Alfred Court

From Circopedia

Acrobat, Circus Owner, Animal Trainer

By Dominique Jando

Alfred Court (1883-1977) is perhaps the most remarkable French circus personality of the first half of the twentieth century. Beginning his career as an outstanding acrobat, he became a successful, yet adventurous, circus entrepreneur, first in Mexico and later in Europe, before ending as one of the greatest wild animal trainers of all times—and as such, a major circus star in Europe and America.

He was born into a wealthy family in Marseille, France, on January 1, 1883. His father, Joseph Court-Payen, worked for the family’s soap business (Marseille was then the capital of France’s soap industry), and his mother was the daughter of the Marquis de Clapier, a rich aristocrat well introduced in political circles. Alfred was the youngest of a family of ten children.

Considering his pedigree, chances that Alfred Court would become a circus acrobat were slim at best. A strong-willed kid, young Alfred was by no means rebellious, and by his own account, he had a happy childhood. But he was the last-born of a large brood, and was not necessarily expected to join in the family business. This gave him some freedom of mind. Furthermore, his parents never discouraged his early passion for circus and acrobatics—a passion he shared with his older brother, Jules (1880-1955).

Circa 1890, Alfred and Jules Court were sent to a Jesuit school in the Prado, a seaside borough of Marseille. Alfred and Jules also started training in gymnastics, which was all the rage among young men at the time: Society amateur circuses were flourishing then—like the famous Cirque Molier in Paris—and these were also the times when another sports enthusiast, the Baron Pierre de Coubertin, revived the Olympic Games (in 1896).

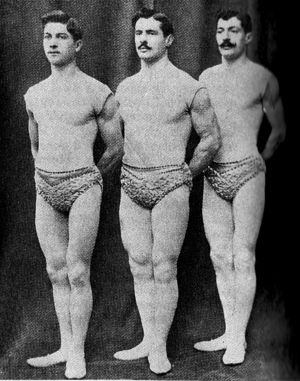

Over the years, Court developed an amazing strength, concealed by his slender build, and an outstanding talent on horizontal bars. An arduous gymnastics specialty, horizontal bars are also one of the most difficult acrobatic acts in the circus repertoire, and is rarely seen today. Yet it was relatively popular and quite alluring in the 1890s, and this was the specialty young Alfred chose to embrace for his upcoming circus debut.

Alfred Egelton

At age sixteen, Alfred Court partnered with an acrobat named Alfred Lexton, and embarked on a circus career that was to last a half-century. He left home with the blessing of his parents, promising his mother to write every day—which he dutifully did until her death, when he was in his forties. Under the name of Egelton (originally spelled "Egelthon"), which had a fashionable English sound, he made his professional debut on January 4, 1899 (according to his memoirs) at the Palais de la Jetée, a vaudeville house on a peer on the Promenade des Anglais, in Nice.The act of Lexton & Egelton was performed on three parallel horizontal bars, as was generally the custom. Alfred "Egelton" Court was a perfectionist and trained indefatigably, a quality that, to Court's dismay, his partner didn’t share; in spite of his young age, Court was already a remarkable barriste (the French word for horizontal bar acrobats), able to perform practically all the most difficult tricks in the repertoire.

After their stint at the Palais de la Jetée, Lexton & Egelton were offered an engagement with the Cristiani circus, of the famous Italian equestrian family, which had just returned from Spain, and was traveling through France on its way back to Italy. Thus Alfred Court made his circus debut in Bayonne (in the southwest of France) with Circo Cristiani in 1899.

The act of Lexton & Egelton was enjoying a successful run, until Alfred Court had a bad fall, serious enough to incapacitate him for several weeks. Alfred Lexton couldn’t stay without work for that long and he took advantage of an offer to work in Germany. Court and Lexton parted ways amicably, and the Lexton and Egelton act ceased to exist. Without a partner, Alfred Court worked for a few months with a small traveling theater company, and then returned to Marseille.

Back home, Alfred Court teamed up with his brother Jules and a remarkable lightweight acrobat, "Féfé" Gavazza. The new "Egeltons" went on to perform successfully all over Europe and finally with the popular circus Pinder, with which they toured the French provinces from 1905 to1908. At circus Pinder, Alfred met his future wife, the talented equestrienneA female equestrian, or horse trainer, horse presenter, or acrobat on horseback. Renée Vasserot.

