Difference between revisions of "Barbette"

From Circopedia

(→The Final Years) |

(→The Final Years) |

||

| Line 133: | Line 133: | ||

Vander made other forays in film: He often consulted on circus-themed movies, most notably the film version of ''Jumbo'' (1962). However, his most enduring success in that medium is the work he did for Billy Wilder's comedy ''Some Like It Hot'' (1959), for which he trained Tony Curtis and Jack Lemmon in the subtle art of female impersonation. Billy Wilder had seen Barbette in his heydays in Berlin, and believed he was the best person for the job—although he cautioned Vander not to make his stars look too perfect! | Vander made other forays in film: He often consulted on circus-themed movies, most notably the film version of ''Jumbo'' (1962). However, his most enduring success in that medium is the work he did for Billy Wilder's comedy ''Some Like It Hot'' (1959), for which he trained Tony Curtis and Jack Lemmon in the subtle art of female impersonation. Billy Wilder had seen Barbette in his heydays in Berlin, and believed he was the best person for the job—although he cautioned Vander not to make his stars look too perfect! | ||

| − | Vander thought Curtis had good potential, but he had trouble with Lemmon, whom he considered hopeless. On his end, Jack Lemmon complained that Vander took his task much too seriously. Be that as it may, the film was an enormous hit and has since become a classic—and Lemmon won an Oscar for a part that owed a | + | Vander thought Curtis had good potential, but he had trouble with Lemmon, whom he considered hopeless. On his end, Jack Lemmon complained that Vander took his task much too seriously. Be that as it may, the film was an enormous hit and has since become a classic—and Lemmon won an Oscar for a part that owed a good deal to Barbette's coaching. |

''Disney on Parade'', however, was Vander's last job. It seems that polio eventually caught up with him, in the form of post-polio syndrome, a cluster of potentially disabling symptoms that appear decades after the initial illness. He was living then with his half-sister Mary in Austin, Texas; one day, as he was hanging curtains for her, he fell and couldn't get back on his feet. Despite his immense will and strength, he could no longer move properly and became a crippled man. This he couldn't accept: On August 5, 1973, he committed suicide by overdose. | ''Disney on Parade'', however, was Vander's last job. It seems that polio eventually caught up with him, in the form of post-polio syndrome, a cluster of potentially disabling symptoms that appear decades after the initial illness. He was living then with his half-sister Mary in Austin, Texas; one day, as he was hanging curtains for her, he fell and couldn't get back on his feet. Despite his immense will and strength, he could no longer move properly and became a crippled man. This he couldn't accept: On August 5, 1973, he committed suicide by overdose. | ||

Revision as of 23:51, 13 May 2024

Aerialist, Tightwire Dancer, Act Choreographer

By Dominique Jando

Between 1920 and 1935, the American trapeze and tightwireSee Tight Wire. artist Barbette (1898-1973) was one of the greatest and brightest stars of the international variety circuit, notably in Europe. If he was indeed a talented acrobat, he was also a remarkable female impersonator and his act, which played with great artistry and flair on gender confusion, was and would remain unique.

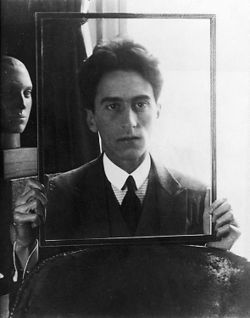

In Paris, where he first became a true sensation, Barbette was feted by the legendary poet, playwright, cineaste, artist and trendsetter Jean Cocteau, who made him the darling of Paris's intelligentsia—notably its gay component—and started his legend. Numerous articles, books, thesis and even a play have been published on Barbette, his act, and his androgyny. The most important publication, Le numéro Barbette, with texts by Cocteau and photographs by Man Ray, dates from 1980—seven years after Barbette's death.

A Texan Childhood

Barbette's childhood information is particularly confuse, but a close look at official documents helps clarifying it enough to avoid pointless speculations. He was born Vander Clyde Broadway on December 19, 1899, in Trickham, a small community in Texas's Coleman County, about sixty miles south of Abilene. His mother was Hattie Broadway, née Martin (1879-1949), a milliner, who was twenty when she gave birth to Vander; she lost her husband, Henry Broadway, the following year: Vander, who was barely one year old at the time, practically never knew his father.

The family moved south to the farm of Hattie's grandparents in Llano, fifty miles from Austin, where the 1900 census gives Vander a young half-brother, Malcom Wilson. Since Hattie was mentioned as Hattie Wilson on Barbette's death certificate, one may surmise that, in 1900, she was in a relationship with a Mr. Wilson, whom she perhaps married soon after. If so, it would have been a short-lived union, since she eventually married in 1906 Samuel E. Loving, who worked in a broom factory, had been a Roughrider with Theodore Roosevelt, was a volunteer fireman, and became a Williamson County Sheriff.

