Difference between revisions of "The Nikitin Brothers"

From Circopedia

(→The Nikitin Empire) |

(→The End Of An Era) |

||

| Line 58: | Line 58: | ||

Yet the circus scene was changing in Moscow. The old Circus Hinné had disappeared in 1892 to give way to the extravagant Morozov mansion (today the Foreign Ministry Mansion). Akim Nikitin’s only competition was the elegant Circus Salamonsky. But whereas Salamonsky had maintained the grand tradition of the aristocratic equestrian circus, Nikitin’s productions catered to a more popular audience—with an emphasis on thrill acts, exotic animals, and pantomimes. | Yet the circus scene was changing in Moscow. The old Circus Hinné had disappeared in 1892 to give way to the extravagant Morozov mansion (today the Foreign Ministry Mansion). Akim Nikitin’s only competition was the elegant Circus Salamonsky. But whereas Salamonsky had maintained the grand tradition of the aristocratic equestrian circus, Nikitin’s productions catered to a more popular audience—with an emphasis on thrill acts, exotic animals, and pantomimes. | ||

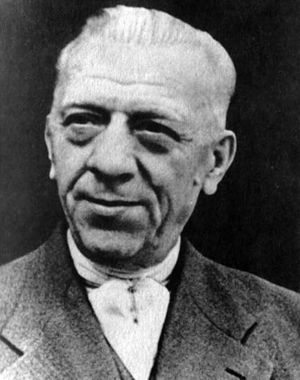

| − | [[Image:Nikolai_Nikitin_Portrait.jpg|thumb|300px| | + | [[Image:Nikolai_Nikitin_Portrait.jpg|thumb|300px|left|Nikolai Nikitin (c.1950)]]Albert Salamonsky would die two years later, in 1913, heralding the end of the Russian Circus’s first Golden Age. (A new Golden Age would come later, during the Soviet regime.) The following year, Russia was engulfed into the First World War. Without the old showman at its helm, Circus Salamonsky was falling apart—to such an extent that its employees decided to elect their own director, Yury Radunsky. Indeed, the Bolshevik revolution was looming on the horizon. |

Thus Akim Nikitin found himself without any serious competition. Circus Nikitin and Circus Salamonsky began to present programs that were increasingly similar in form and content. Then came 1917 and the Bolshevik revolution; on April 21 of that year, Akim Niktin passed away, at age seventy-four. (Dmitri passed away the following year, on January 13.) Akim’s son, Nikolai Akimevich (1887-1963), who had acquired a solid reputation as a juggler on horseback, took over the management of the circuses of the Nikitin empire, in Moscow and in the provinces. | Thus Akim Nikitin found himself without any serious competition. Circus Nikitin and Circus Salamonsky began to present programs that were increasingly similar in form and content. Then came 1917 and the Bolshevik revolution; on April 21 of that year, Akim Niktin passed away, at age seventy-four. (Dmitri passed away the following year, on January 13.) Akim’s son, Nikolai Akimevich (1887-1963), who had acquired a solid reputation as a juggler on horseback, took over the management of the circuses of the Nikitin empire, in Moscow and in the provinces. | ||

Revision as of 21:48, 8 January 2022

Circus Entrepreneurs

By Dominique Jando

In nineteenth-century Russia, circus was extremely popular among the aristocracy and the people alike, but the Russian circus was being developed mostly by foreigners whose names—Ciniselli, Truzzi, or Salamonsky—became synonymous with Russian circus. There was one notable exception, however: The Nikitin brothers, Dmitri (1835-1918), Akim (1843-1917), and Piotr (1846-1921), who became the first true Russian circus entrepreneurs of note, and would remain so until the Bolshevik revolution.

They were born to Aleksandr and Alina Ivanovna Nikitin, who were serfs attachd to one of the vast lands belonging to the Crown. Tsar Nicholas I began to ease the condition of the serfs bound to his Imperial estates in 1842, when he established the "quit-rent" system, which allowed them to leave the land to which they were attached in exchange for a rent paid to their landowner, the Tsar.