Circus Producer

At the same time, between engagements, the Court brothers tried their hand at producing, and presented their own Cirque Egelton shows in temporary wooden circus structures (known as constructions) erected in French provincial towns during seasonal fairs. They also developed a "Looping the Loop" thrill actA spectacular act that focuses on the display of danger, whether real or staged. on a bicycle (a popular type of attraction(Russian) A circus act that can occupy up to the entire second half of a circus performance. at the time), which they quickly abandoned: Like all attractions of that genre, it was impeded by cumbersome equipment that was difficult to transport, let alone to install in the ring.

Jules Court left the Egeltons’ bar act at the end of the 1908 season, and went on to create a talent agency. The brothers, however, had decided they would have their own traveling circus as soon as they had gathered a sufficient capital. Meanwhile, in 1909, their home city of Marseille gave them the authorization to build a wooden circus construction(French) A temporary circus building, originally made of wood and canvas, and later, of steel elements supporting a canvas top and wooden wall. Also known as a "semi-construction." on the Place Saint-Michel.The new Cirque Egelton was a comfortable and elaborate structure that could accommodate 3,800 spectators—a number probably inflated by their publicity. Until 1913, it offered remarkable circus programs that met with great success. But these programs, which changed regularly, were more expensive than Alfred and Jules Court could truly afford, and the brothers had to declare bankruptcy in 1912. They reorganized as Cirque Standard for the 1913 season, their last in that building.

In the winter of 1912, the Court brothers had also toured in association with the famous Italian daredevil and circus entrepreneur, Ugo Ancillotti (1869-1925), with a traveling circus under a big topThe circus tent. America: The main tent of a traveling circus, where the show is performed, as opposed to the other tops. (French, Russian: Chapiteau), the Cirque Impérial Russe. It was a short-lived venture—not too surprisingly since the Russian flavor of the program had been created by giving pseudo-Russian names to the performers; Renée Vasserot, for example, was billed as "Madame Vasseroff."

Alfred Court had developed a taste for circus under canvas at Cirque Pinder, and owning his own traveling big topThe circus tent. America: The main tent of a traveling circus, where the show is performed, as opposed to the other tops. (French, Russian: Chapiteau) was what he truly wanted. He began to make plans for the creation of a Zoo Zirkus (with this German spelling), but everything came to naught when the Great War started in August 1914 after the assassination in Sarajevo of the Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria. By then, however, Alfred Court had already left Europe, and was performing in the United States with the Ringling Bros. Circus.

The Orpingtons And Circo Europeo

After his brother had called it quits, Alfred Court had created a new hand-to-handAn acrobatic act in which one or more acrobats do hand-balancing in the hands of an under-stander. acrobatic act, The Orpingtons, with his wife, Renée, and a student of his, Louis Vernet. It was again a remarkable act, showcasing Alfred Court’s remarkable strength. It had eventually caught the attention of Charles Ringling and, in May 1914, The Orpingtons debuted with the Ringling Bros. Circus in Chicago.The Orpingtons had a two-year contract with Ringling. For the 1915 season, they added a perch-poleLong perch held vertically on a performer's shoulder or forehead, on the top of which an acrobat executes various balancing figures. act to their repertoire, which they performed in the center ring. During the winter months, they played dates in Cuba, where they eventually got a long-term engagement with Antonio Vicente Pubillones, in his popular Circo Pubillones. They performed there in 1918 with their hand-to-handAn acrobatic act in which one or more acrobats do hand-balancing in the hands of an under-stander. and perch-poleLong perch held vertically on a performer's shoulder or forehead, on the top of which an acrobat executes various balancing figures. acts, and shared the bill with Alfredo Codona, who had just left the Siegrist-Silbons troupe and was performing his own flying trapezeAerial act in which an acrobat is propelled from a trapeze to a catcher, or to another trapeze. (See also: Short-distance Flying Trapeze) act for the first time.

During this engagement, Alfred Court had an insider look at the sometimes improbable way circuses operated in Central America—and he didn’t fail to notice their attractive financial prospective. At the end of 1918, he joined forces with the Mexican Mijares family to create the Circo Europeo, a show with a 2,000-seat big topThe circus tent. America: The main tent of a traveling circus, where the show is performed, as opposed to the other tops. (French, Russian: Chapiteau) they toured by train and boat in remote Mexican areas that rarely saw circuses, with short incursions into Honduras and Guatemala.

