Difference between revisions of "Elena Borodina"

From Circopedia

(→From Ballet Dreams To Circus Challenges) |

|||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | [[Image:Elena_Borodina_at_ZinZanni.jpg | + | [[Image:Elena_Borodina_at_ZinZanni.jpg|right|400px]] |

== Hand Balancer == | == Hand Balancer == | ||

Revision as of 05:37, 26 May 2023

Hand Balancer

By Dominique Jando

One of the greatest female hand-balancers of her generation, Elena Vyacheslavovna Borodina was born July 23, 1973, in Moscow, Russia, in a well-to-do family of scientists: Her father was a geologist, and her mother, a nuclear physicist. But as a child, Elena had ambitions of a very different order: She wanted to be a ballet dancer and, at a very young age, she began to take ballet lessons.

From Ballet Dreams To Circus Challenges

When she was nine, the required age to enter the Moscow State Academy of Choreography (better known as the Moscow Ballet School), Elena presented her candidature to the prestigious academy—the talent source of the Bolshoi Ballet. But she was then under medical treatment for a minor ailment, and that was enough for the Academy to refuse her application. Applicants had to be nine years old, not eight, nor ten: It was a one-shot-only opportunity, and young Elena was devastated.

Her best friend, and her neighbor, was Ekaterina (Katia) Denisova, with whom Elena had taken ballet classes. Ekaterina’s mother, Martha Avdeeva, was a scion of the old Avdeev circus family. Martha and her sister, Svetlana, had inherited the legendary "giant semaphore" act of the Koch Sisters—who were related to Katia’s grandmother (and namesake), Ekaterina.

Katia’s grandmother liked Elena and had started training her in basic circus disciplines. Since Elena wanted first and foremost to perform, Ekaterina suggested that she apply instead for the State College for Circus and Variety Arts (the famous Moscow Circus School), which was holding pre-auditions at the same period, before the summer vacation. This time, Elena, who was tall for her age (she grew fast in her early years, but would eventually reach a relatively small size as an adult), was judged too weak and too tall for an acrobat. That was for Elena another major disappointment. Her mother, however, was relieved: To her, circus folks were still rogues and vagabonds...

Then, friends told Elena about a small Amateur Circus—the Russian equivalent of a Youth Circus, albeit at a much higher level than in Western Europe or America—which was in their neighborhood (quite surprisingly, since it was the Red Square area), located in an old church hidden behind Moscow’s legendary luxury deli and grocery store, Yeliseyevsky. Little Elena went there by herself, and was immediately accepted: The good bases she had acquired in ballet classes and with Ekaterina had proven useful.

For four months, Elena spent three hours every day at the Amateur Circus, steadily building her strength. Being a Muscovite, she was allowed to re-present herself at the Moscow Circus School final selection in the fall, since the school didn’t have to take care of her lodgings and travel. She went through the same tests once again; the jury still had reservations, but found she had a good sense of balance, and thus a potential for balancing acts. Old-school teachers tended to like working on raw material, and one of them, Ivan Fedosov, strongly recommended that the panel accept her; they finally did. She was ten years old when she entered the circus world.

Early Training: Violetta Kiss And Ekaterina Mozorova

Elena spent her first four years at the School working on all circus disciplines, and continuing her academic studies, which were included in the program for the younger students. When time came for her to chose a specialty, she elected trapeze. But her mother thought it was too dangerous, and refused to sign a parental release. Then Olga Popova (Oleg Popov’s daughter) offered her to specialize instead in high wireA tight, heavy metallic cable placed high above the ground, on which wire walkers do crossings and various acrobatic exercises. Not to be confused with a tight wire. (which, in the USSR, was always performed with a safety line, or “longe(French, Russian) Safety line connected to a performer by a belt, going through a pulley, and held on the other end by an assistant, or a teacher. Also know as a ''mécanique'' (see this word).”)—but yet another teacher dissuaded her, arguing that the specialty was too restricted.

Finally, Elena decided to start working on hand balancing: She had always admired the style and precision of the legendary Violetta Kiss, the School’s foremost hand-balancing teacher, who had been given the privilege to handpick her students, and whose attention Elena wanted to attract. But she eventually ended in the class of Zinove Gurevich—the great Russian theoretician of circus acrobatics—who was also the first teacher of Oleg Izossimov.

Although at the end of the year, Elena had learned and mastered practically everything that could be done in hand balancing, she graduated as a circus generalist, and was invited to participate in group acts—something she didn’t want to do. Luckily, Violetta Kiss finally proposed to build an act for her.

Elena worked one year under Violetta Kiss, and developed a superlative technique which enabled her to master the most difficult tricks known to the specialty, including perfect alternate one-arm stands, jumping from one hand to the other. But Elena was not satisfied with her technical prowesses; she soon realized that if Violetta Kiss was indeed an extraordinary technical teacher, her style as an act choreographer emphasized too much the technical aspect of the act to the detriment of its artistic composition and originality.

Like many young circus students of her generation, Elena was impressed by the groundbreaking work of a new director, Valentin Gneushev, who was experimenting with the circus troupe of the Pravda plant, which he was heading. There, she thought, was an aesthetic she could relate to; she decided to leave Violetta Kiss, and to find a director who could help her build an act that would reflect her own personality. But she had only three months left before her final audition, and had to come up with a good act if she wanted to stay in the Soviet circus system.

Elena liked the work of Ekaterina Morozova, who had just created an eccentric acrobatic act in which two girls, Angela Strashnaya and Angelica Malkovka, performed acrobatic tricks while playing the saxophone. It was totally original—and also much too soon for the times. But she thought Morozova could be a good director for her, and Elena asked Ekaterina to help her with her hand balancing act.

