inception, the wily Dejean had called his new circus, Cirque Napoléon. And for his first official public appearance, the new Emperor himself inaugurated the circus that bore his name—or his uncle’s, for that matter.The Equestrian Director of the new Cirque Napoléon was Adolphe Franconi (1800-1855), heir to France’s first and foremost circus dynasty; its Régisseur (or Artistic Director) was Ferdinand Laloue; and its Equestrian Master, in charge of the all-important high schoolA display of equestrian dressage by a rider mounting a horse and leading it into classic moves and steps. (From the French: Haute école) (dressage) presentations, was the most famous equestrian and riding master of the time, François Baucher. The opening program offered to the Emperor included, among other artists, the celebrated clown Jean-Baptiste Auriol; the beautiful ballerina on horseback Coralie Ducos; and the god of horsemanship himself, the great Baucher.

On November 12, 1859, the Cirque Napoléon was the set of a historic event: The creation by a young French gymnast from Toulouse, Jules Léotard, of a new circus discipline, the flying trapezeAerial act in which an acrobat is propelled from a trapeze to a catcher, or to another trapeze. (See also: Short-distance Flying Trapeze). A marble plaque located just behind the curtain, on the right side of the ring entrance, still commemorates the event.

In 1861, the Cirque Napoléon began hosting the Concerts populaires de musique classique (Popular Concerts of Classical Music), which were presented each Sunday at 2:00 pm under the baton of Jules Pasdeloup (1819-1887). His orchestra, the Concerts Pasdeloup, still exists to this day, and the little square in front of the Cirque d’Hiver, which opens the rue Amelot onto the Boulevard du Temple, has been named Place Pasdeloup after the popular conductor. The Sunday concerts remained a tradition until 1884.

The Cirque d’Hiver

In 1870, after the humiliating defeat of Sedan in the war opposing France to Prussia, the deposition of Napoleon III on September 4, and the proclamation of the second French Republic, Dejean felt it wise to rename his circus, Cirque National. Dejean eventually retired two years later, in 1872, and his two circuses went under the management of Victor Franconi (1810-1897), Adolphe’s cousin, who had taught King Louis-Philippe’s children to ride, and had been the Ecuyer Privé (private riding master) of Napoléon III.

In 1873, Victor Franconi, whose republican feelings seem to have been hazy at best, finally gave the circus its present title, Cirque d’Hiver. (The Cirque des Champs-Elysées, which had been renamed Cirque de l’Impératrice during the Empire, and then Cirque National des Champs-Elysées in 1870, became the Cirque d’Eté—the summer circus.) Franconi, and his son Charles (1844-1910), who would succeed him, were among the last tenants of the great equestrian circus tradition. But Europe was entering the industrial age, and the audience’s tastes were beginning to change.Indeed, the circus, too, was changing with the times; not that great horsemanship had completely lost its appeal, but gymnastics and physical exercises were enjoying a growing interest. Léotard was in: He had become the circus’s first international acrobatic star—and, thanks to his tight costume (to which his name would remain associated) revealing his athletic figure, he became also one of the first sex symbols in show business. And sadly, the likes of Baucher and the Franconis, who had been among the brightest stars of the French equestrian circus, were already on their way out.

Additionally, the Cirque d’Hiver began to face serious competition. The American circus entrepreneur and former equestrian and clownGeneric term for all clowns and augustes. '''Specific:''' In Europe, the elegant, whiteface character who plays the role of the straight man to the Auguste in a clown team., James Washington Myers (1823-1892), had built a circus in the neighborhood, Place du Château d’Eau (the future Place de la République): the Grand Cirque Américain. Inaugurated in December 1875, it hosted Myers’ shows until 1879. Myers, who brought a new style and new acts to the Parisian audience, was extremely successful. When he was touring, the occasional tenants of his building were generally foreign companies (mostly Italian), which also gave a taste of novelty.