From The Balagans To The Circus

Aleksandr immediately took advantage of this new, if limited, freedom and became an itinerant organ grinder. His son Dmitri, who had learned to play the balalaika, followed him on the road. Akim and Piotr were born shortly thereafter, and almost as soon as they were able to walk and do a rollover, they joined forces with their father and elder brother, entertaining passersby from village squares to street corners.

In time, the brothers developed specific performing talents: Dmitri became a strongman; Akim, a front benderA contortionist who displays a front flexibility (as opposed to a back flexibility)., a juggler, and an augusteIn a classic European clown team, the comic, red-nosed character, as opposed to the elegant, whiteface Clown. (playing the Russian folk character of Ivan the Fool, always popular among the provincial audiences); and Piotr, a sword swallower, a tumbler, and a foot-juggler. They also formed an acrobatic trio together, and created a puppet show.The Nikitin brothers were versatile and hard working. When Tsar Alexander II definitely freed the serfs by his ukase of February 19, 1861, they began to find work on the country’s fairgrounds in the balagans(Russian) Fairground booths or theaters.—the fairgrounds' itinerant theaters. They would eventually create their own fairground show.

Still, the Nikitins had greater ambitions; they intended to escape the stigma of their former serfdom, and move upward; work on the fairgrounds, even in the best balagans(Russian) Fairground booths or theaters., had no glory. The circus was something else altogether: It was attended and enjoyed by the upper classes, and great circus artists received respect and, sometimes, even riches. Nicolas I had, in his time, created an Imperial Circus, and more recently, Carl Magnus Hinné and Gaetano Ciniselli had established themselves with great success in Moscow and St. Petersburg.

Although they were illiterate, the Nikitins were shrewd and had honed on the road a remarkable talent for scheming and survival. The foreign directors who ran the Russian circuses might have appeared well introduced in aristocratic circles, but the Nikitin brothers knew that, in actuality, they didn’t have much more formal education than themselves. Thus the former serfs and balagan(Russian) A fairground booth or theater. entertainers didn’t see any reason why they wouldn’t grab their own slice of the circus pie.

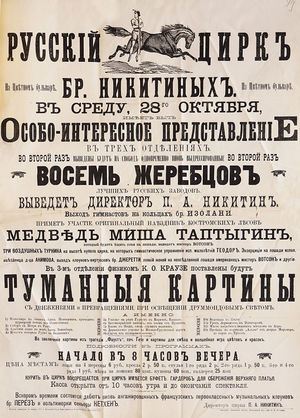

Dmitri, Akim, and Piotr Nikitin had saved money during their years of performing on the road; with it, they acquired the equipment of the Austrian circus of Emanuel Beránek (Beránek was Czech, but Czechoslovakia was then part of Austria), which had been touring the Volga region in the early 1870s. The purchase had come replete with tent, carriages, costumes, and horses, and on December 23, 1873, the Russian Circus of the Nikitin Brothers (Русский Цирк Братьев Никитиных) gave its first performance in the city of Penza. It was, at long last, the first genuinely Russian circus operating in the Russian Empire!

From Saratov to Moscow

The Nikitins’ Russian Circus toured the provinces with good success. Money was coming in, and three years later, in 1876, they were able to build their first permanent circus in Saratov, in southern Russia. Located in the center of the city, it was a wooden structure that was embellished over the years and stood until 1928. (It was demolished, and a stone circus was built in its place in 1931; in 1963, RosGosTsirk, the central Soviet circus agency, replaced it with a brand new, state-of-the-art building, erected in a different part of the city. This latter circus, which still bears the name of Nikitin Brothers’ Circus, remains active.)Owners of a permanent circus building and managing a touring company, the Nikitin brothers had finally entered the circus world’s big league. While Dmitri and Akim increasingly took care of the business, Piotr developed into a remarkable bareback rider (he is said to have mastered the somersault on horseback), a flying trapezeAerial act in which an acrobat is propelled from a trapeze to a catcher, or to another trapeze. (See also: Short-distance Flying Trapeze) and horizontal bars gymnast, a gifted mime, and even a quick-change artist.