It may be at that time that the family moved south again and settled in Round Rock, a city part of the Greater Austin area in Williamson County—which is often given as Vander's birthplace, although it is just where he spent most of his childhood. Samuel and Hattie would have five children together, two sons and three daughters. One day, Hattie, who was artistically minded, took Vander to see a circus in Austin. Young Vander was particularly impressed by the show, especially by a tightwireSee Tight Wire. act. He was immediately hooked and, then and there, decided that he would become a circus performer.Apparently, Vander began training by himself in wire-walking on a rope installed in the family’s yard, and in gymnastics. It is not known if he ever had a teacher at a point or another, but he became quite an athletic kid. When opportunity arose, he took menial seasonal jobs, like helping in the local cotton picking, and with the money he made, he attended as many circuses as he could. Observing performers at work obviously gave him examples to emulate in his self-training.

It was a time when the American circus industry was still flourishing, and circus was still the country's most popular form of entertainment; hundreds of circuses, big and small, roamed the land. Most major companies visited Austin, and smaller ones often made one-day stands in the area. Their activities, and that of the thousands of performers that graced their many rings, were widely reported by the showbusiness magazine Billboard, of which Vander became an avid reader.

Vander graduated from Round Rock High School in 1913, at age fifteen. It was time for him to find a job and, having made his mind that he would be a circus performer, he immediately began to check the job offers in Billboard. He found an ad posted by one of the Alferetta Sisters—an aerial duet that didn't leave a strong mark in circus history—who had lost her partner and was looking for a new one. The auditions were in San Antonio, Texas, which was not far from Austin, and Vander decided to apply.

Beginnings

In an interview he gave to the New Yorker magazine dated September 20, 1969, Vander gave its author, Francis Steegmuller, some information about the Alferetta Sisters: They had, at the time, a double trapeze and swinging Roman ringsA pair of small wooden or metallic rings hanging from ropes or straps, used by circus aerialists as well as competition gymnasts. act; apparently, one "sister" had died, and the surviving one, who was married to a blackface comedian billed as Happy Doc Holland, the Destroyer of Gloom, needed someone with whom to rebuild her act. (From "Alferetta, America's Little Aerial Queen", to "The 5 Alferettas, Wonders of The Air" of the 1930s, there has been a long succession of Alferetta acts.)

Miss Alferetta, whose aerial exploits were probably not of the highest technical level, was interested in the young applicant (there were probably not many of them), even though Vander was a boy and his training was mostly tightwireSee Tight Wire., not trapeze or Roman ringsA pair of small wooden or metallic rings hanging from ropes or straps, used by circus aerialists as well as competition gymnasts.. Yet, he was strong, young, physically fit and, although he had developed a good musculature, it was not over-apparent. Miss Alferetta didn't want her act to be performed by a man and a woman: hers was an all-female act, and an all-female act, as she knew by experience, sold much better. She told Vander that he would need to perform in drag.Performing in drag was not uncommon in the circus; It often happened that large family troupes with too many boys had some of them performing in drag to bring diversity and a note of feminine charm to their act. Furthermore, strong female performers who could do the work of a male performer were much admired, and therefore much in demand—which led a few male performers who could get away with it to perform in drag; some of them, such as Ella Zoraya (Omar Kingsley, 1840-1879), even became true international circus stars.

To Vander, this first offer to perform, in drag or not, was the opportunity of a lifetime! Thus, dressed as a girl, Vander debuted in the circus as one of the Alferetta Sisters—whose career after this point is unfortunately not more documented than before. In any event, he was obviously credible as a "female performer."

He eventually left the sister act, and his next engagement was with Erfords' Whirling Sensation—"Climax of Aerial Art", said their advertising—a vaudeville novelty act. There are two known versions of the Whirling Sensation: The first included one man and two girls, respectively dressed as the devil and two angels (replete with wings), and the second, which came later, was made of three girls dressed as butterflies. They worked on a rotating apparatus and performed an "iron jawAerial trick in which a performer hangs from a small apparatus fitting in his/her mouth (a ''mouthpiece'' — French: ''mâchoire'') and hooked to another apparatus or piece of equipment." (hanging by their teeth) for their final trickAny specific exercise in a circus act.. Vander was likely in the second version, although he didn't give much detail in his New Yorker interview.