More importantly, in June 1875, the Belgian equestrian Ferdinand Beert (1835-1902), known as Fernando, had opened a new circus on the Boulevard de Rochechouart, at the foot of the Montmartre hill, the Cirque Fernando (which would become later, in 1897, the legendary Cirque Medrano). Then, in February 1886, the entrepreneur Joseph Oller opened the Nouveau Cirque, rue Saint-Honoré—a very elegant and comfortable circus, equipped with a state-of-the-art ring that could be lowered by a hydraulic system to reveal a water basin.While the Franconis maintained the old equestrian tradition in their two Parisian circuses, Fernando offered its popular audience a lighter fare, whose main attraction(Russian) A circus act that can occupy up to the entire second half of a circus performance. was the clown Geronimo Medrano, known as "Boum-Boum." Medrano was often the star of amusing topical revues written especially for him, while the Nouveau Cirque specialized in joyous water pantomimes—and would soon feature in them two clowns who were to become the toasts of Paris, Foottit & Chocolat. The Buffalo Bill’s Wild West also visited Paris in 1889, and so did the giant American circus Barnum & Bailey at the end of 1901. In the midst of all these novelties, the Cirque d’Hiver, staunch defender of the classical equestrian tradition, was increasingly becoming passé.

In the last decade of the century, Charles Franconi, following the lead of Fernando and the Nouveau Cirque, produced a series of pantomimes, old and new, in the ring of the Cirque d’Hiver. Some were successful, but still, Fernando and the Nouveau Cirque had become the circuses of choice for the Parisians—with a mostly popular and bohemian audience for Fernando, while the Nouveau Cirque catered to the elegant clientele that, before, had frequented the Cirque d’Eté. In 1899, just two years after the death of his father, Charles Franconi had to close his summer circus on the Champs-Elysées; he concentrated his efforts on maintaining the Cirque d’Hiver alive and profitable.

The Cirque d’Hiver In The Dark

But in spite of often interesting programs, the Cirque d’Hiver had lost its appeal. The dignified Place de la République, which had replaced the lively Boulevard du Crime, worked as a buffer between the theater district on the west side, and the short section of the Boulevard du Temple on the other side, where the Cirque d’Hiver stood alone, isolated from the bright life of the west-side "Boulevards." Finally, at the end of 1907, Franconi and his shareholders leased the Cirque d’Hiver to movie producer Serge Sandberg (1879-1981), who transformed it into a movie house for the Pathé Company. Charles Franconi didn’t survive this disgrace very long; he passed away three years later, in 1910.

A projection booth was built above the seats of the third section, facing the artists’ entrance—in front of which a movie screen had been erected—and the chandeliers disappeared. Obviously, a large part of the house could not have a good view of the screen. If only for its shape, not to mention its lack of comfort, the Cirque d’Hiver was not a very good movie house, especially as the movie audience was becoming more sophisticated.In 1917, Sandberg transformed for a time the Cirque d’Hiver into a theater. The great French actor Firmin Gémier (1869-1933), who was the proponent of a popular quality-theater with mass appeal, used the place for spectacular productions, such as a French version of Œdipe, Roi de Thèbes—following in the footsteps of Max Reinhardt’s own extravagant spectacle, Oedipus Rex (1910), which the German director had produced at Circus Schumann in Berlin, and which had become an international sensation. Gémier's theater experiment at the Cirque d’Hiver was the forerunner of the Théâtre National Populaire (TNP), which he created after WWI, in 1920.

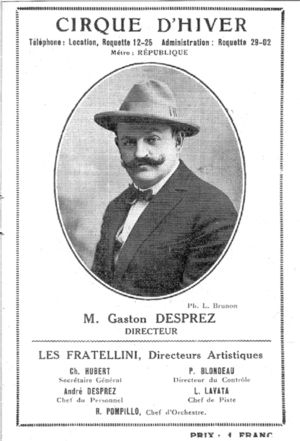

Then, the Cirque d’Hiver reverted to the movies, with the same mediocre success. Finally, in 1923, Serge Sandberg sold his lease to a theater entrepreneur named Gaston Desprez. Desprez came from a family of industrialists; he had developed equipment for the French Army during WWI, but his true passion was show business. He had already purchased movie houses in several provincial cities, managed a theater, and produced a circus show at the circus of Troyes, in the Champagne region. His two younger brothers, Marcel and André, shared his interests and had developed successful thrill acts for the circus.