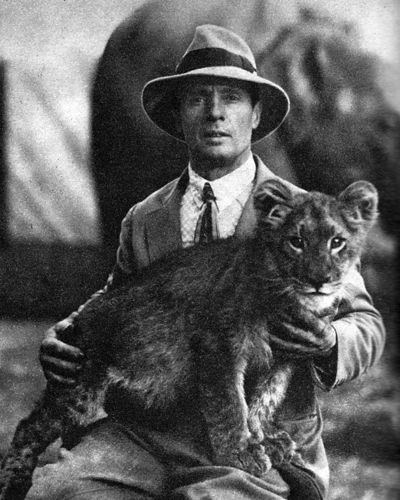

It is during this Mexican tour that Alfred Court became a wild-animal trainer: Unable to find a replacement for a drunken lion trainer he had fired, he decided to present the act himself. He had nurtured a keen interest in big cats for a while, and this experience would transform this interest into a passion that lasted a lifetime, and would practically cost him the circuses he later created in France.

Circo Europeo had secured the services of a legendary and flamboyant Mexican circus impresario, Don Juan Treviño, who was in reality a French expatriate from Bordeaux. Treviño, a street-smart entrepreneur who had created his own Circo Treviño in 1897, had fallen out of luck, and served Court as a mixture of advance man and fixer, using his vast experience in touring circuses around Mexico—as well as his considerable talents at swindling unwary locals.

When World War I came to an end with the Treaty of Versailles in June 1919, Alfred and Renée Court decided to return to France, and Court sold the equipment of Circo Europeo at a low price to his friend Don Treviño. Court’s partner, Louis Vernet, remained with Treviño in Mexico, where he created a perch-poleLong perch held vertically on a performer's shoulder or forehead, on the top of which an acrobat executes various balancing figures. act with a new partner named Evans.

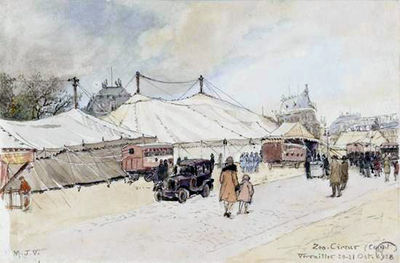

Back to Paris, and flush with American dollars, Court revived his association with the aging Ugo Ancillotti. They ran for a short while a tenting circus that opened in Versailles in 1920, and began touring the French provinces. This new association was short lived: Ancillotti was ill (he would die a few years later, in 1925), and he quickly sold his interests in the company (notably its equipment) to Alfred Court.

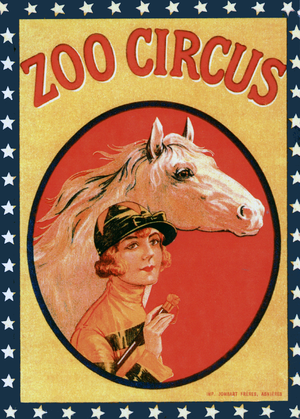

The Zoo Circus

Meanwhile, Court had resumed his acrobatic training with his wife and a new partner, Lucien Goddart. Most importantly, he had revived his work on the Zoo Zirkus project, which had been interrupted by the war. The circus title was changed to Zoo Circus, which certainly sounded better at this point to French ears, and with Ancilotti’s equipment as a foundation, it was now ready to go. Jules Court came aboard to take care of the administrative side of the project.

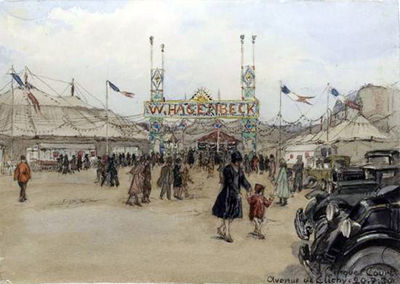

The Zoo Circus came to life in Limoges, France, in the spring of 1921. It was, in many aspects, an original concept in France: A circus with a vast menagerie (inspired at first by the German circus of Carl Hagenbeck—thus the original title, Zoo Zirkus—but also, undoubtedly, by the American circuses Court had seen in the United States). It traveled daily with the help of a fleet of motorized vehicles—at a time when French circuses customarily moved either by train, or, like Pinder, with horse-drawn carriages.The menagerie was contained in a single large tent adjacent to the big topThe circus tent. America: The main tent of a traveling circus, where the show is performed, as opposed to the other tops. (French, Russian: Chapiteau), as was the custom in the United States, and it included ethnic exhibitions, a trademark of Zirkus Hagenbeck, and sideshow attractions like those Court had seen at the Ringling Bros. Circus. The menagerie, in its first season, was still a little light and, oddly, there was no cage act(English/American) Act performed in a cage, such as lion or tiger acts. in the performance until December, when the German trainer Otto Sailer-Jackson was hired with a group of tigers from Circus Krone.