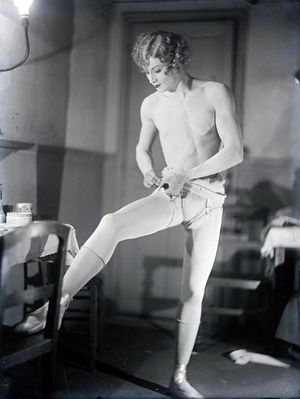

During all that time, Vander had become a proficient aerialistAny acrobat working above the ring on an aerial equipment such as trapeze, Roman Rings, Spanish web, etc., in addition to his original skills as a tightwireSee Tight Wire. artist. He had also become a good female impersonator: He had the right physical appearance, and he was naturally elegant—something his artistically-minded mother may have instilled in him at an early age. He finally decided to create his own novelty act, in which he would combine his wire walking and his trapeze and Roman ringsA pair of small wooden or metallic rings hanging from ropes or straps, used by circus aerialists as well as competition gymnasts. skills. He would perform it in drag, but, at the end, he would remove his wig and reveal his masculinity. It was an original approach, perfect for the vaudeville stage.

Enter Barbette

Female (and male) impersonators were popular in vaudeville; some of them became major stars, such as Vesta Tilley (1864-1952), Bert Savoy (1876-1923), and Julian Eltinge (1881-1941)—who had a theater named after him on Broadway, on 42nd Street (where the AMC movie multiplex stands today). However, styles differed: Whereas Savoy played it camp, Julian Eltinge tried to be as feminine, graceful, and elegant as possible; he was certainly a source of inspiration for Vander, who couldn't have ignored such a celebrated and beloved headliner.

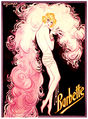

Like Eltinge, Vander wanted his appearance to be elegant, beautiful, and fully credible, and he knew how to deliver. He was also, in his acrobatic and aerial specialties, an accomplished performer. Yet, what was different from the other impersonators was the androgyny of his performance, the fact that he destroyed the illusion of femineity at the end of his act—unlike Omar Kingsley, for example, who remained Ella Zoraya at all times when in the public eye. It is this avowed androgyny that would eventually make his extraordinary success in Europe.He chose to call himself Barbette because, he said, it sounded "French and exotic." However, a barbette, in French as in English, is a "mound of earth or a protected platform from which guns fire over a parapet," which is certainly not the image he wanted to project! The correct French name to use would have been "Babette," the diminutive of Elisabeth… Be that as it may, Vander Clyde Broadway became Barbette, and it is under that name that he became part of show-business lore and legend.

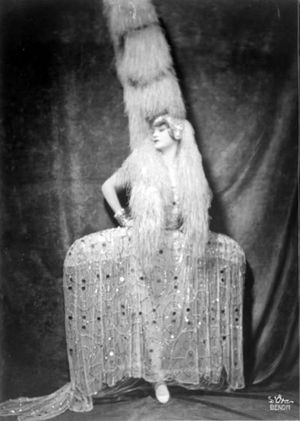

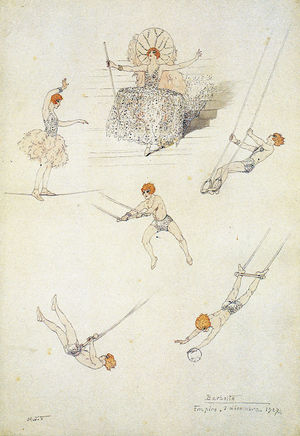

His act opened on a grand entry for which he was dressed in an elaborate and spectacular gown and headdress (which would be eventually made of ostrich feathers); then he presented a short, elegant tightwireSee Tight Wire. act and, after revealing a sparkling and scanty costume, he followed with a combination of swinging Roman ringsA pair of small wooden or metallic rings hanging from ropes or straps, used by circus aerialists as well as competition gymnasts. and low trapeze, the latter ending with a hip balance in full swing with a drop to a single knee catch, which was quite an impressive trickAny specific exercise in a circus act. at the time. For his final bow, he took off his wig and revealed his being a man, a surprise that caused a gasp in the audience. (The fact that Barbette appeared a little flat-chested was not a major problem then since flappers had made it a fashion statement to squash their breasts!)

Barbette debuted in 1919 at the Harlem Opera House on 125th Street in New York, which was part of the Keith-Albee vaudeville circuit (whose flagship was the legendary Palace Theatre, the "mecca of vaudeville," on Times Square). Without ever reaching headliner status, Barbette was successful enough to tour the Orpheum Circuit (controlled by the all-powerful Edward Albee) and to land, in January 1923, at the Palace in New York—the ultimate goal of all Vaudevillians. Then, the William Morris Agency gave him a contract for the Alhambra Music-Hall in Paris.