Back To The Circus: Gaston Desprez

From the outset, Desprez announced his intention to give back the Cirque d’Hiver to circus arts, and his first move was to restore the building to its former glory. It had been carelessly modified during its years as a movie house and a theater, and was not suited anymore for circus performances: The ring, for one, as well as the stables, had disappeared. The architect put in charge of the project was Louis Gagey. The rehabilitation work lasted only three months, but was nonetheless extensive.

The internal structure was reinforced, especially the structure supporting the seating, which had been built in wood and was not in a very good shape; it was replaced by a support made of concrete. The seating itself was entirely refurbished with modern theater armchairs, and a row of boxes was installed behind the third row of seats in the lower section; it made the circus a little more comfortable, although the space between each row of seats was still limited. The house was repainted and redecorated, with notably a beautiful series of gilded winged horses, recovered from the short-lived (1866-1867) Cirque du Prince Impérial on the neighboring rue de Malte; they were placed above the vomitoires—the audience entrances to the house—and are still there today.

Backstage, the stables were reinstated in one aisle of their original building, and the other aisle was transformed into a vast foyer for the audience, decorated as a winter garden, with a fountain (which has since been removed) in the middle. In 1924, a painted frieze picturing all the acts that had been seen at the Cirque d’Hiver during the first Desprez season (1923-1924) was installed at the top of the foyer’s walls. It is still visible today. Among its subjects, a likeness of Charlie Chaplin is often seen as a tribute to the building’s past as a movie house; it is actually a picture of Charlie Rivel impersonating Chaplin’s Tramp character in Rivel’s trapeze act, Charlie and the Rivels.The new Cirque d’Hiver opened its doors on October 12, 1923. The former equestrian acrobat and clown Louis Lavata was the Régisseur de Piste (Equestrian Director), and Pierre Blondeau, Desprez’s future son-in-law and right-hand man, managed the front of the house. (Blondeau would later run a talent agency.)

When Desprez entered the arena, circus and variety were enjoying an unprecedented vogue in Paris—and the competition was fierce. Boulevard de Rochechouart, the Cirque Medrano had become more popular than ever, thanks in large part to the extraordinary success of a superlative trio of clowns, the Fratellinis. To be sure, the quickly aging Nouveau Cirque, rue St. Honoré, was reaching the end of its life (it would close in 1926), and the giant Cirque de Paris, opened in 1906 Avenue de la Motte-Piquet, was not faring much better (victim of its sheer size, it would close in 1930).

However, the Empire theater, which called itself "Music-Hall Cirque" and opened in 1924 with a mixture of variety and classical circus—on the model of the WinterGarten and the Scala in Berlin—became an immediate hit, and great circus acts regularly starred at the Folies-Bergère and the Casino de Paris, Paris’s legendary revue theaters, and in music-halls (variety theatres) such as the Olympia, the Alhambra, and Bobino.

Fortunately, Desprez saw big. He hired the best acts of the moment, including his brothers Marcel and André with their amazing double somersault in automobile—“piloted” by the stoic daredevil André, and especially built by Marcel, who was an engineer. In September 1924, Desprez scored a remarkable coup: Rodolphe Bonten, Cirque Medrano’s director, had foolishly denied the Fratellinis a salary increase for the new season; Desprez immediately lured them to the Cirque d’Hiver at their conditions, and named them Artistic Directors, a title more honorific than real, but which was clever advertising.