Then the Nikitins struck gold: On the occasion of the coronation of Tsar Alexandre III in May 1883, they were invited to erect a temporary hippodrome at Khodinskoye Pole, an old parade ground in Moscow. Their hippodrome was a large open-air arena, inspired by the famous Hippodrome Franconi at the Barrière de l’Etoile in Paris, but whose actual configuration, with its two rings separated by a central stage, owed more to P.T. Barnum’s later version of it.

There, the Nikitins produced equestrian extravaganzas themed after old Russian legends, as well as chariot races and other traditional hippodrome fare. At the end of their run, which had been successful, they were awarded the Andreev Order’s Silver Medal by the City of Moscow. Then, they hit the road again. But now that they had experienced the great Russian metropolis—and its business potential—they longed to return.Meanwhile, the brothers were trying to expand their circus empire. In 1884, they built their second permanent circus in Minsk. It passed under city ownership the following year (it was destroyed during WWII, a replaced later by another building), but others would come.

Then, the wily brothers saw another golden opportunity in Moscow: The old Panorama (today, the Mir Theatre), adjacent to the circus Albert Salamonsky had built on Tsvetnoy Boulevard in 1880, was available. The circular building, which had once housed a panoramic painting depicting The Storming of Plevna, was an ideal fit for a circus, and its location on Moscow’s most popular promenade, in the midst of other places of amusement (including an already popular circus!) seemed perfect—at least to Dmitri, Akim, and Piotr Nikitin.

Thus the Nikitin Brothers’s Russian Circus opened in its new Moscow building in 1866. Their show certainly didn’t have the splendor of Salamonsky’s productions, nor his superb equestrian presentations, but the Nikitins knew how to attract a popular audience, and they met with increasing success.

Needless to say, Salamonsky was not amused—to put it mildly—and he finally bought out the Nikitins in 1887 for 30,000 rubles, a considerable sum for the time. He also had the Nikitins sign an agreement stating that they wouldn’t compete with Salamonsky in Moscow. To protect himself from another unwanted neighbor, Salamonsky used the old Panorama for horse training and equestrian exhibitions.

The Nikitin Empire

Salamonsky’s precautions proved useless: The following year (1888), the brothers returned to Moscow, where they rented the old Circus Hinné on Vozdzvizhenka Street (which belonged to Andrea Ciniselli). Furious, Salamonsky reminded the Nikitins of their agreement; but Akim and Piotr were quick to point out that it was Dmitri who had signed the agreement… Dmitri, as it happened, had just left his brothers and gone his own way. (He had created the Panoptikon, a traveling “museum” and menagerie.) Therefore, the Russian Circus of the Nikitin Brothers was not bound anymore by Dmitri’s agreements.Luckily for Salamonsky, the Nikitins didn’t do good business on Vozdzvizhenka Street and, before the end of the year, they left Moscow for Tiflis (today Tbilisi, in Georgia), where they built a wooden circus on Golovinsky Prospect (today Rustaveli Prospect). Tbilisi became their homebase, and from there, they created a touring circuit for which they used circuses of bricks or wood that they built over the years in several Russian cities.

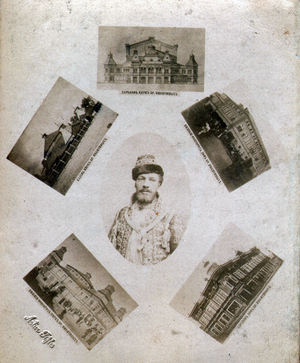

By the turn of the twentieth century, the Nikitins’ circus empire—and their well-oiled annual tour—included circus buildings in Tiflis (Tbilisi, which was the Nikitins’ home base), Baku and Astrakhan (where Circus Nikitin spent the winter season), Tsaritsyn (today Volgograd), Saratov, Samara, Kazan, Nizhniy-Novgorod, Ivanovo-Voznesensk, and Kharkov.