Sailer-Jackson was a celebrated cat trainer(English/American) An trainer or presenter of wild cats such as tigers, lions, leopards, etc. from the Hagenbeck school. He stayed with the Zoo Circus for the Holiday season, long enough to give Alfred Court the opportunity to observe his work attentively, which he would emulate, down to the "cowboy" costume. The Hagenbeck method consisted of using the cats’ natural abilities to create acts that emphasized the animals’ innate talents—instead of simply showing the confrontational image of "man vs. beast" favored by the so-called "lion tamers" of the nineteenth century.

The Court menagerie expanded in 1922 with the purchase of a large group of polar bears from Hagenbeck, which Alfred Court presented himself (as Egelton) the following season, in a program that also included the seven lions of Martha-la-Corse, and the group of lions and tigers presented by her husband, "Le Dompteur Marcel" (Marcel Chaffreix). Martha-la-Corse and Marcel were well known in the traveling menagerie business, and the addition of their acts and their animal collection to the Zoo Circus lineup helped at last to fully justify its name.Alfred Court eventually developed his own wild animal collection. At the end of 1924, he began advertising cage acts for rent to other circuses, including a group of ten tigers, another of eighteen lions, his own group of twelve polar bears, a group of ten panthers, and a mixed group of wolves and hyenas. The latter was one of the groups presented within the menagerie tent itself during the tour.

The immediate aftermath of World War I was a booming period for European circuses, and the Zoo Circus steadily grew in importance, becoming one of France’s premier tenting circuses. By 1925, the menagerie boosted a collection of 25 lions, 8 tigers, 9 hyenas, 7 wolves, 3 cougars, 12 polar bears, 16 panthers and leopards, 5 jaguars, 2 cheetahs, and an extensive assemblage of exotic animals, including antelopes, llamas, and camels, down to monkeys, porcupines and mongooses.

Court had now in his employ two trainers to assist him, who would in time build brilliant careers on their own: Vojtech Trubka, who presented the polar bears, and Johnny de Kok, who was in charge of a group of ten lions. In time, several others would come and work with Court. Court himself presented his tigers, and was now using his real name. Unlike his German and American models, however, the Zoo Circus never had a significant herd of elephants: The largest Court ever lined up was a group of eight pachyderms presented by his brother-in-law, Eugène Vasserot, in 1928.

The Many Circuses Of Alfred Court

The 1927 season marked the Zoo Circus’s apogee—immediately followed by the beginning of its decline. His initial success had led Alfred Court to expand beyond his means—something that had strained his relations with his brother Jules. Consequently, the brothers decided to create two separate units of the Zoo Circus, one touring in France, under Jules’s management, the other in Spain, under Alfred’s management. This move resulted in a very profitable season, both tours having been successful, with the Courts’ vast zoological collection supported by the income of two circuses instead of a single one.The following year, in association with a French circus entrepreneur, Pierre Périé, they sent a Barnum’s Circus on the road. It was a three-ring affair that professed to be the American original, but with a program that was not, by any stretch of the imagination, up to par: The enterprise didn’t last long. Meanwhile, the Zoo Circus continued its tour, with Alfred Court presenting the first of his remarkable mixed-animals cage acts, which comprised ten lions, two tigers, a cougar, seven brown and white bears, and a couple of great Danes.

At the end of 1928, the Courts set up their three-ring big topThe circus tent. America: The main tent of a traveling circus, where the show is performed, as opposed to the other tops. (French, Russian: Chapiteau), renamed Arène Olympique, in their hometown of Marseille. This time, they filled the rings with a truly strong show, which ended with three simultaneous cage acts: A group of twelve lions presented by Vargas, the mixed group, which now included twenty-three animals, presented by Max Stolle in the center ring, and Alfred Court himself with his group of eight tigers.

With close to fifty high-quality acts, the Arène Olympique show was impressive indeed, and at the beginning of its run, the audience came en masse. But the weather changed suddenly, and a surprisingly cold winter hit the habitually balmy Mediterranean city of Marseille. The tent was not heated, and the audience quickly dwindled. The show folded after one month. It was a financial disaster.