For the winter season of 1926, Pierre Blondeau signed and brought from the United States one of the most celebrated circus acts of all times, The Codonas, with the legendary triple-somersaulter Alfredo Codona. This was indeed another coup: the flying trapezeAerial act in which an acrobat is propelled from a trapeze to a catcher, or to another trapeze. (See also: Short-distance Flying Trapeze)’s brightest star in the circus where Léotard had invented the specialty! It definitely re-established Desprez’s Cirque d’Hiver as one of Europe’s premier variety houses, a circus to contend with. (The Codonas would return Rue Amelot in 1930.) Then, in 1927, the Cirque d’Hiver hosted for the first time the Gala de l’Union des Artistes, the original "circus of the stars" and Paris’s most prestigious gala benefitSpecial performance whose entire profit went to a performer; the number of benefits a performer was offered (usually one, but sometimes more for a star performer during a long engagement) was stipulated in his contract. Benefits disappeared in the early twentieth century., which had been held previously at the Nouveau Cirque. This tradition would continue until 1974. (It was resumed once, in 2010, in an unsuccessful attempt to revive its tradition.)

The Return Of Circus Pantomimes

In 1931, Desprez resumed the Cirque d’Hiver’s long tradition of circus pantomimes, taking his cue from Berlin’s Circus Busch, where the genre was flourishing with considerable success under the management of Paula Busch. The first of these spectacles was La chasse à courre ("The Dear Hunting"), a musical and equestrian piece, replete with horses, hounds, dears, and the Fratellinis, and featuring an interesting painted scrim surrounding the ring, which served as a set. A string of successful pantomimes would follow.

In the spring of 1932, Desprez launched an itinerant version of the "Cirque d’Hiver de Paris," which began touring the French provinces under a big topThe circus tent. America: The main tent of a traveling circus, where the show is performed, as opposed to the other tops. (French, Russian: Chapiteau) during the spring and summer season. Then, in November 1932, the Cirque d’Hiver hosted one of the famous water pantomimes of the other, itinerant Circus Busch (also known as Circus Busch-Nürnberg), Les nuits du Kalifat ("The Caliph’s Nights"), with an elaborate piece of equipment that transformed the ring into a water basin—albeit a rather shallow one. Les nuits du Kalifat was the forerunner of the spectacular water pantomimes that would make, in the years to come, the reputation of the Cirque d’Hiver.Lavish water pantomimes, which had been the trademark of Paris’s Nouveau Cirque, had been equally popular at Moscow’s Circus Nikitin, and at Blackpool’s Tower Circus each summer in England, and they were especially successful at Berlin’s Circus Busch. These circuses had all been equipped with a ring that could be lowered to reveal a water basin, and Desprez decided to install such a ring at the Cirque d’Hiver. Once more, he asked the architect Louis Gagey to design the plans for the new sinking ring and its water basin, while the technological aspect of the work was entrusted to the Castiglione engineering company.

The extensive work was completed in only one month. The basin, built of concrete, was 4.20 meters deep (about 14 feet), with a twenty-ton (metric) ring floor that could be lowered by a hydraulic elevator system; for this operation, the ring's heavy coco mat was removed, and the water passed through slots in the floor, as in the original system used before at the Nouveau Cirque. Openings in the basin's wall gave underwater access to the pool. The Cirque d’Hiver’s piste nautique (nautical ring) was inaugurated in November 1933 by the legendary meneuse de revue, Mistinguett (1875-1966), then France’s greatest variety star.

The water basin was not the only improvement Desprez brought to the Cirque d’Hiver for the 1933-1934 season: A small stage was added above the ring entrance—which could be connected to the ring with a removable staircase—and electric installations were modernized (with notably the addition of a crown of powerful lights under the cupola, and underwater lighting for the water basin). Finally, a roof was built over the Rue Amelot courtyard, which would allow, among other uses, proper housing for exotic animals when needed.

The first "water pantomimeA circus play, not necessarily mute, with a dramatic story-line (a regular feature in 18th and 19th century circus performances)." to use the new installations was Tarzan, a French adaptation of a Circus Busch’s original, with all the necessary equipment, set and costumes imported from Berlin. It lasted only one day: Unfortunately, Desprez had "forgotten" to secure the rights to the famous character created and closely protected by Edgar Rice Burrows... Elements of the show were hastily re-adapted by director Géo Sandry as a vehicle for the Fratellinis, Les Fratellini en Afrique ("The Fratellinis In Africa"), which didn’t fare very well.

