Difference between revisions of "Cirque Medrano (Paris)"

From Circopedia

| Line 5: | Line 5: | ||

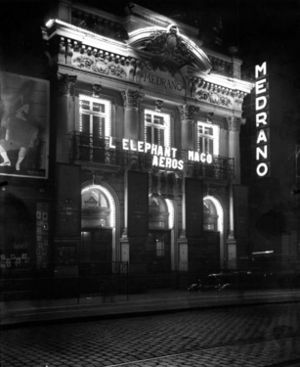

Sometimes referred to as "The Temple of Clowns," it has featured many of the world’s greatest clowns, from Geronimo Medrano to [[Buster Keaton]], and launched the extraordinary career of the [[Les Fratellini|Fratellinis]]. It had also sent into the limelight hitherto little known performers of immense talent, transforming them into genuine circus stars; appearing in its ring was a recognition for any circus artist. Its last performance under Jérôme Medrano’s reign in January 1963 was an event attended by the Tout-Paris of the arts, and its demolition in December 1973 caused a massive uproar that eventually led to a legislation protecting Paris’s historic theaters. | Sometimes referred to as "The Temple of Clowns," it has featured many of the world’s greatest clowns, from Geronimo Medrano to [[Buster Keaton]], and launched the extraordinary career of the [[Les Fratellini|Fratellinis]]. It had also sent into the limelight hitherto little known performers of immense talent, transforming them into genuine circus stars; appearing in its ring was a recognition for any circus artist. Its last performance under Jérôme Medrano’s reign in January 1963 was an event attended by the Tout-Paris of the arts, and its demolition in December 1973 caused a massive uproar that eventually led to a legislation protecting Paris’s historic theaters. | ||

| − | |||

| + | |||

| + | [[File:Medrano_Farandole.jpg|right|300px]] | ||

===Ferdinand Beert=== | ===Ferdinand Beert=== | ||

Revision as of 20:26, 30 July 2023

By Dominique Jando

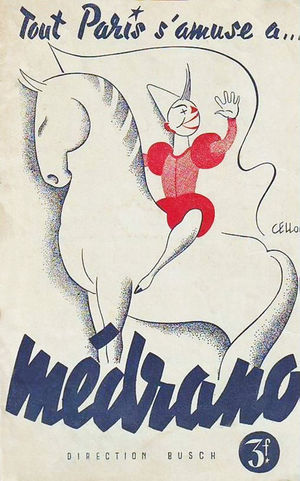

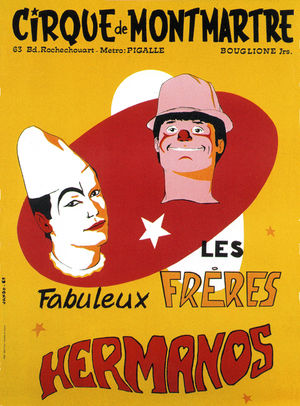

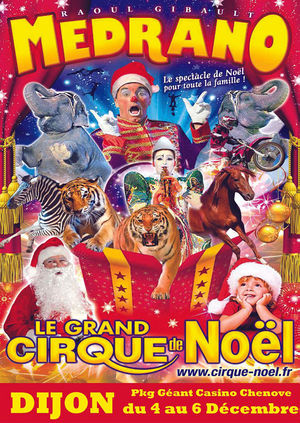

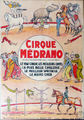

Paris’s legendary Cirque Medrano holds a singular place in the Parisian cultural fabric(See: Tissu) and in circus history. From its beginnings as Cirque Fernando, in 1873, until the end of Jérôme Medrano’s management in 1962, it was tightly woven into the artistic life of the French capital, not only as a popular place of entertainment, but also for its long association with artists, writers, journalists, and Paris’s intelligentsia in general. It has been celebrated in paintings, novels, movies, and even popular songs. Its history is also closely intertwined with the life of its three historic directors: Louis Fernando, Geronimo Medrano, and Jérôme Medrano.

Sometimes referred to as "The Temple of Clowns," it has featured many of the world’s greatest clowns, from Geronimo Medrano to Buster Keaton, and launched the extraordinary career of the Fratellinis. It had also sent into the limelight hitherto little known performers of immense talent, transforming them into genuine circus stars; appearing in its ring was a recognition for any circus artist. Its last performance under Jérôme Medrano’s reign in January 1963 was an event attended by the Tout-Paris of the arts, and its demolition in December 1973 caused a massive uproar that eventually led to a legislation protecting Paris’s historic theaters.

Contents

- 1 Ferdinand Beert

- 2 LE CIRQUE FERNANDO (1875-1897)

- 3 LE CIRQUE MEDRANO (1897-1962)

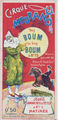

- 3.1 "Boum-Boum" Medrano, Circus Director

- 3.2 Change Of Guard

- 3.3 Berthe Medrano’s Circus

- 3.4 The Bonten Era

- 3.5 Enter Jérôme Medrano

- 3.6 Medrano’s Golden Age

- 3.7 Innovations And Expansion

- 3.8 Medrano Voyageur

- 3.9 Before The Storm

- 3.10 The War Years

- 3.11 The Post-War Era: The Floor Show

- 3.12 To America And Back

- 3.13 The Early Fifties

- 3.14 The Survival Years

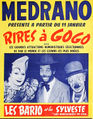

- 3.15 Swan Song

- 3.16 The End

- 4 Epilogue

- 5 Suggested Reading

- 6 See Also

- 7 Image Gallery

Ferdinand Beert

This most Parisian of circuses was actually built by a Belgian circus entrepreneur. Ferdinand Constantin Beert (1835-1902) was born July 31, 1835 in Courtrai, Belgium, to Auguste Jean Beert, a butcher, and Delphine Beert, née Steinbrouk. As legend has it, at age eleven Ferdinand "ran away and joined the circus"—in this case the Cirque Gauthiez, which was touring in Belgium. There, as the story goes, Ferdinand trained with an acrobat and worked as a groom, learning the basics of horsemanship on the job. Yet, how Ferdinand’s career actually evolved after his auspicious flight from home remains conjectural, but he did actually work for Gauthiez.

On April 17, 1857, Ferdinand Beert married in Bruges Maria Theresia De Seck, a Belgian equestrienneA female equestrian, or horse trainer, horse presenter, or acrobat on horseback. who, like him, was not born in the circus: Her father, Pieter, was a bargeman. Ferdinand was twenty-two; Maria Theresia already had a son, Ludovicus Carolus (Louis Charles), born in Bruges on July 26, 1851, probably out of wedlock, whom Ferdinand adopted. Louis-Charles (the future Louis Fernando, 1851-1917) was then six years old, just fifteen years younger than his new stepfather. The Beerts toured with the Cirque Gauthier in Belgium, Holland, Germany, and England. During this time, Louis was being trained as an equestrian—against his will, it must be said.

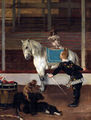

In 1861, Ferdinand Beert was hired by Louis Dejean (1786-1879), the famous French circus entrepreneur, for his Parisian resident company. Beert performed for the first time in the French capital at Dejean’s Cirque Napoléon (today’s Cirque d’Hiver), and then, for the summer season, at his Cirque de l’Impératrice on the Champs-Elysées. For his first appearance with Dejean, Ferdinand presented an acrobatic duet on horseback with his partner, Armand, and performed a barrel-vaulting act. Ferdinand Beert, who was a very versatile all-around performer, remained with Dejean for ten consecutive years, appearing in a wide variety of acts, on horseback and on the ground, as well as in clown entrées and in pantomimes.In time, Louis Beert would perform the same equestrian repertoire as his father’s, but after a bad fall in 1865 in which he suffered a broken leg and a broken arm, Louis was forced to abandon bareback riding. The great Equestrian Master François Baucher (1796-1873), who was Dejean’s equestrian director, decided to take Louis under his wing and teach him the intricacies of true horsemanship—from classic haute-école(French) A display of equestrian dressage by a rider mounting a horse and leading it into classic moves and steps. (See also: High School) to presentation of horses "at liberty"Liberty act", "Horses at liberty": Unmounted horses presented from the center of the ring by an equestrian directing his charges with his voice, body movements, and signals from a ''chambrière'' (French), or long whip.." Their sedentary years in Paris also gave Ferdinand and Maria-Tereza Beert the possibility to give Louis a solid academic education.

While working for Dejean, Ferdinand acquired a stage name, Fernando, and most importantly, a good knowledge of the Parisian audience. He had had also ample opportunity to observe at close range how Dejean managed his circuses. In the summer of 1871, Fernando appeared for the last time at the Cirque des Champs-Élysées—the Cirque de l’Impératrice’s new name after the fall of Napoléon III’s Second Empire in 1870. He would not return to the newly named Cirque National (formerly Cirque Napoléon) for the winter season: Contemplating the dawn of a new Republican era, Fernando Beert had decided to start his own circus!

LE CIRQUE FERNANDO (1875-1897)

Beert’s original Cirque Fernando, a traveling circus, was launched at Vierzon, a small town in France’s Center region, in the spring of 1872. The company included ten horses and five artists: Fernando and his stepson, Louis (now twenty-one), the equestrian Philippe Bertoletti, the trapeze artist and equestrian Baptiste Gillardoni, and the English clown George Howard. It was a small company, but the number of horses and the presence of four equestrians reveal that horsemanship was the performance’s main fare—not surprisingly, since the age of equestrian circus was still in full bloom.