Located rue de Malte, near the Place de la République and the Cirque d'Hiver, the now defunct Alhambra Music-Hall had been created by the British impresario Tom Barrasford, who ran a major circuit of music halls in Great Britain. Upon his death in 1910, his circuit, including Paris's Alhambra, had passed into the hands of Sir Alfred Butt (1878-1962), Britain's most powerful impresario and theater owner, whose organization worked in association with the Orpheum Circuit in the United States. The Alhambra was one of Paris's leading variety theaters—called music-halls in French.

A Star Is Born

Between the two World Wars, Paris was Europe's circus and variety capital (closely followed by Berlin); In 1924, it had three active circus buildings, Medrano, the Cirque de Paris, and although the venerable and, sadly, poorly managed Nouveau Cirque was closing its doors, the even more venerable Cirque d'Hiver (the world's oldest circus building) was re-emerging after a short stint as a theater. Also opening its doors was the brand new Empire Music-Hall Cirque, a mixture of circus and variety theater built on the model of Berlin's famous WinterGarten varieté(German, from the French: ''variété'') A German variety show whose acts are mostly circus acts, performed in a cabaret atmosphere. Very popular in Germany before WWII, Varieté shows have experienced a renaissance since the 1980s. house. To these should be added a host of music-halls, large and small.

European and especially Parisian audiences were much more appreciative of variety and circus arts than their American counterparts; in Europe, acrobats, aerialists, equestrians, jugglers, and clowns were called artists, not just performers. Barbette had a very good act, technically as well as artistically, and his presentation was unique. He obtained an enormous success at the Alhambra and was singled out by audiences and critics alike. The great French producer Jacques-Charles took notice, and Barbette was immediately signed to participate in his new revue at the Casino de Paris, starring Mistinguett, France's greatest "meneuse de revue" (the leading star in a Parisian revue). This is where Jean Cocteau discovered him.Circus and variety shows were regularly attended by the Tout-Paris of the arts—often led by Jean Cocteau, who was the most famous influencer of the time. Cocteau's eclectic circle of friends included practically anyone that had a name in the arts, from Serge Diaghilev and Mistinguett to Pablo Picasso and Man Ray, Luis Buñuel and Guillaume Apollinaire to Sacha Guitry and Igor Stravinsky, as well as rich art benefactors such as Charles and Marie-Laure de Noailles. His influence was indeed far-reaching.

Barbette was already the talk of the town when Cocteau and his friends saw him, but his androgyny was also right up Cocteau's alley—as it was, as a matter of fact, to avant-gardists' in Paris and, even more markedly, in pre-Nazi Berlin. Cocteau, who was a sensitive and passionate man, fell in love with the artist as well as the man. (Although it is widely known that he was homosexual, Cocteau had affairs with women in his youth; however, his attraction(Russian) A circus act that can occupy up to the entire second half of a circus performance. to men and women was often more intellectual than physical.) Jean Cocteau took Barbette under his wing, introduced him to his brilliant entourage, and made him a star.

In November 1923, after the Casino, Barbette went to perform in Brussels. Cocteau wrote his friend, the music critic Paul Collaer: "Next week in Brussels, you’ll see a music-hall act called 'Barbette' that has been keeping me enthralled for a fortnight. The young American who does this wire and trapeze act is a great actor, an angel, and he has become the friend of all of us. Go and see him, be nice to him, as he deserves, and tell everybody that he is no mere acrobat in women’s clothes, nor just a graceful daredevil, but one of the most beautiful things in the theatre. Stravinsky, Auric, poets, painters, and I myself have seen no comparable display of artistry on the stage since Nijinsky."

Barbette continued to work in Europe during most of 1924. Of course, word of his huge European success reached the United States, and he was hired to appear in September 1924 at New York's Winter Garden Theater, on Broadway, in the final edition of the Schuberts' revue, The Passing Show, a second-rate challenger to the Ziegfeld Follies which desperately needed a boost. (A young dancer, Lucile LeSueur, who would later be known as Joan Crawford, was in the chorus.) Despite its newfound fame, Barbette's act was not enough to save the Schuberts' sinking ship. He returned to Paris to star in the new Empire Music-Hall Cirque, Avenue de Wagram.