Les Fratellini detectives, which followed, was not more successful. The summer tours of the Cirque d’Hiver big topThe circus tent. America: The main tent of a traveling circus, where the show is performed, as opposed to the other tops. (French, Russian: Chapiteau), even after Desprez re-named it Cirque Fratellini in 1933, had lost money. The new water basin and other renovations were still to be paid, and the recent productions had not recouped their costs. Maxime Morin, the President of the Société du Cirque d’Hiver (which had replaced Franconi’s Société des deux cirques) decided to terminate Desprez’s lease at the end of the season, and to offer the circus to the highest bidder.

Enter The Bouglione Family

The brothers Amar, whose traveling circus was one of France’s most prestigious, and who played Paris in the winter under a wood and canvas structure (known in French circus lingo as a construction(French) A temporary circus building, originally made of wood and canvas, and later, of steel elements supporting a canvas top and wooden wall. Also known as a "semi-construction."), began negotiating a lease. But they were quickly outdone by the Bouglione family, their main competitors who, like them, had debuted in the traveling menagerie business. The Bougliones accepted to assume the debt incurred by the recent renovation of the circus, which the Amars had been reluctant to include in the deal.

The Bougliones were a family of Sinti Gypsies. They had made their fortune with a successful hoax: After having purchased an old stock of unused posters for the 1905 French tour of the Buffalo-Bill’s Wild West, they had launched a colorful, if suspicious, Stade Buffalo-Bill in 1924. In spite of a very European circus program, they had managed to lure under its big topThe circus tent. America: The main tent of a traveling circus, where the show is performed, as opposed to the other tops. (French, Russian: Chapiteau) Belgian and then French provincial audiences, who were apparently content with a lively and rather exotic atmosphere (certainly owing more to the Bougliones’ vibrant Gypsy blood than to the American West) and a makeshift "Wild West" presentation at the end of the show.In 1928, the Stade Buffalo-Bill hit Paris; although the savvy Parisian circus and variety critics and a large part of the audience were not fooled, the Bougliones met with the same success in the capital as they had in the provinces. But the deception couldn’t last forever, and the following season, they abandoned Buffalo-Bill and began touring under a variety of names, before settling to their own in 1933: Cirque des 4 Frères Bouglione.

Their sudden arrival onto the Parisian circus scene, however, was the result of a quarrel with the brothers Amar over the acquisition a large group of elephants from the recently bankrupted Czechoslovakian Circus Kludsky, in which the Amars had finally outsmarted the Bougliones. The Bougliones took their revenge in derailing the Amars’ deal with the Société du Cirque d’Hiver. As the late Joseph Bouglione once told this writer, "We didn’t know really what to do with [the Cirque d’Hiver]: We had never had a sedentary life before; but it was a victory, and it was an opportunity."

Indeed, the Bouglione brothers (Alexandre, 1900-1954; Joseph, 1904-1987; Firmin, 1905-1980; Sampion, 1910-1967) seized the opportunity: More than eighty years later (as of 2013), the Bouglione family still owns and exploits the Cirque d’Hiver. Instead of just getting a lease on the circus, they made a deal with Maxime Morin, and became partners with him in the ownership of the old Cirque d’Hiver company. In time, the company would change names, and the Bougliones eventually remained its sole shareholders.

The Bougliones reopened the Cirque d’Hiver on November 17, 1934. The house had been repainted and refurbished afresh, and the opening had been preceded by a street parade, as the Bougliones used to do when they toured the provinces under canvas. Not to be outdone by the Amars, the parade displayed an important herd of elephants that included the Bougliones’ two pachyderms, three more borrowed to the Jardin d’Acclimatation zoological garden in Paris, and a group from Circus Althoff in Germany. Smart advertising indeed, since the most distinctive element the Bougliones were bringing to the Cirque d’Hiver was their important menagerie of exotic animals.