Fernando’s roster of performers grew in number as his circus toured the French provinces with various degrees of success. As for Maria Theresia, now known as Marie-Thérèse, she had retired from performing and took care of the administration (i.e. box office and basic accounting); she was also quite busy bringing up the couple’s three children, Adolphe, Marthe, and Eugénie—of whom only Adolphe and Marthe would perform in the family’s circus—and she had perhaps lost the slender physical shape expected of a ballerina on horseback. She was now the respectable Mrs. Fernando.

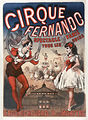

La Fête de Montmartre

In August of 1873, Fernando set up his circus tent at the Fête de Montmartre, a popular summer fair that was traditionally held on the hill of Montmartre, on the northern edge of Paris. The previous month, however, the French government had given the green light to the construction(French) A temporary circus building, originally made of wood and canvas, and later, of steel elements supporting a canvas top and wooden wall. Also known as a "semi-construction." of the Sacré-Cœur basilica on the open space where the fair traditionally took place, at the top of the hill. Consequently, the fair was moved down to the median walkway of the Boulevard de Rochechouart, on the southern edge of Montmartre. It was large enough to accommodate the fair’s booths and carousels, and even a traveling menagerie, but not a circus tent. Luckily, Fernando found an empty lot at the corner of the Boulevard de Rochechouart and the Rue Lallier, and was able to lease it for the duration.

Montmartre and its immediate vicinity formed a animated and colorful working-class neighborhood, already renowned for its many places of amusement: La Boule Noire, one of its better known dancing halls, was located just across the boulevard from Fernando’s lot; there were also the Bal Tabarin and La Reine Blanche, to mention just two of the most famous "bals" (dancing halls) that attracted revelers to the Boulevard de Rochechouart. The Moulin de la Galette, a "guinguette" (a tavern with dancing), was another popular rendezvous located on the hill itself; and soon, the Bal du Moulin Rouge would be added to the list (on the Boulevard de Clichy, the western continuation of the Boulevard de Rochechouart).Montmartre’s large bohemian population included many painters—among whom Auguste Renoir, Edgar Degas, Georges Seurat, and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec. They quickly became regulars of the Cirque Fernando, where Mrs. Fernando gave them free access to rehearsals to sketch the performers at work and, sometimes, to see the show. In turn, they brought in their wake a host of young trendsetting writers, journalists and other Parisian literati to the circus; these well-connected visitors would generate a considerable publicity for the Fernandos.

When it was originally set up in Montmartre, Fernando’s circus was a small canvas tent supported by a single pole, which offered rather spartan seating accommodations; with its worn wooden wagons surrounding the tent, and most of its artists living onsite, the whole affair looked like a gypsy encampment. Yet, Fernando’s show was commendable and had charm, and it was generally well received by the critics who made the trip to the Boulevard de Rochechouart.

More importantly, Fernando discovered that there was a large indigenous population ready to return to a local circus when its programs were renewed—to which could be added the many visitors who came to have a good time in this lively neighborhood. Thus, when the fair came to an end, Fernando extended his lease and replaced his tent by a semi-construction(French) A temporary circus building, originally made of wood and canvas, and later, of steel elements supporting a canvas top and wooden wall. Also known as a "semi-construction." with a canvas top over a wooden structure, and a boarded wall to keep it warm during the coming winter months.

The French novelist Jules Claretie (1840-1913) gave a good description of the Cirque Fernando at that time in his novel Le Train 17 (1877), in which his not-so-imaginary circus was named Cirque Francis Elton: "It was not a luxurious circus with seats covered with velours; it was nearly a traveling circus, and its rotunda, covered with canvas, grown, somehow, in the middle of Paris, suddenly, like some vegetation after the rain, had quite surprised the population of the Boulevard de Clichy..." Even though Claretie's story is indeed fictional, its setting and its main character, Francis Elton, are based on the Cirque Fernando of that period and its director, Ferdinand Beert.

By then, Fernando’s company of performers had expanded; in the spring of 1874, it included—beside the Fernandos, Bertoletti and Gillardoni—Ferdinand and Victor Bouthors; the equestriennes Clotilde Bertoletti, Mlle Marthe (Fernando) and Mlle Juliette; and most significantly, the clown Geronimo Medrano (1849-1912) and his partner, Pasquale. Unbeknownst to him, Medrano was on his way to stardom in a building that would one day bear his name—for Mrs. Fernando, who saw the money flowing in at the box office, had decided it was time to build a permanent circus in Montmartre.

The Circus That Fernando Built

At the beginning of 1874, the Fernandos had met with a Mr. Loiseau, owner of the ground where they were installed, and since Loiseau had no immediate prospect for his piece of land, they secured a thirty-year lease on a parcel located a few yards west of their construction(French) A temporary circus building, originally made of wood and canvas, and later, of steel elements supporting a canvas top and wooden wall. Also known as a "semi-construction.", at the corner of the Rue des Martyrs. Unlike the Rue Lallier, the Rue des Martyrs intersected the Boulevard de Rochechouart at a right angle, which made the design of a building easier. Furthermore, they could keep their existing circus structure active on its old spot during the construction(French) A temporary circus building, originally made of wood and canvas, and later, of steel elements supporting a canvas top and wooden wall. Also known as a "semi-construction." work.

Some circus historians have mentioned that no building permit has ever surfaced, thus inferring that the construction(French) A temporary circus building, originally made of wood and canvas, and later, of steel elements supporting a canvas top and wooden wall. Also known as a "semi-construction." of the Cirque Fernando had been somewhat illegal. However, this is a misconception: There were no building permits per se at the time, and the documents presented to the Prefecture de Police constituted in themselves the "permis de bâtir"—unless the Préfecture de Police opposed the construction(French) A temporary circus building, originally made of wood and canvas, and later, of steel elements supporting a canvas top and wooden wall. Also known as a "semi-construction." of a building on the planned location for a reason or another, but not related to any technical or architectural aspect of the construction(French) A temporary circus building, originally made of wood and canvas, and later, of steel elements supporting a canvas top and wooden wall. Also known as a "semi-construction.". It was just a routine procedure. Since nothing prevented the construction(French) A temporary circus building, originally made of wood and canvas, and later, of steel elements supporting a canvas top and wooden wall. Also known as a "semi-construction." of a circus on Fernando's chosen location, the work began on August 15, 1874.

To finance part of the operation, the Fernandos made an unusual deal with their building contractor, a Mr. Oudin. Oudin agreed to be paid in installments, and as a guarantee, the Fernandos transferred to him all their circus equipment, and even their lease. In turn, Oudin used Fernando’s properties and lease as collateral to obtain a credit of 100,000 francs from the Banque Bouley et Cie. In time, this financial arrangement would generate serious problems, and it would have unintended consequences that eventually resulted in Jérôme Medrano losing his circus to the Bouglione family nearly a century later.

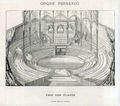

By the end of November, the circus's main infrastructure was completed; the new Cirque Fernando opened its doors seven months later, on June 25, 1875. Its address was at 63 Boulevard de Rochechouart, and it had cost over 500,000 Francs—approximately €5,775,000 today. In spite of a limited space (the usable surface was about 40 x 40 meters) and a relatively small budget, Gridaine had done a very fine job. The style was "classic-Haussmann," with a pleasant façade—albeit missing the equestrian statue that was meant to top it and was never made—ornamented with Corinthian columns framing three arched doors that led to a small reception hall, where the box office was located. Above the doors were the three French windows of the foyer standing above the reception hall, ornamented with elegantly designed wrought-iron balustrades.

The house itself was a sixteen-sided polygon with an inside diameter of 34.10 meters (35 meters outside). The ring had the traditional diameter of 13 meters. The roof, whose metallic frame remained fully visible, was divided in two concentric circles; the inner circle was an elevated cupola, 22.5 meters in diameter, supported by sixteen cast-iron columns. Its height, up to the base of the lantern, was about 20 meters. The peripheral wall of the central cupola had windows, and so had the lantern, so that sunlight could be used during rehearsals and matinees—but there were also sixteen large gas chandeliers hanging between the columns at the circumference of the cupola to lit evening performances.

Unlike the Cirque des Champs-Elysées and the Cirque d’Hiver, the various categories of seats were connected together, which generated a convivial environment. The steep gradient between the rows not only offered the audience an excellent visibility (notwithstanding the columns in front of the Second Places), but also very good acoustics—a definite plus for the clowns. The house was nicely decorated with garlands of flowers painted on the periphery of the cupola, and gold accents adorning architectural details. The columns were painted in faux marble, and the walls and ceiling in a shade of peach-pink. The house irradiated a feeling of warmth and elegance—and intimacy, which was not its lesser charm.

If the house was, of course, circular, the entire building was contained within a square. On the forefront, flanking the façade on each side, were two spaces designed to accommodate a coffee house and offices; starting in 1885, they were leased to the photographic studio Chamberlin, whose name would remain associated with the circus building until the late 1950s. In the back, behind the house, was a small two-story structure; on the street side, next to the stage door (at 72ter Rue des Martyrs), stood the concierge’s lodge and an all-purpose space that could house horses and animals. Fernando’s large apartment was located above, on the second floor.