The Making of a Legend

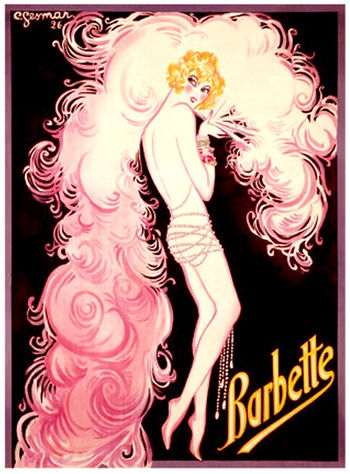

In just a couple of years, Barbette had become one of the most celebrated variety stars in Europe. Cocteau had introduced him to his friends, and made his artistic education, which was easy: Barbette had already a strong artistic instinct inherited from his mother and was intelligent. He also had a quick temper, and he began to behave like the star he was. He traveled in style with a mountain of trunks and his personal maid and had the reputation of being a martinet with his co-workers; extremely exigent when the presentation of his act was concerned, he only allowed two persons in the wings, his maid and the stage manager, and he paid great attention to every detail—which is in fact a great quality for a performing artist, and was in large part what made his such a brilliant act.Cocteau ensured that Barbette got all the help he needed: He asked Charles Gesmar (1900-1928), a prolific young poster artist and costume designer promised to a great future (unfortunately, he died of pneumonia at age twenty-eight), to design costumes and a poster for his protégé, and Man Ray (1890-1976), the surrealist artist and photographer, to make a photographic essay of Barbette at work. Another famous photographer of the period, Madame d'Ora (Dora Kallmus, 1881-1963), who specialized in fashion and frequented the same Parisian circles, did also a wonderful series of Barbette's portraits.

In the January 1926 issue of the NRF (La Nouvelle Revue Française, France's premier literary magazine), Cocteau wrote a piece titled Le numéro Barbette, which is often seen today as Cocteu's manifesto of his concept of "poetic illusion": "For, don't forget, we are in this magical light of the theater, in this box of tricks where truth no longer has any currency, where the natural no longer has any value, where short people grow taller, very tall people shrink, where card and conjuring tricks, the difficulty of which the audience has no idea, alone succeed in enduring. Here, Barbette will be the woman as Guitry was 'the Russian general'." The full text of Le numéro Barbette will be re-published in 1980, along with Man Ray's photographic essay and illustrations by Serge (Maurice Féaudierre, 1901-1992), in a book also called Le numéro Barbette.

In 1930, Barbette appeared briefly in Cocteau's avant-garde film Le Sang d'un Poète ("The Blood of a Poet"), in which many characters, some of them not even actors (like Charles and Marie-Laure de Noailles, who financed the film), were played by Cocteau's friends. It was however just a furtive moment, in which Vander, as Barbette, wearing a Chanel outfit, sat in a theater box with other characters watching a card game played on a table set up over the body of a dead boy…

Of course, one might presume that Cocteau was biased when he waxed rhapsodic about Barbette, and that his interest was not purely artistic. However, Cocteau's interest in people he supported was always primarily based on their actual talent—and he was quite discerning in that matter. He considered that Barbette's act was "an extraordinary lesson in theatrical craft." In any event, other writers' reflections on Barbette's performance unquestionably confirm Cocteau's judgment.In his book Le Cirque et le Music-Hall (1931), the journalist, novelist and screenwriter Pierre Bost said that varieties "reached a peak with an act that has often been regarded as the greatest achievement in [the genre], which has been sometimes described with rather excessive lyricism, but which is in effect an admirable accomplishment in style, technique and elegance. I am speaking of Barbette's act." He added: "His intelligence is one of Barbette's great virtues, and one cannot but admire the finesse with which he has been able to understand his act." In that, Bost was indeed describing the work of a true artist.

More significant are Henry Thétard's remarks in his seminal book La Merveilleuse Histoire du Cirque (1947), and Antony Hippisley Coxe's in A Seat at the Circus (1951). Thétard was a journalist and France's foremost circus historian and chronicler, and his opinion was that of a respected critic of the circus arts. Hippisley Coxe was a British journalist and writer, and a great circus aficionado and collector who had worked for the Bertram Mills Circus's press department and was extremely knowledgeable: He had been an amateur acrobat and—like Thétard—an amateur cat trainer(English/American) An trainer or presenter of wild cats such as tigers, lions, leopards, etc.. In his book, Hippisley Coxe said that "Barbette worked a technically excellent act."

Thétard was more voluble: "The dazzling tightwireSee Tight Wire. and trapeze act of Barbette (…) had the double characteristic of being equally interesting for the high quality of its feminine impersonation as it was for its genuine acrobatic value. However, with Barbette, the protean man took precedence, and his work was mostly remarkable for its "finish" and its perfection and elegance, more than for the difficulty of the tricks he performed. Of this Barbette was well aware, and he somewhat suffered from it for he practiced the cult of his art. He claimed, no doubt truthfully, that he could do tricks that were more difficult, but didn't want to do them for fear of giving his muscles a form that would betray his sex. (…) Yet for the public at large, easily seduced by the originality of a presentation, it is possible that the memory of Barbette, the graceful transvestite trapezist, will endure, whereas that of the splendid Alfredo Codona, who performed with the greatest of ease all the most daring tricks, will be forgotten." As far as the "public at large" is concerned, Thétard's prevision was indeed correct.