In January 1935, the Bougliones staged their first pantomimeA circus play, not necessarily mute, with a dramatic story-line (a regular feature in 18th and 19th century circus performances)., La reine de la Sierra ("The Queen Of The Sierra"), which began a long string of extravagant, often exotic spectaculars that included songs, music, wild animals, water frolics, and a cast of actors, singers, dancers, clowns, acrobats, and animal trainers supported by the extended Bouglione family. These spectacles were conceived by the prolific director Géo Sandry, and for them, ring, stage, and water basin were used at their fullest. For the 1935-1936 Holiday season, Géo Sandry produced what would remain the masterpiece of the genre—and a Bouglione staple until the 1960s—La perle du Bengale.

During WWII, and the German occupation of Paris (1940-1944), the Cirque d’Hiver reverted to simpler productions that mixed circus and variety, until the German occupants gave the management of the two Parisian circuses, the Cirque d’Hiver and Medrano, to Paula Busch and her son-in-law, the producer Emil Wacker, who had lost their circus in Berlin to city planning. They took possession of the Cirque d’Hiver on December 15, 1940. It was just a futile attempt at improving Franco-German relations through entertainment—and the Bougliones were soon allowed to repossess their circus, which reopened under their management on March 22, 1941. They continued to exploit it during the War with programs that mixed circus (with pantomimes that starred the clowns Alex & Zavatta), variety, and sport exhibitions.

The Post-War Era

The immediate post-war years translated into a boon for the circus industry throughout Europe. The Bougliones (who still toured with their Cirque Bouglione during the summer months, participated in other circus ventures, and rented out some of their animals to other circuses), took good advantage of the windfall. The Cirque d’Hiver was more prosperous than ever; the production of lavish pantomimes had resumed with considerable success, some of them serving as a comic vehicle for Achille Zavatta, who was well on his way to stardom.

In 1946, the Cirque d’Hiver was once again renovated, notably with a significant enlargement of the stage above the ring entrance—including the building of a large stage frame, in a style more reminiscent of the 1930s than of the Second Empire.

In 1955, the Cirque d’Hiver’s menagerie itself became an important draw as the Bougliones acquired a widely advertised adult gorilla named "Jacky." That same year, the circus became the setting for Carol Reed’s movie classic, Trapeze (1956), starring Burt Lancaster (who was a former circus acrobat), Tony Curtis, and Gina Lollobrigida—who was doubled in aerial sequences by Sandrine Bouglione. (It is for this occasion that the deteriorating paintings by Barrias and Gosse on the peripheral walls were covered by decorative elements and disappeared from public view.) Released the following year, Trapeze was an international success, and indeed an extraordinary advertisement for the Cirque d’Hiver. It is today an interesting documentary on the venerable Parisian circus at that time.The last original pantomimeA circus play, not necessarily mute, with a dramatic story-line (a regular feature in 18th and 19th century circus performances). produced at the Cirque d’Hiver (in 1958) was Davy Crockett et Jimmy Boy, which surfed on the wave of Disney’s international movie hit, Davy Crockett, King Of The Wild Frontier (1955). Afterwards, only a few scattered revivals of La perle du Bengale, in different shapes, lengths, and under various names, just served as a reminder of a long tradition that was now vanishing.

From 1954 to 1978, the Cirque d’Hiver hosted the long-running, monthly television show, La Piste aux Etoiles, which made the Parisian building familiar to anyone in France who had a TV set. The Cirque d'Hiver also continued to host annually the Gala de l’Union des Artistes until 1974, and the Gala de la Piste, with a few interruptions, between 1959 and 1980. In 1977, and from 1988 to 2006, the Festival Mondial du Cirque de Demain was also held for one week each year at the Cirque d’Hiver.

In 1981, French TV personality Yves Mourousi (1942-1998) produced the Mark Bramble, Michael Stewart and Cy Coleman's hit Broadway musical, Barnum, at the Cirque d’Hiver. For the occasion, the circus underwent again a series of renovations, notably the addition of new chandeliers above the second tier of seats on the periphery of the house, designed after the originals that had disappeared when the circus was transformed into a movie theater. The project included the restoration of the cupola decoration, the installation of a lighting grid, and the refurbishing of the circus’s corridors with marble floors. These improvements were paid for by the City of Paris—which compensated largely for the failure of the musical.