On the opposite side, stables (with room for 16 horses) occupied the ground floor, and the second floor accommodated a suite of rather cramped dressing rooms for the artists. (Two additional dressing rooms were located below ground level, under the seats, on each side of the ring entrance—one of them traditionally used by the clowns). This side of the building had no door opening outside, since the small Rue Viollet-le-Duc, which would later flank the east side of the circus, didn’t exist yet (it was opened in 1880).

The backstage area, between the two aisles, was relatively narrow; it served nonetheless as a secondary foyer with a small buvette (refreshment stand), which, when the main foyer at the front of the house was later suppressed under Jérôme Medrano’s tenure, was replaced by a bona-fide bar where artists and spectators mingled during intermission—a beloved feature that added to the charm and uniquely convivial atmosphere of this circus.

The Circus That Medrano Also Built

The Cirque Fernando had already begun to develop its Parisian reputation during its canvas days, but now that it was performing in a permanent building, with the added comfort this implied, it quickly became a true destination. Mrs. Fernando continued her policy of giving the neighboring artists free access to rehearsals, and they continued to bring along their friends: Journalists and writers liked the new circus’s warm atmosphere, and Fernando Beert was able to deliver the quality they expected of its shows. They made it known.

Born in Madrid in 1849 to Candido Medrano and his wife Magdalena, née Perez, et, Geronimo trained in gymnastics as an adolescent and, at age twenty, built a flying trapezeAerial act in which an acrobat is propelled from a trapeze to a catcher, or to another trapeze. (See also: Short-distance Flying Trapeze) act with a partner, Leopold Salonne. Created in 1859 at Paris’s Cirque d’Hiver by Jules Léotard (1838-1870), the flying trapezeAerial act in which an acrobat is propelled from a trapeze to a catcher, or to another trapeze. (See also: Short-distance Flying Trapeze) had quickly become an act à la mode—albeit not an easy one to tackle—due to Léotard’s astonishing success. It was originally performed from trapeze to trapeze, but Medrano and Salonne were among the very first flying trapezeAerial act in which an acrobat is propelled from a trapeze to a catcher, or to another trapeze. (See also: Short-distance Flying Trapeze) artists to include passes from a trapeze to a suspended catcherIn an acrobatic or a flying act, the person whose role is to catch acrobats that have been propelled in the air.. Yet what truly set Medrano and Salonne apart is that theirs was a comedy act.

They had already performed all over Europe when they landed in Paris in June 1872, at the Cirque des Champs-Elysées, where they achieved a notable success. Although Fernando had already left Dejean’s company, he may have met Geronimo Medrano then and there. In any event, in 1873, Medrano and Salonne parted company, and Fernando Beert, who had now a circus of his own, offered Medrano to work for him as a clownGeneric term for all clowns and augustes. '''Specific:''' In Europe, the elegant, whiteface character who plays the role of the straight man to the Auguste in a clown team.; Geronimo was blessed with a warm and sunny personality and was immediately successful. He was also good at training small animals, and his favorite partner in the ring was a pig—a foil of choice to many a clown (as Billy Hayden, Tony Grice and, later, Anatoly Durov bear witness).

Quite often, clowns use in the ring a catchphrase that eventually becomes their trademark; Medrano used to give the bandleader the signal to play his exit music by shouting to him a resounding "boum boum!" ("boom boom!") . Geronimo’s recurring exclamation stuck, and very soon his audiences nicknamed him Boum-Boum. Although he was not specifically featured in Fernando’s advertising, a large part of the popular audience went to the Cirque Fernando to see Boum-Boum. He didn’t need to be announced: The audience knew he would be there. He was, so to speak, part of the furniture—and he contributed to a large extent to the Fernando's success.

Enter Louis Fernando

During its first summer recess in August 1875, the Cirque Fernando housed a series of concerts of "modern music." When it reopened in September, Fernando Beert’s stepson, Louis Fernando, was in charge of the programs—becoming in effect the circus’s Artistic Director. Why Fernando delegated this crucial responsibility to Louis? The Beerts were heavily in debt, and to add an extra income, Fernando had decided to resume the tours of his traveling circus, while he progressively left Louis in charge of the building.

Moreover, if Fernando knew how to run a traveling circus, the running of a Parisian circus was another matter altogether: It required to be constantly aware of the performers’ market, endlessly deal with artists or agents, be attuned to the trends of the moment, and most importantly, be very creative. Louis Fernando, who was a snob of sorts eager to be part of Parisian society, had a much better education than his stepfather and kept au courant with the fads of Paris life, and he had indeed a more genial personality. All in all, Louis was better suited than his stepfather to run a Parisian place of entertainment. In fact, Fernando Beert had rarely been in the limelight as a director: His wife and his stepson had always been the circus’s front persons.Louis proved to be a good artistic director; he knew how to compose attractive programs, was open to novelties, and understood well that he had to boost his best property, "Boum-Boum" Medrano. However, on the administrative side, the Beerts’ lack of financial acumen was their Achilles’ heel. In 1876, to satisfy the demands of their creditors, they tried to create a corporation, but the constitution of their capital, as it was, was judged illegal, and the corporation was dissolved. At this point, their financial and legal situation had become so complicated that it had created a vacuum in which Louis Fernando had ample room to move as he saw fit. The flip side was that the Beerts had nothing left to their name: All their properties, including their building and their land lease, were held as a security by their bank.

On January 25, 1876, Louis Fernando married into well-to-do Parisian bourgeoisie: The father of Jeanne Gabrielle Houssaye (1857-1894), his young wife, was a well-known tea merchant who had created the first Parisian tearoom on the Champs-Elysées during the Exposition Universelle (World Fair) of 1867. Louis and Jeanne Fernando took up residence at the Rue du Dôme, near the Place de l’Étoile in Paris, in a fashionable neighborhood. Together, Jeanne and Louis Fernando already had a son, Gabriel Eugène Henry Beert, born September 24, 1875, who had a lackluster career as an acrobat, married in 1900 the daughter of a railways employee, and died in 1902, at age twenty-seven. Over the years, Louis’s lifestyle, fueled by his social ambitions, will hurt his and his circus’s already shaky financial situation.

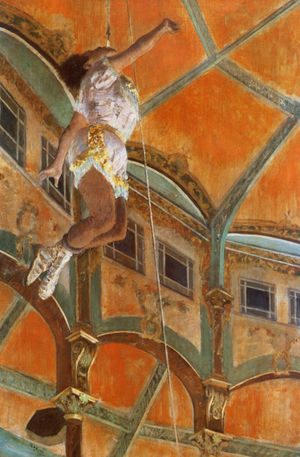

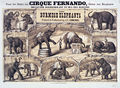

Nonetheless, Louis Fernando was a capable Artistic Director. He was aware that his circus was not equipped to compete efficiently in the equestrian department with the Cirque d’Hiver and the Cirque des Champs-Elysées, or to stage the spectacular pantomimes the Cirque d’Hiver, and soon, the huge Hippodrome de l’Alma (open in 1877) produced. The Cirque Fernando was, however, better tailored than its competition for intimate comedy, and it had a popular leading clown to boot. In January 1876, Louis produced Le Barbier Frétillant ("The Wriggling Barber"), a comic pantomimeA circus play, not necessarily mute, with a dramatic story-line (a regular feature in 18th and 19th century circus performances). with Boum-Boum in the title role. It was the first of a long series of similar pieces that featured Geronimo Medrano and made him a true circus star.Novelty acts, not star equestrians, were what set the Cirque Fernando apart—from an all-female equestrian show, to the riding seal of Raziscoff, or the lions of Captain Cardona. In December 1878, the sensation of the show was the Mulatto aerialistAny acrobat working above the ring on an aerial equipment such as trapeze, Roman Rings, Spanish web, etc. Miss Lala (Olga Albertina Brown, 1858-?), "la Sirène des Tropiques" ("The Tropics’ Mermaid"), who had a considerable Parisian success and was immortalized by Edgar Degas. (This show also featured the Fratellinis, in the person of Gustave Fratellini—the father of the legendary François, Paul and Albert—and his partner Gustave Romoli.) Miss Lala and the Kaira Troupe (in which she belonged) went on tour with the tenting Cirque Fernando during the summer and remained under contract with Fernando until the end of 1879.

When the Cirque Fernando went on its annual provincial tour under canvas in the summer of 1879, Medrano went to work at the Hippodrome de l’Alma, while the Fernando building was rented out and transformed into a café concert—a variety show featuring mostly singers, and where drinks were served. The circus would often be similarly rented out in the summer for extra-curricular activities, and during the season, on dark days, for public meetings or political reunions: The most publicized of them were meetings held by Georges Clémenceau, then the Député (M.P., or Representative) of Montmartre. (A major French columnist and politician, Clémenceau would become France’s Prime Minister in 1917, during WWI, and helped build victory over Germany.)

Geronimo Medrano was still Fernando’s top attraction(Russian) A circus act that can occupy up to the entire second half of a circus performance., and the central character of its joyous pantomimes. At the opening of the 1882 season, he was additionally promoted to the important function of Régisseur Général—a mixture of company manager and performance director specific to the circus: He was in charge of the performers, the crew, the rehearsals, and the performances. In his spare time, he also trained young equestriennes, such as the Cardinale Sisters, who performed at the circus as bareback riders in 1885.