A Brilliant International Career

Although the hype created by Cocteau and his friends may give the impression that Barbette's extraordinary success was just the fad of a moment, nothing is more deceptive. Barbette's career as a circus and variety star lasted about fifteen years, which is a good run for an act of this type. (Alfredo Codona's run as a flying trapezeAerial act in which an acrobat is propelled from a trapeze to a catcher, or to another trapeze. (See also: Short-distance Flying Trapeze) star lasted only thirteen years.)

After having been an anonymous circus aerialistAny acrobat working above the ring on an aerial equipment such as trapeze, Roman Rings, Spanish web, etc. in the United States, Barbette had made a name for himself in vaudeville. As it was, his tightwireSee Tight Wire. and trapeze act was ill-fitted for the American traveling three-ring circus, which was hardly a place where one could display much refinement, and where androgynous performances were not considered suitable for what was then America's most popular form of wholesome family entertainment. (However, the illusion of femineity remained acceptable so long as the truth was not revealed to the audience!)The situation was different in Europe, where the one-ring format and, more importantly, the comfort and equipment of circus buildings, made it possible to present in the right conditions complex and sophisticated acts such as Barbette's. Over the years, he performed not only on stage, but also in the rings of Bertram Mills Circus at Olympia in London, where he was featured in the winters of 1926/1927 and 1927/1928, and at Manchester City Hall in the winter of 1929/1930; Circo Price in Madrid; Cirkus Schumann in Copenhagen; Cirque Royal in Brussels; and of the Cirque Medrano in Paris (in 1930).

Nonetheless, most Barbette's contracts were indeed for the variety stage, which was a better setting for his unique act. In France, where he was a star of first magnitude, he appeared four times at the Empire Music-Hall Cirque (the last time in 1930), as well as at the Moulin Rouge Music-Hall (which mustn't be confused with the Bal du Moulin Rouge, whose entrance was next door, and is the cabaret we know today; the former music-hall is now a nightclub), and of course, at the Casino de Paris and the Alhambra.

In the winter of 1928-1929, Barbette sailed to Australasia (it was summer there), and toured Australia and New Zealand, where his act was a great success; as it was the case everywhere, the press singled out his "clever" ending—without revealing what it was, of course. He then returned to Europe where, in December 1931, he suffered a very bad fall at the Moulin Rouge Music-Hall, thankfully without serious consequences, but it made the Parisian newspapers' front page and his engagement had to be cancelled—to the consternation of his admirers.

Barbette was also a huge variety star in Germany, where he was notably featured at Berlin's legendary WinterGarten—the last time in 1931. The following year, in March, he was at the London Palladium when he was caught backstage in a compromising position with a stagehand; homosexuality was then a crime punishable by law in Britain, and Barbette's contract was immediately cancelled and he was asked to leave the country—never to return! This may explain why Cyril Mills, in his memoirs (Bertram Mills Circus: Its Story, 1967), chose not to mention Barbette, even though he had performed three times for his father's prestigious circus.

Back To The United-States

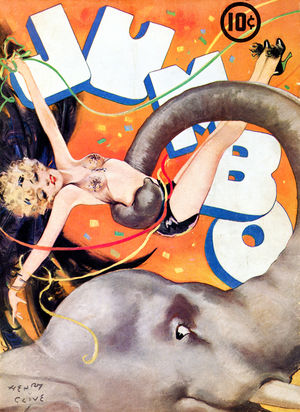

Yet, after Adolph Hitler and the Nazi party had taken power in Germany in 1933, the situation in Europe became increasingly uncomfortable for Barbette; to begin with, his perceptible homosexuality soon shut him the doors of the lucrative German variety market. Then, the prospect of war growingly became an object of concern in France, his country of choice. So, in 1935, he signed a contract with the flamboyant New York songwriter and showman Billy Rose (1899-1966), who was producing an extravagant musical, Jumbo, starring Jimmy Durante and featuring songs by Richard Rodgers and Lorenz Hart, on the stage of the mighty New York Hippodrome on Sixth Avenue.Staged by John Murray Anderson, Jumbo (which became a film directed by Charles Walters in 1962, but with a slightly different plot) featured several circus acts, including Barbette and the equestrian troupe of Poodles Hanneford. Poodles Hanneford was a bigger name in the United States than Barbette, and he was the only circus artist to get a biographical notice in the souvenir program. Barbette was featured in a tableau titled Women, along with Jimmy Durante and an aerial ballet, for which he may have lent a hand to Anderson. (Barbette would later stage the aerial ensembles for the film.) Barbette and Henderson went along famously; being a perfectionist himself, Henderson admired Barbette's thoroughness and strong work ethic. They would work together again.