Piotr, the great artist of the family, retired from the circus in the 1890s. (He would pass away on August 20, 1921, having outlived his brothers.) Akim was left alone at the helm of the Nikitin Brothers’s Russian Circus. When his flagship circus in Tbilisi burned down, Akim finally decided to build a permanent circus in Moscow, where he found a vacant lot on Triumfalnaya Plaza and Bolshoya Sadovaya Street.

Designed by the architect Bogdan Mikhailovich Nilus, Circus Nikitin was a large stone building in the Art-Nouveau style with an imposing façade; it was equipped with a revolving ring that could sink to reveal a swimming pool—in the manner of Paris’s famous Nouveau Cirque—and which allowed the presentation of water pantomimes. Inaugurated in 1911, it has survived to this day as the Variety Theatre (formerly Theatre of Satire), but only its old circus cupola, still visible behind its new façade, betrays its circus origins.

The End Of An Era

Yet the circus scene was changing in Moscow. The old Circus Hinné had disappeared in 1892 to give way to the extravagant Morozov mansion (today the Foreign Ministry Mansion). Akim Nikitin’s only competition was the elegant Circus Salamonsky. But whereas Salamonsky had maintained the grand tradition of the aristocratic equestrian circus, Nikitin’s productions catered to a more popular audience—with an emphasis on thrill acts, exotic animals, and pantomimes.

Albert Salamonsky would die two years later, in 1913, heralding the end of the Russian Circus’s first Golden Age. (A new Golden Age would come later, during the Soviet regime.) The following year, Russia was engulfed into the First World War. Without the old showman at its helm, Circus Salamonsky was falling apart—to such an extent that its employees decided to elect their own director, Yury Radunsky. Indeed, the Bolshevik revolution was looming on the horizon.Thus Akim Nikitin found himself without any serious competition. Circus Nikitin and Circus Salamonsky began to present programs that were increasingly similar in form and content. Then came 1917 and the Bolshevik revolution; on April 21 of that year, Akim Niktin passed away, at age seventy-four. (Dmitri passed away the following year, on January 13.) Akim’s son, Nikolai Akimevich (1887-1963), who had acquired a solid reputation as a juggler on horseback, took over the management of the circuses of the Nikitin empire, in Moscow and in the provinces.

The Bolshevik revolution, however, had triggered the departure of most of the foreign circus performers who used to work in Russia, and often composed the majority of the acts in a program. It became increasingly difficult for the circuses to keep a good level of artistic quality, to the dismay of old circus aficionados (such as the writer Mikhail Bulgakov, who complained that, in Moscow, both circuses were offering an equal dose of vulgar mediocrity).

In 1919, the Russian circuses were nationalized and placed under the management of a central agency, the Committee for the Circus Arts. Nikolai Nikitin left Russia and went to work in Italy as a juggler on horseback. In 1921, the Committee for the Circus Arts, which had overseen the nascent Soviet circus with broad incompetence and a political agenda that had not much to do with the survival of circus arts, gave the management of the circuses of Moscow and St. Petersburg back to a professional, Williams Truzzi (scion of the great Italian family established in Russia), who had remained in the newly established USSR.

Circus Nikitin, which had been renamed Moscow’s Second State Circus (the "First" was the old circus Salamonsky on Tsvetsnoy Boulevard), eventually closed its doors in 1926: It had become too difficult to fill the programs of two circuses at the same time in Moscow (a problem that would lead to the creation, in 1929, of the State College for Circus and Variety Arts). The former Circus Nikitin was transformed into a variety theater.

Nikolai Nikitin returned to Russia in 1922, and continued a brilliant career as a juggler on horseback. Made Artist Emeritus of the Soviet Republic of Russia in 1947, he passed away on November 24, 1963. His son, Nikolai Nikolaelevich Nikitin (1912-1943), was also a talented juggler on horseback; he was killed on the front during World War II.

Suggested Reading

- Рудольф Евгеньевич Славский (Rudolf Evgenievich Slavskiy), Братья Никитины ("The Brothers Nikitin") (Mосква, Искусство, 1987)