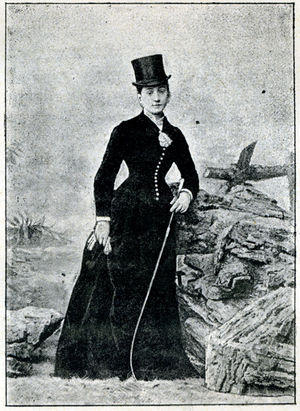

As for Jeanne Fernando, Louis’s wife, she had made her debut in 1881 as an haute-école(French) A display of equestrian dressage by a rider mounting a horse and leading it into classic moves and steps. (See also: High School) rider at the fashionable Cirque d’Amateurs that Ernest Molier presented annually in his Parisian townhouse on the rue de Bénouville, the courtyard of which had been converted into a small private circus. She had been trained in horsemanship by her husband, according to Baucher's method, and had become a remarkable equestrienneA female equestrian, or horse trainer, horse presenter, or acrobat on horseback.. "Madame Louis Fernando" was subsequently an intermittent equestrian feature of her husband’s circus: She was not in good health, which often took her away from the ring for long periods of time.

Competition

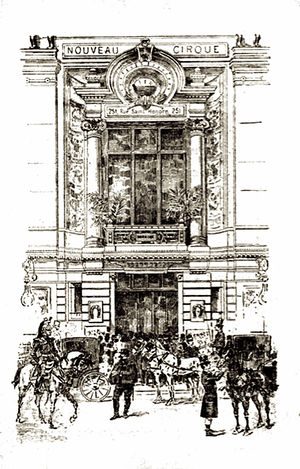

On February 12, 1886, Joseph Oller’s brand-new Nouveau Cirque opened its doors on Rue Saint-Honoré, in the prosperous center of Paris, at a stone-throw of the Place Vendôme. It was a revolutionary circus: Its ring could sink to reveal a water basin—the very first circus equipped with such a device. It had also a palatial and comfortable house (with individual theater seating) which had been designed by Fernando’s architect, Gustave Gridaine. However, the façade and the elaborate reception hall were the work of Charles Garnier (1825-1898), the celebrated architect of Paris’s extravagant Opéra, which gave the place an additional cachet.Beside its plush elegance and its chic surroundings, which would quickly make it the High Society’s circus of choice, the Nouveau Cirque had put together a brilliant company of artists, among which was a group of very talented clowns: George Foottit, Alexandre Pierantoni, and Tony Grice with his young apprentice, the Black augusteIn a classic European clown team, the comic, red-nosed character, as opposed to the elegant, whiteface Clown. Chocolat. The Nouveau Cirque also made good use of its water basin with comic pantomimes that inevitably ended with a big splash in the pool! Novelties and comedy had been so far what had distinguished the Cirque Fernando from Franconi’s more horse-oriented Cirque d’Hiver; now, Fernando had serious competition in its own particular domain from a better-located, and somehow more attractive circus.

Louis Fernando’s business remained good nonetheless, as he stuck to the recipes that had made his success. Although George Foottit, already a star clownGeneric term for all clowns and augustes. '''Specific:''' In Europe, the elegant, whiteface character who plays the role of the straight man to the Auguste in a clown team., loomed bigger than Medrano in the public eye, Boum-Boum was still attracting a faithful audience to the Boulevard de Rochechouart. Then, at the end of the summer of 1887, the touring Cirque Fernando ceased its activity (Fernando Beert probably retired soon after that). In 1888, the circus on the Boulevard de Rochechouart remained open during the summer three days a week; the rest of the time, Louis Fernando gave riding and vaulting lessons in the ring. Times were changing—and not for the better…

In January 1889, the Cirque Fernando offered En Selle pour la Revue, a humorous revue of the previous year’s events—the original meaning of a revue, a fashionable theatrical form then—written for "Boum-Boum" Medrano at his request by two well-known librettists, Surtac and Alévy (Gabriel Astruc, 1864-1938, and Armand Lévy, 1859-1935). Boum-Boum was the revue’s traditional compère (a mixture of Master of Ceremonies and stand-up comedian), and Louis Fernando, playing himself, was his straight man. It was a huge success that remained on the bill for three months, in spite of the controversial presence in the cast of La Goulue (Louise Weber, 1866-1929), the infamous Cancan dancer immortalized by Toulouse-Lautrec.

Yet, on the Boulevard de Rochechouart, all was not in the pink at the "pink circus" (as the circus chronicler Serge would later dub it, referring to its warm color scheme, of which he was particularly fond). Louis Fernando’s financial situation was becoming increasingly unmanageable. As much as he was attached to the circus that had made him famous, Medrano was, from his position as Régisseur Général, well aware of Fernando’s troubles, and he couldn’t see a bright future for himself in his company; in May, at the end of the season, Geronimo Medrano left the Cirque Fernando. In August, Boum-Boum debuted at the Nouveau Cirque, rue Saint-Honoré.

Fernando’s Decline

With Medrano’s defection, Fernando had indeed lost one of its main drawing cards. Although Boum-Boum Medrano did well as a clown at the Nouveau Cirque, he was outshined by George Foottit, who began to team up regularly with the Black augusteIn a classic European clown team, the comic, red-nosed character, as opposed to the elegant, whiteface Clown. Chocolat; together, Foottit & Chocolat will become the Toasts of Paris, and remain so for a full decade. But Medrano had made a good move: In 1892, Raoul Donval, the Nouveau Cirque’s new director, who appreciated Geronimo’s many talents, gave him the position of Régisseur Général—the same position he had held for Louis Fernando, but this time in a much healthier financial environment.

As for Louis Fernando, he had a huge success the same year with his politico-military pantomimeA circus play, not necessarily mute, with a dramatic story-line (a regular feature in 18th and 19th century circus performances)., Les Marins de Cronstadt, but he flopped soon after with a comic pantomimeA circus play, not necessarily mute, with a dramatic story-line (a regular feature in 18th and 19th century circus performances)., Robert Macaire, which he kept nonetheless on the bill for two months—which suggests that he had nothing else to offer. Nonetheless, Fernando’s programs remained by and large attractive, with their usual mix of novelty acts and comic pantomimes, which still competed effectively with the traditional equestrian fare of the Franconis’ Parisian circuses.

To make matters worse, Jeanne Fernando died on May 8, 1894 from a "terrible disease," which may have been tuberculosis—for which there was no cure at the time, and the frightening name of which, like cancer, was always hushed up. Jeanne was only thirty-six, and Louis Fernando was devastated. He closed his circus and rented the building out for a season of operettas; the circus took the name of Théâtre Parisien. It finally reopened as a bona-fide circus in December with the Troupe Rancy-Loyal in a show originally produced by Alphonse Rancy in his resident circus at Lyon. Louis Fernando was nowhere to be seen.

The Rancy-Loyal Troupe occupied the Cirque Fernando, renewing its shows regularly, until the spring of 1895. Then the circus was again rented out for a summer season of variety, and took the name of Concert d’Été. Finally, at the end of the summer, it was completely refurbished, equipped with theater seating and a coco mat in the ring, as in the Nouveau Cirque, and reopened at last in September 1895 under Louis Fernando’s management. In spite of commendable programs that were renewed each Wednesday, Louis Fernando had a hard time trying to bring back his public; he even had to lower his price of admission.

By then, the Banque Boulley et Cie, his bank, had long realized the security they had inherited from the Fernandos’ original dealings. On October 25, 1897, the new owner of Fernando’s circus building, who obviously had not been paid by his tenant, announced that the entire property, land and walls, would be auctioned off: His tenant, Louis Fernando, had staged a moonlight flit. The press mentioned the upcoming sale in early November. What exactly happened after that point is unknown; the sale, if any, was not publicly reported. In any event, the circus was closed and left with a sign on its door: "For Rent."

It was much later discovered that Louis Fernando had remarried, with Marie Vennekens, on October 3, 1897 in Courbevoie, a Paris suburb, a short time before the announcement of his circus’s sale; after her death, he married a third time, on October 28, 1900, with Estelle Ganthey. Louis Fernando then disappeared from the public eye—and from the circus scene. No one noted his death in Paris on February 26, 1917; he had lived at the time rue Danrémont, not far from Montnartre. The Fernando-Beert tomb at the Cimetière de Montmartre mentions only his wife, Jeanne, and their son, Gabriel. His mother and stepfather had long retired to Bruges, Belgium, where Fernando Beert passed away on December 30, 1902.

Thus, by November 1897, the saga of the fabled Cirque Fernando had finally come to an end. Or had it?

LE CIRQUE MEDRANO (1897-1962)

Geronimo Medrano, like everyone else in the circus world, had followed the disturbing disintegration of the Cirque Fernando—but to him, the announcement of its demise hit closer to home. He had spent fifteen years with Fernando, saw the circus building come up, and he became famous in its ring; aside from Louis Fernando, no one had had more to do with its success than Medrano. For seven years, as its Régisseur Général, he had also managed its daily operations. He knew this circus inside out. Geronimo Medrano had just managed Raoul Donval’s short-lived Hippodrome du Champs de Mars (1894-1897), on the Avenue Rapp; he was approaching his fifties, and he thought it was perhaps time to move ahead…

"Boum-Boum" Medrano, Circus Director

All of a sudden, in December 1897, it was announced that Geronimo Medrano was the new tenant of the circus on the Boulevard de Rochechouart, which he had renamed Cirque Medrano. Medrano, well aware that time was of the essence if he wanted to take hold of the vacant Cirque Fernando, had moved swiftly. In order to secure a long-term lease (the annual rental price was 40,000 Francs, about €128,000 today), he had enrolled his old friend Emilio Maîtrejean, a retired acrobat and daredevil (and the son of the former Régisseur of the Cirque Napoléon), who had put his savings at Geronimo’s disposal.