Circus Debuts

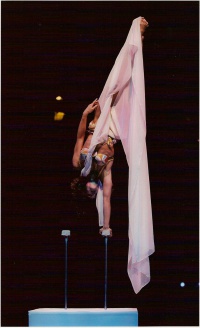

Morozova noticed that Elena could be very expressive with her leg movements, and suggested that she worked with her legs and feet to her accompanying music while in balancing position. She also suggested that Elena used a light fabric(See: Tissu) hanging from her toes, an element that would become her trademark. The result was an act in which there were practically no specific hand-balancing tricks: Just an upside-down dance.

When Elena showed her act to the panel of teachers and representatives of SoyuzGosTsirk, the Soviet central circus organization, they hated it: They contended that she didn’t perform any trickAny specific exercise in a circus act. beside standing upside down (notwithstanding the fact, however, that she could keep the position steadily for more than three minutes in a row) and that her act was too lascivious and sexually expressive. Mostly, they didn’t want to forgive her for leaving the tutelage of Violetta Kiss. They wanted her out.

But there was a dissenting voice, and a powerful one at that: Tatiana Assovskaya, the head of SoyuzGosTsirk, who had a knack for spotting potential talent among young performers, and who was always willing to help them. Assovskaya accepted the act, on the condition that Elena rework it with Morozova and add a few proper hand balancing tricks to her presentation. The year was 1991.

Elena Borodina’s first contracts with her new act were an engagement in the company of Teresa Durova’s new Moscow Clown Theater, and a tour of the Moscow Circus in Japan. But she soon realized that she had difficulty finding good work. Meanwhile, she saw that Valentin Gneushev’s acts were garnering awards at international circus festivals and, most importantly, were increasingly in demand on the international market.

Valentin Gneushev And Silencio

Ekaterina Morozova decided to send a DVD of Elena’s act to Valentin Gneushev, who proclaimed that it had to be entirely reworked. When Gneushev opened his own studio in 1993 at Circus Nikulin in Moscow, Elena joined up. For the next four years, she would be in and out of the studio, working with the temperamental director between scarce engagements of her old act in various minor shows in Russia and Germany.It was a long process, with many experiments and U-turns; but it started taking a clear direction when Gneushev asked Elena to research all what she could on the iconic American dancer, Isadora Duncan. Gneushev was not a hands-on director: He has a mostly suggestive approach, leading Elena in her own discovery of her act. After four years, she was still experimenting on an act that couldn’t evolve much further. She told Valentin Gneushev that she needed to perform it in front of an audience.

Gneushev took Elena to her word, and told her that she would be in Circus Nikulin’s next show, Етим Детям (For These Children), slated to debut in three weeks! Elena had no costume, no music, no props. The costume that was hastily designed for her was a catastrophe, and Michael Ekimian’s music for her act was delivered on opening day! Only her pedestal was in its final form: a cube (a shape that fitted the props related to theme of the show), with a fan inside that gently blew on the veil hanging from her toes.

Elena went on anyway, and her new act, titled Silencio, finally debuted in 1997 at Circus Nikulin, in Moscow. Elena's mother didn’t like her daughter’s act—but Valentin had always told her never to listen to anybody’s opinions, and although she was hurt, Elena dismissed the criticisms. In time, her costume was redesigned, and her music fine-tuned; Clemens Zipse, the producer of Palazzo, a leading German varieté(German, from the French: ''variété'') A German variety show whose acts are mostly circus acts, performed in a cabaret atmosphere. Very popular in Germany before WWII, Varieté shows have experienced a renaissance since the 1980s., came to see the show, and immediately offered Elena a contract. Elena Borodina was on her way to stardom.

In 1998, she participated in the festival Circus Prinsessan in Stockholm (an all-woman circus festival), and began working steadily in various German varietés. She eventually moved to Germany. Elena was then invited to participate in the Festival Mondial du Cirque de Demain in Paris in February 2001, where the was awarded a Silver Medal, and in 2001-2002, she was featured in Trapèze at the Cirque d’Hiver-Bouglione in Paris.

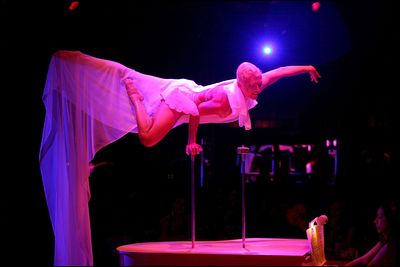

In 1999, Elena Borodina appeared for the first time in the United States at Teatro ZinZanni, the celebrated American varieté(German, from the French: ''variété'') A German variety show whose acts are mostly circus acts, performed in a cabaret atmosphere. Very popular in Germany before WWII, Varieté shows have experienced a renaissance since the 1980s. show, in Seattle. She soon became a regular of ZinZanni shows in San Francisco and Seattle—where she eventually settled, before moving to Las Vegas. At Teatro ZinZanni, Elena Borodina gave a beautiful new version of her act performed on a white grand piano serving as a pedestal—replete with a pianist at the ivories!

Elena eventually remained in the United States, and continued her career both in Europe and America. Between engagements, she began teaching hand balancing, and developed a successful hand-balancing method named Silencio, after her act, that mixes acrobatics and yoga techniques, and is aimed at yoga practitioners.

See Also

Video: Elena Borodina, hand balancing, at the Festival Mondial du Cirque de Demain in Paris (2001)