Billy Rose's Jumbo opened on November 16, 1935, and closed on April 18, 1936, after 233 performances. It was not a resounding success—and neither was the film, twenty six years later. Sadly, Jumbo was the last show produced at the Hippodrome: The enormous 5000-seat theater, which had staged several circus spectaculars over its thirty years of existence, was demolished three years later, in 1939. (It had opened its doors in 1905.) Yet, Billy Rose's Jumbo left us a precious legacy in the form of a 1935 newsreel promoting the show, which includes a unique (and very short) clip of Barbette's act in rehearsal—the only one known so far.

After Jumbo, Barbette resumed his vaudeville career in the Americas. Yet, in the United States, vaudeville was on a steep decline, suffering from the double competition of the talkies (since Al Jolson had defected to sing on the silver screen in 1927) and the radio (which now harbored vaudeville's greatest comedians and singers). When in 1932, the Palace, vaudeville's most illustrious theater, converted to movies, everybody conceded that vaudeville was on its deathbed. It survived a few years, however, mostly in large theaters that offered a combination of movies and vaudeville presentations, such as the huge Loew's State Theatre on Broadway, which maintained vaudeville acts until 1947.

A Second Career

It is on the stage of Loew's State that, in 1938, Barbette's performing career ended. He said that after a performance, he sweated heavily and, since the backstage area of the Loew's State was drafty, he caught a chill. The next morning, he couldn't get out of bed: He couldn't move. He had caught a pneumonia and, even though he never gave any detail on his condition then, one may surmise that he had also contracted poliomyelitis.

What we know is that Barbette spent eighteen months at the Post-Graduate Hospital in Lower Manhattan (which has become today Tisch Hospital, part of New York University's Langone Medical Center) experimenting new treatments, going through several operations, and reeducating himself to walk. This he was able to do thanks to the amazing physical discipline he had developed throughout years of training and performing at the highest level, and of course, his athleticism. Indeed, when he put his mind to it, Barbette never did anything half-heartedly.In 1940, he returned to convalesce in his family in Round Rock. He eventually recovered his ability to walk, but his gait remained a little shaky for the rest of his life. Two years later, in 1942, John Murray Anderson was hired by John Ringling North to direct Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus's new production. John Ringling North was in the process of modernizing his uncles' old circus. Murray Anderson was there to revamp the show, which included an aerial ballet. Anderson in turn asked the only person whom he thought could improve the circus's aerial ensembles, his old friend Barbette.

Thus, still billed as Barbette, Vander entered a new career. He became, in his own words, "a trainer, trying to give young present-day acrobats some faint idea of what a refined act can be." His sense of artistic perfection was frequently offended by what he saw in the American circuses where he worked: "I know I’ll be lucky if, in return for my very handsome salary, I succeed in persuading a few young trapezists just not to chew gum during their act. Imagine!" Barbette's reputation as a martinet certainly swelled in his new line of work, but his attitude was amply justified… (Incidentally, the best illustration of the gum issue is delightfully shown by Dorothy Lamour in Cecil B. de Mille's film The Greatest Show on Earth.)

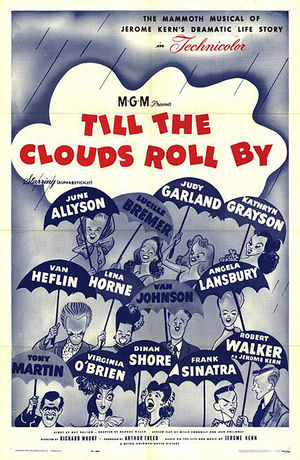

Vander continued to work for the Ringling show until the 1944 season. That year, Robert Ringling had taken over the show after the quarrelsome Ringling family's shareholders had removed John Ringling North from the presidency of the company. John Ringling North was a brilliant and creative producer, something that Robert Ringling, an opera singer who didn't have any circus experience, was not. Vander, who went along well with John North, didn't reappear in 1945. Only when North finally took full control of the Ringling organization in 1947 did Vander resume his functions as Aerial Director, along with director John Murray Anderson. He was replaced two years later by Antoinette Concello—the wife of General Manager Art Concello.However, his first assignment with Ringling put Vander (now known as Vander Barbette) back into the limelight, not as a performer, this time, but as a specialty choreographer. When Vincente Minnelli staged the circus sequence for his wife, Judy Garland, in the all-star M-G-M musical Till The Clouds Roll By (1946), a biopic of composer Jerome Kern, he hired Vander as consultant. The movie had faced major problems from the start: Kern died one month into production, and directors—among whom Busby Berkeley, who is credited as choreographer but did very little—came and went. Vincente Minnelli eventually staged himself all the sequences in which his wife appeared and received due credit for his participation. (The film overall direction was credited to Richard Whorf, who was the last director on the job). Till The Clouds Roll By was a success, and the spectacular circus scene is certainly the most lavish and most memorable of all the film's musical sequences. (Vander was not credited—a common occurrence during the studio era.)