Financially the operation could have been risky, as the Fernandos’ misadventures had shown all too well, especially since Medrano didn’t have time to secure any other backing source. However, two factors had swayed his decision: Firstly, the Cirque des Champs-Elysées was moribund and the Cirque d’Hiver was declining, which limited serious competition to the Nouveau-Cirque; more consequential, Chamberlin, the photo studio that occupied the spaces framing the circus’s façade, was the tenant of the circus itself, not of the property’s owner, and Medrano would therefore collect Chamberlin’s rent—the amount of which was about 40,000 Francs a year.… Geronimo signed a deal with the proprietor without much vacillation and moved his quarters into the circus building’s apartment!The press had been glad to spread the good news, enthusiastically wishing success to the new director. Unlike Louis Fernando, whom they had often derided as a snob and a social climber, the happy, genial, outgoing "Boum-Boum" Medrano had an excellent reputation among Parisian journalists and critics, and of course among the old Cirque Fernando’s aficionados. The fact that the defunct Cirque Fernando was now Medrano’s circus seemed to everybody a logical conclusion. And as everybody knew, a circus that bore the name of Medrano could only be a joyous circus.

Thus the Cirque Medrano opened its doors on December 22, 1897 to an enthusiastic audience—neighborhood habitués and the usual crowd of Parisian cognoscenti, journalists, and artists of all species. The General Manager was Emilio Maîtrejean, and the company for the season included the Fratellinis—that is to say, the remarkable somersaulter on horseback François Fratellini, his brothers, the clowns Luigi and Paolo (Louis and Paul), and The Gentlemen, the eccentric acrobatic and musical act performed by Albert and François. Not yet the fabled clown trio (which would form after Louis’s death in 1909), the Fratellini brothers had nonetheless sowed the seeds of a long association with the Cirque Medrano.

There were other clowns in the program, notably Alexandre Pierantoni, formerly of the Nouveau Cirque, "and his augusteIn a classic European clown team, the comic, red-nosed character, as opposed to the elegant, whiteface Clown.", and comic pantomimes would often be part of the fare—the first of which was titled Le barbier fin-de-siècle ("The End-of-Century Barber"). Geronimo Medrano, however, was not performing as a clown anymore: He was now a Circus Director, and would only appear sporadically holding the chambrière(French) Long whip customarily used by Equestrians for the presentation of horses "at liberty." (the Equestrian Master’s long whip), but the show bore his distinctive, joyful stamp. Like its predecessor, the Cirque Medrano gave priority to novelty acts and comedy, and it changed its program partially every week, with performances every night, and matinees on Thursdays, Saturdays, Sundays, and Holidays.

Geronimo Medrano maintained the old open-door policy that Mrs. Fernando had originated for the neighboring artists. The establishment of the legendary Bateau-Lavoir as an artists’ communal house in Montmartre at the turn of the century would bring another generation of upcoming artists and painters to the Cirque Medrano: Pablo Picasso, Juan Gris, Georges Braque, Henri Matisse, Kees van Dongen, Jean Cocteau, Guillaume Apollinaire, to name but a few. Like their predecessors, they helped keep in the limelight the already fabled "cirque montmartrois" (circus of Montmartre).

Unlike the ambitious and carefree Fernando, Medrano was fiscally conservative. He also knew how to attract good acts at a reasonable price: He was well known and had a good reputation in the business, and his cheerful personality was hard to resist. The circus had shown a positive balance sheet at the end of 1898. In 1899, its gross income had increased by 123,534 Francs. After Fernando’s never-ending financial quandaries, Medrano’s landlord was finally able to put his mind at rest. Meanwhile, that same year, Charles Franconi closed the venerable Cirque des Champs-Elysées, which had once been Paris’s most fashionable circus.A new Hippodrome opened its doors in May 1900 on the Place de Clichy, not very far from Medrano. It was supposed to take advantage of Paris’s Exposition Universelle (World Fair) of 1900, but the Fair didn’t prove a boon for Parisian circuses. A huge arena designed for equestrian spectaculars, the Hippodrome was perhaps too big to be profitable: it would eventually close in 1907. (It was transformed into Europe’s largest movie house, the Gaumont Palace—the Parisian equivalent of New York’s Radio City Music-Hall.) In 1906, another circus was built on Paris’s Left Bank, Avenue de la Motte-Piquet, the cavernous Cirque Métropole, which would also suffer from its sheer size, but would remain active with various ups and downs until 1930. And there were still, of course, the Cirque d’Hiver and the Nouveau Cirque.

Paris had become, and would remain until the 1950s, Europe’s circus capital. In spite of heavy competition, the Cirque Medrano held its own without a flinch, and whereas all its competition would have dark interludes and turn into movie houses or theatres at times, Medrano never ceased being a circus. It had qualities that its rivals couldn’t truly match: Its warmth and intimacy, a lack of pretension that reflected well the personality of its beloved founder, a great variety of offerings, clowns who were allowed to shine in an environment that perfectly suited them, and perhaps for all these reasons, it had fierce supporters. Soon, the circus on the Boulevard de Rochechouart became known simply as "Medrano": Parisians used to "go to Medrano"—a household name that had grown to be synonymous with Circus and didn’t need qualifiers.

Change Of Guard

On July 5, 1892, while he was still working at the Nouveau Cirque, Geronimo Medrano had married Charlotte Blanche Lippold (1854-1905). They formed a strong couple, even though Blanche was barren and didn’t give Geronimo an heir. On August 18, 1905, at age fifty-one, Blanche Medrano passed away, rather suddenly; Geronimo was devastated. He was fifty-six years old (at a time when the average life expectancy for men was around fifty years), he had no successors, and he felt his life had suddenly become pointless. Yet he had a solid support system in his close friends at the circus: The faithful Emilio Maîtrejean, Thomas Hassan, his Régisseur, and "Mr. Emile" (Émile Laurent) his comptroller. They helped him go through a very difficult period.

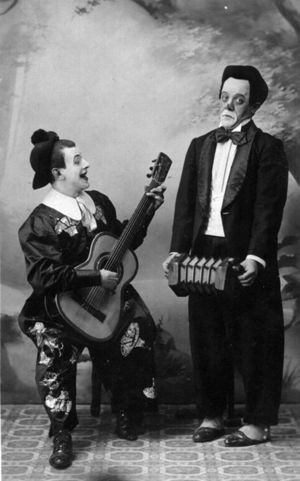

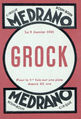

His circumstances brightened up in early 1906, when Geronimo found a warmhearted confidante in Berthe Perrin (1876-1920), a thirty years old seamstress who was twenty-five years his junior. Their friendship eventually developed into an affair and, on May 18, 1907, Berthe gave birth to a son, Jérôme (1907-1998). The Medrano line was finally revived, and Geronimo was elated. He married Berthe on August 28, and legitimized his son on the occasion. By all accounts, Berthe was a sweet, caring person, but her humble origins and hard life had made her a strong woman who knew how to take care of business. Although she was not a circus person, Berthe Medrano proved to be a good partner to Geronimo.In 1908, Medrano hired a new clown duet, Antonet & Grock. Grock had replaced Antonet’s previous partner, the celebrated and immensely creative Little Walter, whose appearance Grock had copied to perform the musical entrée(French) Clown piece with a dramatic structure, generally in the form of a short story or scene. Walter had created with Antonet. The piece, with some additions and much stretching, will make Grock a star. The following year, Louis Fratellini died in Warsaw from a smallpox epidemic, and his brothers, François, Paul and Albert joined forces and formed a clown trio to help support Louis’s widow and large brood. Although these two names, Grock and Fratellini, will long be associated with Medrano, the circus’s stars were then the talented and popular Spanish clowns Rico and Alex Briatore, who were featured on the Boulevard de Rochechouart from 1910 to 1914.

As Parisians’ favorite clowns, Rico & Alex had successfully supplanted the Nouveau Cirque’s Foottit & Chocolat, whose association was coming to an end. As a matter of fact, Medrano was now the Parisians’ circus of choice. The Cirque d’Hiver had been converted into one of Paris’s worst movie houses in 1907; this was followed for a few months, at the beginning of 1908, by the Cirque Métropole, although it quickly re-opened as a bona-fide circus under a new management (and a new name: Cirque de Paris). As for the Nouveau Cirque, it had begun its long decline. Medrano had dealt smartly with the emerging success of the cinematograph: From 1912 until the end of World War I, its programs ended with a short projection of the "American Vitograph" (sic)—which morphed into the "Medranograph." Other acknowledgement of changing times: Geronimo had installed electric lighting.