That event, however, opened new perspectives to the Bougliones. Since the 1960s, the Cirque d’Hiver had performed only three days a week and on holidays. Joseph Bouglione, the last of the original brothers was aging (he would pass away in 1987), and his sons, Sampion (b.1938), Emilien (b.1934), and Joseph (b.1942), had already ceased the tours of the once mighty Cirque Bouglione. (Joseph’s elder, Firmin (b. 1932), had left the family's enterprise and had established his own Cirque Bouglione in Belgium.) The circus scene was changing; the Cirque d’Hiver had trouble adapting to a new era, and was out of steam.

The Renaissance

In 1984, the Cirque d’Hiver became a house for hire, and began hosting a series of theatrical production, recitals, fashion shows, etc., with only a few incursions back into the circus world. Since 1986, the Festival Mondial du Cirque de Demain had occupied the ring for one week every year, and the burgeoning Cirque du Soleil performed there for one month in 1990. In 1997, Muriel Hermine, former Synchronized Swimming European champion, created and starred in Crescend’O, an aquatic show directed by Guy Caron, for which the old water basin, practically idle since the War, had been completely rebuilt.Then in 1998, the new generation met with the family patriarch, Sampion Bouglione II: Sampion’s son, Francesco, and Sampion’s nephews, Joseph Junior, Louis-Sampion, Thierry, and Nicolas, expressed their will to resume a circus season at the Cirque d’Hiver. Circus was back; most of the young Bougliones had performed in other circuses and varieté(German, from the French: ''variété'') A German variety show whose acts are mostly circus acts, performed in a cabaret atmosphere. Very popular in Germany before WWII, Varieté shows have experienced a renaissance since the 1980s. shows all around Europe, and they were well aware of the success of circuses that were defining new trends in the way of presenting circus performances. They wanted to be part of this circus renaissance.

After a few renovations, notably of the ring, which had slowly lost the characteristics of a true circus ring from one theatrical production to another, the Cirque d’Hiver reopened its doors as a full-fledged circus on October 1999, with a circus production titled Salto. Brilliantly cast, staged, lit, and costumed, accompanied by a superb orchestra, and with the participation of a seductive group of girl dancers (who would become known in following productions as the Salto Dancers), the show was an immediate and unmitigated success. Since Salto, a new production has graced the ring of the Cirque d'Hiver each year from October through March, meeting each time with increasing success. And in 2002, the production titled Le Cirque celebrated brilliantly the 150th anniversary of the Cirque d'Hiver.

In the summer of 2008, The Cirque d'Hiver's façade underwent an extensive restoration: vanished decorative elements were rebuilt; the friezes, which had been damaged over the years, were repaired; and so were the equestrian statues, external lights, stained glass windows, etc. The building's original colors were reinstated, and the painted frieze in the foyer was restored; the vibrancy of its original colors, muted by years of exposition to cigarette smoke, became visible again. Other restoration work, notably of the murals inside the house (which are badly damaged and have been hidden from view since the 1950s) is planned. After more than 150 years, the Cirque d’Hiver de Paris is younger than ever.

Suggested Reading

- Adrian, Histoire illustrée des cirques parisiens d’hier et d’aujourd’hui (Bourg-la-Reine, published by the author, 1957)

- Christian Dupavillon, Architectures du Cirque (Paris, Editions du Moniteur, 1982 — reprinted with additions in 2001) ISBN 2-281-19136-2

- Louis Sampion Bouglione and Marjorie Aiolfi, Le Cirque d’Hiver (Paris, Flammarion, 2002) ISBN 2-0801-0798-4

See Also

- History: The Bouglione Family

- Video: The Pantomime Robin des Bois at the Cirque d'Hiver (1943)

- Video: Cirque d'Hiver: A Visual History (2008)

- Video: Virtual Visit of the Cirque d'Hiver