Then, Vander was hired to choreograph circus acts for Orson Welles's huge Broadway production, Around the World, adapted from Jules Verne's novel Around the World in Eighty Days, with a book by Welles and music and lyrics by Cole Porter, and directed by Welles. It is probable that Porter, who lived in Paris when Barbette was performing there and moved in the same circles, suggested Vander to Welles. In April 1946, already saddled with financial problems, the show previewed in Boston, New Heaven and Philadelphia, where it underwent many alterations. It finally opened in New York on May 31 at the Adelphi Theatre on West 54th Street (where the Hilton Hotel stands today).

The production included an elaborate circus sequence, for which Vander had trained the performers and staged an oriental number that was one of the very few things critics liked in the show. Doomed from the start, Around the World closed on August 3, 1946, after seventy-five performances and is mainly remembered as one of Broadway's most expensive flops! (Welles claimed to have lost more than $300,000 of his own money in the venture.)

The Final Years

In the 1950s and 1960s, Vander went to work for Irving Polack's and Louis Stern's Polack Bros. Circus, which presented one-ring high quality shows sponsored by the Shriners in sport arenas. It was considered by many to be the best circus in the United States and was certainly one of the most popular. Vander was a perfect match for them; he started directing aerial ballets, and soon became the director of their productions. Among the many production numbers he created for Polack Bros. was Beauty on the Wing, an aerial ballet for which the aerialists were hanging by their teeth, donning butterfly wings—shades of Erfords' Whirling Sensation…He worked also for the Clyde Beatty Circus, which, apart from his star-director, was not in the same league. There, he was caught one day feeding a bonfire with the Circus's old, second-string aerial costumes; alerted, Beatty complained to Barbette, "Barbette, you are burning all my rainy days costumes!"—to which Vander answered: "Mr. Beatty, it never rains that hard!" At no time in his first or second careers did Barbette give in to mediocrity. Then, from 1969 to 1972, he choreographed aerial productions for Disney's touring show Disney on Parade, the forerunner of the present Disney on Ice arena shows.

Vander made other forays in film: He often consulted on circus-themed movies, most notably the film version of Jumbo (1962). However, his most enduring success in that medium is the work he did for Billy Wilder's comedy Some Like It Hot (1959), for which he trained Tony Curtis and Jack Lemmon in the subtle art of female impersonation. Billy Wilder had seen Barbette in his heydays in Berlin, and believed he was the best person for the job—although he cautioned Vander not to make his stars look too perfect!

Vander thought Curtis had good potential, but he had trouble with Lemmon, whom he considered hopeless. On his end, Jack Lemmon complained that Vander took his task much too seriously. Be that as it may, the film was an enormous hit and has since become a classic—and Lemmon won an Oscar for a part that owed a good deal to Barbette's coaching.

Disney on Parade, however, was Vander's last job. It seems that polio eventually caught up with him, in the form of post-polio syndrome, a cluster of potentially disabling symptoms that appear decades after the initial illness. He was living then with his half-sister Mary in Austin, Texas; one day, as he was hanging curtains for her, he fell and couldn't get back on his feet. Despite his immense will and strength, he could no longer move properly and became a crippled man. This he couldn't accept: On August 5, 1973, he committed suicide by overdose.

Vander was cremated, and his remains were buried in Round Rock Cemetery, where a simple stone marker indicates "Barbette – Dec. 19. 1898 - Aug. 5. 1973", with no other mention. It is fitting, however, since Vander Clyde Broadway, the kid from Round Rock, Texas, had re-created himself from scratch to become the incomparable Barbette, the world's most glamorous and celebrated variety artist.

Suggested Reading

- Jean Cocteau, Man Ray, Le numéro Barbette (Paris, Jacques Damasse, 1980) — ISBN 978-9-80003116-2

- Kyle Taylor, Wildflower — The Dramatic Life of Round Rock's First and Greatest Drag Queen – Biographical Novel (Monee, Illinois, Published by the author, 2019) — ISBN 978-1-49483959-8

See Also

- Video: Rehearsals of Jumbo featuring Barbette (1935)

- Video: Till The Clouds Roll By, Circus Sequence (1946)