Although everything was looking good for his circus, it was not the same for Geronimo Medrano. Sometime in late 1910, he had a stroke that left him partially paralyzed. Nonetheless, he bravely continued running his circus until April 27, 1912, when he died suddenly of an attack of uremia; he was sixty-two, and his son, Jérôme, who sadly had had very little time to know his father, was only five years old. Geronimo had bequeathed the Cirque Medrano to him.

Berthe Medrano’s Circus

Geronimo "Boum-Boum" Medrano was inhumed near his first wife, Blanche, after whose death he had commissioned a mausoleum at the nearby Cimetière de Montmartre. A large crowd accompanied him to his last resting place. As for Berthe Medrano, she was intent on preserving their son’s inheritance; without hesitation, she took over the management of the circus that bore her and her son’s name. She left to her late husband’s associates, Emilio Maîtrejean and Thomas Hassan, the care of running the circus’s day-to-day operation, and asked a former acrobat whom she trusted, Rodolphe Bonten (1869-?), to help her cast the shows. As for the circus’s finances, she took full control. To make things clear, five-year-old Jérôme Medrano, dressed in the traditional blue uniform of the régisseurs, appeared at the ring entrance at some matinees.Berthe Medrano proved a good administrator, and the team that surrounded her was indeed very competent. Business was still going strong. In 1912, the year of Geronimo’s death, the Cirque de Paris had closed again and become a theatre-cum-boxing arena. The political situation in Europe was tense; Kaiser Wilhelm II of Germany was posturing aggressively, and Parisians, who had not forgotten the war of 1870, were on edge. In September 1913, the Nouveau Cirque began its season with matinees only, three days a week, Thursday, Saturday and Sunday. In October, the Cirque de Paris, now known as Le Palace, morphed once again into a movie house. Yet Medrano was still doing well, in spite of the fact that Emilio Maîtrejean, who had been instrumental in its success—and indeed its very existence—had decided to retire, to everybody’s chagrin.

In the spring of 1914, Rodolphe Bonten hired the new clown trio of François, Paul and Albert Fratellini, who had just been featured with great success at Circo Parish in Madrid. They didn’t stay long: On June 28, a young Serbian who was a Yugoslav nationalist assassinated the crown prince of Austria-Hungary, the Archduke Franz Joseph; Austria declared an ultimatum to Serbia, which supported Yugoslavism (the movement for a South Slavic national identity); on July 28, the Austrian army invaded Serbia, which, owing to the intricate web of European alliances, triggered World War I. On August 3, Germany, Austria’s main ally, declared war to France; Paris’s circuses and theatres closed their doors. The Fratellinis returned to Circo Parish, along with Rico & Alex.

In December 1914, the Nouveau Cirque reopened. Most theatres, however, remained closed until the beginning of 1915. Then, little by little, they came back to life, including Medrano. Casting the shows had become difficult since a large number of male performers had been drafted, and although the circus is international by essence, the situation made it impossible to tap into the large reservoir of performers from countries that happened to be at war with France.

Like the majority of their colleagues, the Fratellinis disliked William Parish, the owner of Madrid’s Circo Parish (the old Circo Price), and they let Bonten know that they were available and ready to come back to Paris. Between the three of them and their late brother Louis, they had a large family to support, and their nationality was perhaps a little too difficult to sort out (Paul was born in Sicily, François in Paris, and Albert in Moscow): They were exempt from military service. Bonten jumped on the opportunity.The Fratellinis were not only extremely talented, they also offered something new: A clown trio. Until then, clowns had worked solo, or as a clownGeneric term for all clowns and augustes. '''Specific:''' In Europe, the elegant, whiteface character who plays the role of the straight man to the Auguste in a clown team./augusteIn a classic European clown team, the comic, red-nosed character, as opposed to the elegant, whiteface Clown. team, like Foottit & Chocolat and many others after them. To the traditional duet of François (the clownGeneric term for all clowns and augustes. '''Specific:''' In Europe, the elegant, whiteface character who plays the role of the straight man to the Auguste in a clown team., charmingly light and graceful) and Paul (a ridiculous and bombastic augusteIn a classic European clown team, the comic, red-nosed character, as opposed to the elegant, whiteface Clown.), they had added Albert, who had developed an extravagant and phantasmagoric augusteIn a classic European clown team, the comic, red-nosed character, as opposed to the elegant, whiteface Clown. character that injected a good dose of mirthful surrealism in everything the brothers did. Additionally, they had a vast repertoire of classic entrées and musical interludes to which the unusual composition of their team—and their imagination—added a veneer of novelty.

At a time when Parisians needed to escape the daily reality of a war with no end in sight, Medrano was the place to go: It always had good clowns to bring smiles on anyone’s face in a warm and familiar atmosphere—but the Fratellinis delivered even more: A total escape into a hilarious world of pure fantasy. They quickly become the talk of Paris, and Medrano being the circus it was, journalists, artists, writers, and Paris literati in general transformed the trio into stars of first magnitude. In time, Fernand Léger and a host of painters immortalized them, journalists chronicled their every move, writers wrote essays and books about them, their likeness was used in advertising, and their fame eventually (after the war) crossed the borders. Medrano collected the fruits of their glory.

The Bonten Era

When World War I came to an end on November 11, 1918, Medrano entered an era of great prosperity. The Cirque d’Hiver and the Cirque de Paris were inactive, and the Nouveau Cirque was desperately trying to survive. Medrano had become "Le cirque de Paris" ("Paris’s own circus"), a label it will keep as its slogan until the end. In 1918, Fernand Léger (1881-1955) created his neo-cubist painting Le Cirque Medrano, the first of a series of works on the circus. The Fratellinis were still Paris’s enfants chéris (favorite children), and they still attracted crowds to the Boulevard de Rochechouart; habitués returned every week to see what new entrée(French) Clown piece with a dramatic structure, generally in the form of a short story or scene. these very imaginative clowns were going to offer.

Yet all was not well. Berthe Medrano was ill; she was diagnosed with cancer. In January 1918, she transferred the management of the circus to her faithful and capable right-hand man, Rodolphe Bonten, and went to rest in a villa she had bought in Nice, on the French Riviera. Jérôme was eleven, and she had to secure his education and his future: The circus was his, and Berthe wanted to ensure that it would remain so. Upon her return to the capital, she had a long discussion with Bonten. On June 20, 1918, Rodolphe Bonten and Berthe Medrano were married in the 9th Arrondissement's City-Hall of Paris. It was indeed a marriage of convenience: Rodolphe, as Jérôme’s stepfather, would become his legal guardian, and for the time being, with or without Berthe, the Cirque Medrano would remain a family affair.Rodolphe Bonten was basically a honest man, devoid of ostentation and personal ambitions, and a capable director. Artistically, he was not overly imaginative, but he knew what worked for Medrano, and the circus continued to flourish under his reign. His only flaw, according to Louis Merlin, who was an habitué of Medrano, was his habit to play nervously with the coins in his pants’ pockets each time he watched an attractive female performer in the ring. If he had a good eye for pretty girls, he also had a good eye for outstanding acts—as well as for clowns: Beside the Fratellini, such legendary clowns as Antonet & Béby, the Dario-Barios, Porto, and Rhum came to grace Medrano’s ring under his tenure, and became bona-fide stars of the Parisian circus.

Medrano had become such a famous name around Europe that, in 1920, the Austrian director Ludwig Swoboda renamed his Zirkus Lajos, Circus Medrano aus Wien ("Vienna’s Circus Medrano"). Since there were no trademark agreements at the time between European countries, Medrano eventually became a household name in Austria—and in Eastern Europe, where Swoboda's circus traveled—and eventually in Italy when Swoboda's title was eventually bought by the Casartelli family in 1972.

Berthe Medrano finally passed away on August 30, 1920, leaving to Rodolphe Bonten the responsibility of the circus—and of her son, who was orphaned at the age of thirteen. Berthe was buried near Geronimo at the Cimetière de Montmartre, and Bonten became de facto Jérôme’s tutor; to his credit, he made sure that Jérôme receive an excellent education in the best possible schools. Bonten also took Jérôme on circus trips during school recesses, but although they both lived in the circus’s apartment and Jérôme was thus immersed into circus life, Bonten didn’t try to involve him in any aspect of the circus’s affairs. Like many kids orphaned in adolescence, Jérôme resented a stepfather that only fate had imposed on him—and who apparently didn’t provide him with the kind of parental affection and interest he craved.

Yet, Bonten ensured that Jérôme’s circus continued to thrive. In 1921, the Cirque de Paris reopened at last as a circus under a new management. In 1923, Gaston Desprez took the lease of the Cirque d’Hiver, and revived it successfully as the major circus it had been. Then, in 1924, Oscar Dufresne and Henri Varna transformed the large Théâtre de l’Empire into a "Music-Hall Cirque", a variety house with an emphasis on circus acts, on the model of the famous Wintergarten variety theatre in Berlin. There were now five active circuses in Paris (if one includes the Empire, which was playing on the same turf). Although the Nouveau-Cirque and the Cirque de Paris didn’t present a big threat to Medrano, the Cirque d’Hiver and the Empire quickly became serious contenders. Medrano still had the Fratellinis, who had a huge success in 1923 with a comic pantomimeA circus play, not necessarily mute, with a dramatic story-line (a regular feature in 18th and 19th century circus performances)., Les tribulations d’un travailleur ("A Workman’s Trials")—but not for long.