A severe cold front enveloped Europe that winter. When Alfred and Jules Court tried to resume the 1929 season under the Zoo Circus big topThe circus tent. America: The main tent of a traveling circus, where the show is performed, as opposed to the other tops. (French, Russian: Chapiteau), it collapsed under a snowstorm. Trying to raise money quickly, they revived their three-ring big topThe circus tent. America: The main tent of a traveling circus, where the show is performed, as opposed to the other tops. (French, Russian: Chapiteau) and the Barnum’s Circus deception, hoping that, with the proper advertising, the paying public would take the bait. They toured it until November, but with a program that didn’t match what the advertising promised.

Meanwhile, the Zoo Circus hit the road again under the management of Alfred's nephew, Charles Court, with a show that was again what the public had been accustomed to. However, although there were some good acts, there was no cage act(English/American) Act performed in a cage, such as lion or tiger acts., and the animal contingent was reduced to a chimpanzee act, and two equestrian displays: To raise money, Alfred Court had placed his wild animal acts with other circuses.At the end of the season, the Courts were in a bad financial shape. The postwar boon had ended, and the competition had become fierce. In 1930, the Zoo Circus went back on tour, and the Courts rented the name Wilhelm Hagenbeck from the Hagenbecks, and sent a second unit on the road with a show that, this time, was true to the Hagenbecks' name and reputation: Exotic tableaux were interspersed throughout the performance, and the second half was dedicated to three important cage acts—Willy Hagenbeck’s sixteen polar bears presented by Carl Herbig, Court’s tigers presented by Kovack, and a mixed group of ten lions, four bears, two leopards, two cougars, two hyenas, two wolves and two German mastiffs presented by Max Stolle.

The Cirque Wilhelm Hagenbeck played Paris in July with good success. At the end of the season, the Courts had managed to be in the black again. The Zoo Circus and the Cirque Wilhelm Hagenbeck went back on the road in 1931, but, this time, the business was disappointing. The Courts sent only one show on tour the following year, a tenting affair they called Robinson And His Savage Tribes. It was a mixture of Wild West exhibition and classical circus acts that were sprinkled with an exotic flavor.

Unfortunately, Robinson’s special blend of Wild West and fake exoticism failed to attract the public attention, and the Courts returned to the Zoo Circus title, thinking that it had better chances to attract audiences into the big topThe circus tent. America: The main tent of a traveling circus, where the show is performed, as opposed to the other tops. (French, Russian: Chapiteau). It was perhaps too late: Alfred Court's yearn for for new experiments, instead on focusing on the stabilization and development of his Zoo Circus, had finally caught up with him. At the end of 1932, the situation was beyond repair; Alfred and Jules Court folded their tents and filed for bankruptcy.

Alfred Court, Cat Trainer

The brothers parted ways. Jules Court became Cirque Pinder’s administrative manager, while Alfred began training cat acts that he could rent to various circuses. He had two trainers in his employ, Vojtech Trubka, who presented his group of tigers, and Violette d’Argens, with a group of lions. But his directorial ambitions had not left him, and he was ready to launch yet another circus.

In association with Pierre Perié and Jean Roche, he created the Cirque Olympia, which was to tour the south of France and then travel in Spain. It was a very modest circus that hit the road in June 1934—although its publicity inflated considerably its importance. But the Spanish audiences were not fooled, and the show eventually folded in July. In December, Court transformed what was left of his circus into a traveling menagerie, which he toured for one season, in 1935. His days as a circus owner were over.Alfred Court started again working as a performer. He presented La Paix dans la Jungle ("Peace in the Jungle")—a group of three lions, two tigers, two leopards, three polar bears, and three black bears—at Paris’s Cirque Medrano in February 1936. It was the beginning of a very successful international career as a wild animal trainer. Meanwhile, his other cage acts were still engaged with various circuses all over Europe.

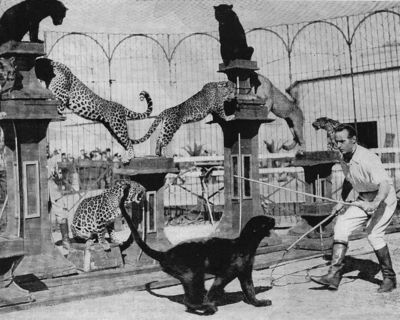

The following year (1937), Alfred Court trained a new group of fifteen small cats that comprised nine leopards (including three black specimen), a rarely seen snow leopard, four cougars and a black jaguar. He was now working in Europe’s most important circuses and variety theaters, including the legendary Wintergarten in Berlin and the Empire Music-Hall Cirque in Paris.