At the end of the 1924 season, the Fratellinis asked Bonten for a raise. Bonten made a very ill-advised move: He refused to change their contract; Gaston Desprez jumped on the opportunity and offered them what they asked and more: He made them Artistic Directors of the Cirque d’Hiver—a purely honorific title, but which was very good publicity. Although the Fratellinis wouldn’t find at the Cirque d’Hiver the type of audience they had had at Medrano (in terms of quality and prestige), they were nonetheless extremely popular, and Desprez had realized a major coup. Bonten saw the evidence of his mistake at the beginning of the 1924-1925 season when Medrano’s box office receipts showed a significant decline.Some relief came in April 1926 when the ailing Nouveau Cirque finally shut down—although its closing probably profited the Cirque d’Hiver more than Medrano. Meanwhile, Jérôme Medrano was doing his mandatory military service at Saint-Cyr l’École, near Paris. The following year, Grock was starring at the Empire (he had long left the circus ring for the much more lucrative variety stage), while Medrano launched two new clown trios, the Dario-Barios, who had adjoined to their group the remarkably talented augusteIn a classic European clown team, the comic, red-nosed character, as opposed to the elegant, whiteface Clown., Rhum, and Cairoli, Porto & Carletto. Medrano was still the ideal place to showcase talented clowns, and if it had lost the Fratellinis, the circus had a faithful audience that truly appreciated good clowning—which the Dario-Barios and the Cairolis indeed delivered—and still filled its seats to have a good time.

Then, on May 18, 1928, Jérôme Medrano reached his majority. He had previously claimed to wish to continue his studies and become a Merchant Navy officer. But suddenly everything changed, rather drastically. On June 4, to everyone’s surprise (Jerôme himself admitted later that it was on a whim), he married the beautiful Rachel Baquet, whose father had worked for the Cirque Palisse in a managerial capacity and owned a café near the circus; Mr. Baquet was also in charge of Medrano’s bar and concessions.

Finally, just ten days later, on June 14, 1928, Jérôme Medrano took officially possession of his circus, and dismissed Rodolphe Bonten, to whom he offered a generous severance pay. Bonten, certainly a little shaken, disappeared from the circus scene. Before anyone could take a breath, Jérôme was fully in charge and the Cirque Medrano was entering a new era. He made his new wife, Rachel, co-director (she too had been born into the circus, and her family could lend some help) and the press dubbed the young couple, "Europe’s youngest circus directors."

Enter Jérôme Medrano

Along with Bertram Mills and his sons Cyril and Bernard in England, John Ringling North in the United States, and before them, Hans Stosch in Germany, Jérôme Medrano belonged to an unconventional breed of circus directors that had received a solid academic education, and whose cultural interests and social connections expanded outside the circus world—but who showed a genuine enthusiasm for the circus that was triggered by a mixture of vested interest and artistic inclination. They would change the image of the circus in their respective countries and beyond.

Jérôme Medrano inherited a business in good shape, artistically successful and fiscally stable—conditions for which Berthe Medrano and Rodolphe Bonten can be commended. Notwithstanding the fact that he had spent his childhood and most of his adolescence within the walls of his circus, Jérôme didn’t know much about its day-to-day management—although he was of course quickly made aware of the peculiar situation of its physical ownership. Even so, Jérôme set about working and began by honoring all the contracts signed by his stepfather for the upcoming season (which included, as usual, some of the best artists—and clowns—in the business).Jérôme would have a hard time, however, coming to terms with Bonten’s foolish dismissal of the Fratellinis, whom he had known since childhood, and was not adverse to giving it as a good reason for his stepfather’s dismissal. Meanwhile, he surrounded himself with a mixture of old Medrano collaborators, such as Thomas Hassan, the circus’s Régisseur, and newcomers such as the well-known journalist and circus chronicler André Legrand-Chabrier, who, as Secrétaire Général of the circus, took over Press and Public Relations. The latter’s appointment to a key position that was customary in Parisian theatres but not in the circus was the first sign of a new managerial style.

Unlike most of his circus colleagues, who relied heavily on agents to find new talent, Jérôme Medrano would regularly visit Europe’s and America’s major circus and variety shows, and do his own talent search. In January 1929, as the Medrano season ran steadily on its rails, Jérôme and Rachel Medrano went to Berlin to visit the famous WinterGarten, where some of the best circus and variety acts of the time could be seen. Then they made a stop in Gottingen to see the fabled Circus Sarrasani and meet with its legendary director, Hans Stosch-Sarrasani. The giant German circus’s innovative organization, its technical achievements, and its spectacular show duly impressed the Medranos. After his visit, Jérôme was in the opinion that Sarrasani was perfection, the model after which all traveling circuses should be run. His discovery of Sarrasani would serve him later.

After the end of the 1928-29 Season in June, the circus building was entirely refurbished. Everything was painted anew, and Barbier-Daumont, a decorator well known in the theatre community, painted a series of frescoes on the periphery of the house, which depicted scenes of the life of traveling circus folks. Jérôme had also four cabins installed on the lower roof of the building to house spotlights and their operators, and a fifth one was installed in the foyer, where the projector of the old "Médranographe" used to be. Julien Pavil (1897-1952) was commissioned two large paintings: the first one, representing traveling entertainers parading on a fairground stage, welcomed the guests in the entrance lobby; the other one, picturing Paris’s most famous circus and variety critics, was displayed behind the new bar installed backstage.

When the circus reopened on September 9, 1929, its program had been entirely conceived by Jérôme Medrano. It was a true Parisian event attended by the Tout-Paris—journalists and major critics, press and industry magnates, theater stars and producers, renowned novelists and authors, publicity-hungry politicians, and everyone else with a name. The show featured a bounty of remarkable acts, including a spectacular ten-person bar-to-barA flying trapeze act in which flyers leap from a trapeze to another, instead of from a trapeze to a catcher as is most commonly seen today. flying actAny aerial act in which an acrobat is propelled in the air from one point to another. on two porticos placed in cross, created especially for Medrano by Edmond Rainat, and an eighteen-horse liberty"Liberty act", "Horses at liberty": Unmounted horses presented from the center of the ring by an equestrian directing his charges with his voice, body movements, and signals from a ''chambrière'' (French), or long whip. act presented by Ernst Schumann. The clowns were Ilès & Loyal, and the trio Caïroli, Porto & Carletto, who had just signed a long-term contract.

At the end of the evening, in the ring, Thomas Hassan was made Officier de l’Instruction Publique (which has thankfully been replaced since by the Ordre des Arts et Lettres, a more suitable distinction!). It was indeed a night to remember: Jérôme’s "New Medrano" was launched!

Medrano’s Golden Age

Jérôme Medrano’s revamped circus emerged as a contemporary place of entertainment, where a fast-paced show with top-shelf acts was presented in the best possible light—which can be taken literally, since acts were often isolated in spotlights instead of being presented in full light, as had been the norm since the gas chandeliers. Of course there were some old-timers who waxed nostalgic, complaining that the circus had lost its original atmosphere and the show looked like a music-hall (variety) production instead of the age-old circus presentation they had expected. Yet this change of style was precisely what brought back around Medrano’s ring a new, younger and more sophisticated audience that had hitherto shifted its interest from the circus to the more fashionable variety stage.

Jérôme Medrano, who had spent time among the well-educated and affluent youth of his generation (notably at the exclusive École des Roches), was well aware of this shift. He also intended to bring back to Medrano top circus acts that had deserted the ring for the comfortable and lucrative varieties. The clown Grock, who had learnt most of his craft at Medrano and whom Jérôme had known since childhood, had become a major international star on the variety circuit—a status among clowns that only the Fratellinis had acquired in the circus ring, albeit without the financial rewards. Working now exclusively on stage, Grock had become a wealthy man, and several other top performers made a much better living in variety theatres than they had done in the circus.Jérôme had not been raised as a circus insider, taught to believe in the circus world’s unspoken law proclaiming that artists should accept relatively low wages if they wanted work and, more often than not, harsh working conditions. Top circus acts that could work for more money and in more comfortable surroundings in variety theatres had obviously ceased to believe in these old tenets, a fact Jérôme had indeed noticed—even though some of his more "circus-savvy" colleagues had not. In February 1930, he signed his first contract with Grock, offering him the price and conditions he had enjoyed at the Empire, where he had appeared regularly as a headliner. It was an expensive proposition, but Grock’s act was about forty minutes long, which would have required four or five individual acts to replace anyway—and his name alone was sure to sell tickets.

Grock was very much in demand all over Europe, so his Medrano debut had to wait until January 1931. Although Grock’s agent was his brother-in-law, Dante Ospiri, negotiations had been held on a very personal level between Jérôme and Grock. Nonetheless, Jérôme had appreciated Ospiri’s business style, and hired him as Medrano’s booking agent. In April 1930, the great Portuguese equestrian Roberto de Vasconcellos was featured at Medrano. Vasconcellos, who was new to the circus, didn’t like to handle his own engagements, and he signed a ten-year contract with Jérôme, in effect making him his exclusive manager and agent. At the outbreak of WWII, Jérôme would send Vasconcellos to Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus in the United States, where the famous equestrian became a long-time fixture.

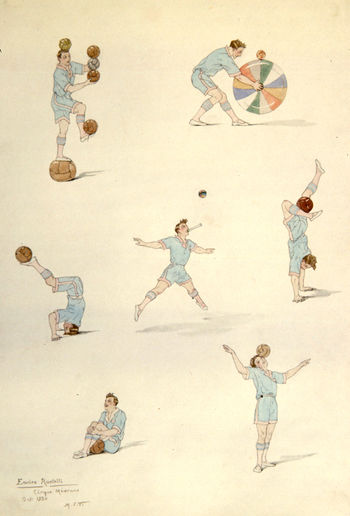

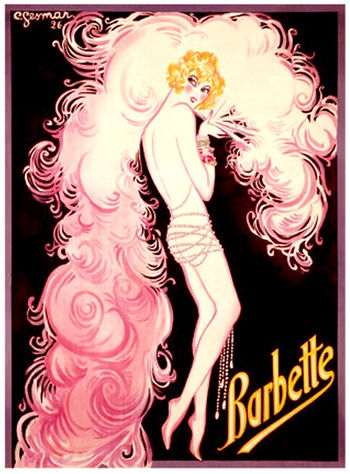

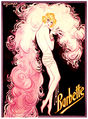

The 1930-31 Season opened with the return to Medrano of the clowns Antonet & Béby, and in October, the world’s greatest juggler, the legendary Enrico Rastelli, was the star of the show for the next five weeks. Although he was born in a circus family, the phenomenal Rastelli had long switched to the variety stage, where he enjoyed top-billing—and top money. It was the first time he had appeared in a circus ring in France. Medrano’s always-efficient press department made it an exceptional event, and crowds filled the seats to see Rastelli in the ring. Jérôme immediately signed him for a return engagement the next season. Another coup was, in December, the first appearance in a circus ring of the American transvestite trapeze and tight-wire artist Barbette, one of the brightest and most talked-about stars of the variety stage, who was all the rage then, and the darling of Paris’s homosexual elite led by Jean Cocteau. Meanwhile, in June 1930, the ailing Cirque de Paris shut its doors for the last time.

Grock made at last his first star appearance at Medrano in January-February 1931 ("For the first time on a circus ring in 23 years!" said the printed program), selling out for his full run of five weeks. Jérôme’s policy was proven right: He made a good profit in spite of the cost of hiring such expensive variety acts, and, most importantly, he brought to his Parisian circus a new audience that found at Medrano the same quality of presentation they experienced in the best variety theaters. They discovered in the process clowns and other variety acts they had never seen on stage, some of whom they quickly adopted as their new favorites. Jérôme was creating a modern-day following as well as a fresh crop of circus stars.

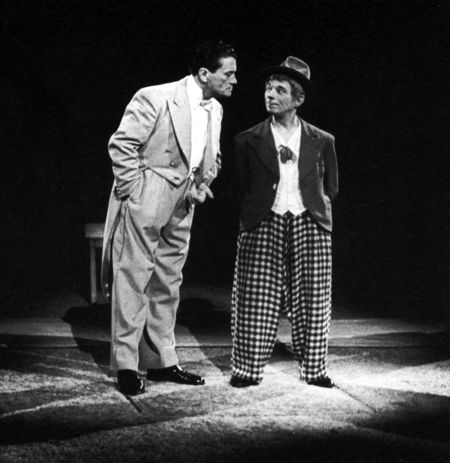

The 1931-32 season also saw the debut of Georges Loyal as Régisseur de piste (Ringmaster); he would remain at Medrano until 1939. Over the years, there had been several members of the vast Loyal family acting as Régisseur in various Parisian circuses, and somehow, "Monsieur Loyal(French) The régisseur or presenter of the show in a French circus. So called because of the many members of the Loyal family who occupied this position brilliantly in Parisian circuses." was often cited as an ideal illustration of the traditional Ringmaster. However, this was Medrano: The Régisseur was more than a Ringmaster and a presenter; he was the clowns’ straight man, and for eight long years, all Medrano’s star-clowns—and they were many—interacted with Georges Loyal in the ring, respectfully addressing him, of course, as "Monsieur Loyal(French) The régisseur or presenter of the show in a French circus. So called because of the many members of the Loyal family who occupied this position brilliantly in Parisian circuses.." The name, which already defined the function, finally stuck to it—to such an extent that, in time, all French ringmasters became known as "Monsieur Loyal(French) The régisseur or presenter of the show in a French circus. So called because of the many members of the Loyal family who occupied this position brilliantly in Parisian circuses.," and the term Monsieur Loyal(French) The régisseur or presenter of the show in a French circus. So called because of the many members of the Loyal family who occupied this position brilliantly in Parisian circuses. has become today the French generic term for Ringmaster.Everything was going well, but Jérôme was concerned by the situation of his circus building, of which he was still just the tenant—albeit without any constraints as long as he paid his rent. At some point, the circus had become the property of the Saint family, a rich and powerful family of French industrialists that ran the Saint Frères company, France’s foremost hessian manufacturers, makers of ropes, canvas covers, tarpaulins, tents and even circus big tops. Roger Saint, who was in charge of the family’s holdings, informed Jérôme that the property was divided between members of the family, most of whom, satisfied with the steady income it provided, were unwilling to sell. Since the rent was relatively low, and the family was in no way interfering in his business, Jérôme had to be content with the situation.

In May of 1930, Jérôme Medrano made his first trip to New York, where he met up with his closest friend, Maurice Chevalier, the popular French singer who had become a Hollywood film star. They visited Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus, which was showing at Madison Square Garden; there, Jérôme met John Ringling North, a future circus director of his generation and with a similar background. For years to come, there would be a constant flow of acts between Medrano and Ringling. Then Chevalier took Jérôme to Hollywood, where Jérôme (who was a huge cinema enthusiast) established contacts he would use later. Meanwhile, in August, a new lighting system was installed in the circus, including modern projectors affixed on the columns around the house, equipped with rolling gels that allowed changing their color automatically. It was true theatrical lighting, hitherto unheard of in the circus world.

Then, during a scouting trip to Italy in 1931, Jérôme discovered a little-known Italian circus family whose members were exceptional equestrians, able to present a large variety of acts. He signed the Cristiani family for the entire 1931-32 Season. John Ringling (or his gants) saw them there, and two years later, the Cristianis went to work with Ringling Bros. in the United States, where they settled and eventually created their own circus. That season also saw the emergence of the augusteIn a classic European clown team, the comic, red-nosed character, as opposed to the elegant, whiteface Clown. Rhum as a major clown star, and the tight-wire somersaulter Con Colleano made a profound impact and became the new talk of the town. The Andreu-Rivels, with Charlie Rivel’s impersonation of Charlie Chaplin on the flying trapezeAerial act in which an acrobat is propelled from a trapeze to a catcher, or to another trapeze. (See also: Short-distance Flying Trapeze), were another hit that season. At the end of February, Medrano presented a revue, La Revue de Medrano, with music by Maurice Yvain (1891-1945), which ran successfully for five weeks, before the return of Grock in April. It was a very good season.

Innovations And Expansion

In September 1932, Jean Coupan left the Cirque d’Hiver and replaced André Legrand-Chabrier as Medrano’s Secrétaire Général: For someone of Coupan’s imagination and energy, Medrano was indeed the place to be. The new season was one of innovations. It saw the creation of the Club des Amis de Medrano (Friends of Medrano Association), the embryo of a circus school for children aged eight and up, which proved very popular. The well-known circus collector Maurice Thomas-Moret organized exhibitions of rare prints and objects from of his outstanding collection in the circus’s foyer.

Medrano’s printed program became a magazine, with articles chronicling the circus and the major artists of each new show (which was now renewed every two weeks); Louis Merlin produced a regular radio broadcast from Medrano, mirroring the magazine, with interviews and news. To many circus cognoscenti, Medrano had become an exclusive clubA juggling pin. where they met around the ring, and in the foyer amidst Thomas-Moret’s treasures. Medrano was definitely not an ordinary circus.

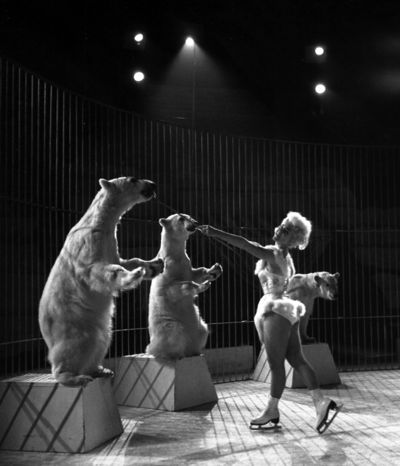

In November, for the first time since the Nouveau Cirque’s demise, Medrano presented a water pantomimeA circus play, not necessarily mute, with a dramatic story-line (a regular feature in 18th and 19th century circus performances)., Le Cirque sous l’Eau, with an army of clowns, beautiful naiades in an aquatic ballet, and a battalion of sixteen showgirls. The pool equipment had been rented from the famous lion trainer Alfred Schneider’s circus in Germany. Le Cirque sous l’Eau ran successfully for three months. The legendary equestrienneA female equestrian, or horse trainer, horse presenter, or acrobat on horseback. Therese Renz (who was seventy-three and had not been seen in Paris since 1900!), the superlative Russian juggler Massimiliano Truzzi, and Con Colleano were among the 1932-33 Season’s highlights.