When World War II started in Europe in September 1939, Court was finishing the season at the Tower Circus in Blackpool, England. His three other acts were scattered in Scandinavia: two mixed groups and the tiger act. He managed to gather his troupes and bring the rest of his menagerie and his employees to England. Earlier, Court had received an offer from John Ringling North to come to the United States and work with his animals on The Greatest Show On Earth. He had refused at first, but these were different times: When North reiterated his offer, Court took it.

Circus Star in America

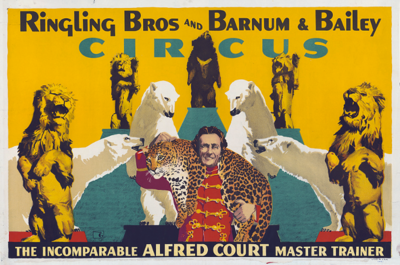

In Liverpool, Alfred Court embarked eighty animals, twenty employees, and all his equipment on the West-Chatala, which took sail for the New World. He and his wife embarked soon after on the Manhattan in Genoa, Italy, which was close to Nice, where they now lived. They arrived in Sarasota, Florida, where Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey had its winter quarters, in time for rehearsals before the season opening at Madison Square Garden, in New York, on April 4, 1940.

Court opened the program with three simultaneous cage acts—three mixed groups presented by Harry and May Kovar, Fritz Schulz, and Court himself in the center arena. Other trainers would come to assist or replace them, including Damoo Dhotre, Joseph Walsh, and Court’s nephew, Willy Storey (who would be his last apprentice) among others. Court’s contract, signed for two years, was renewed at the end of the 1941 season.But there had been changes: In August, a fire had destroyed the menagerie tent; more than sixty circus animals died. Court’s cages were usually kept behind the big topThe circus tent. America: The main tent of a traveling circus, where the show is performed, as opposed to the other tops. (French, Russian: Chapiteau) for the performance, and his animals were not injured. But the incident resulted in an internal crisis among the shareholders of the Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey corporation (all members of the Ringling family), which led John Ringling North to resign as president of the circus. His cousin, Robert Ringling, an opera singer, took the reins.

As fate would have it, Robert Ringling eventually presided over a far greater tragedy than the menagerie fire: On July 6, 1944, in Hartford, Connecticut, a fire destroyed the big topThe circus tent. America: The main tent of a traveling circus, where the show is performed, as opposed to the other tops. (French, Russian: Chapiteau) during a performance. There were 168 victims, among whom 84 children, and 487 others suffered burns or injuries. It had happened soon after Court’s three-ring display, and the steel tunnels that had linked the outside cages to the steel arenas in the rings were still in place; many deaths occurred when panicked spectators piled up against one of these tunnels, which obstructed a narrow exit.

In his memoirs, Court blamed the safety code that was then in place: the size and distribution of the exits were inadequate for the 12,000-seat tent of the giant circus. He had himself complained about the narrowness of the corridors where the tunnels leading to the side rings were set up: His helpers had barely enough room to move between the tunnels and the bleachers, and this proximity put them constantly at risk from being mauled by the cats they led back and forth in the narrow space.

But, as they say, "the show must go on," and so it went. For the 1945 season, Alfred Court had noted that Robert Ringling liked to see pretty showgirls in the ring with practically every act. He offered to create an act with twelve leopards and twelve dancers together in the cage. The number was eventually reduced to six courageous girls, and the act was presented in the center ring by Willy Storey and Damoo Dhotre. By then, Court, who was sixty-two, had completely retired from the ring.

Epilogue

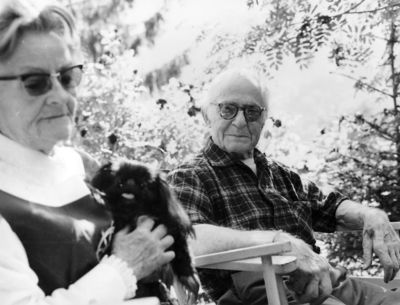

In May, the Germans surrendered, and the War in Europe was over. At the end of the season, Court disposed of some of his animals, and he returned to France at the beginning of 1946. He later sold what was left of his menagerie to the Amar brothers, including the group of small cats presented by Damoo Dhotre—who returned from the United States in 1949. Then, Renée and Alfred Court retired definitely to their villa in Nice. A prolific raconteur, Court began to write his memoirs, parts of which were published in various magazines, and much later, in 2007, edited as a book. Some of what concerns his career as an animal trainer was also published in book form in France, England, Germany and the United States. But the bulk of his writings remains unpublished.On December 30, 1974, the Jury of the first International Circus Festival of Monte Carlo, presided by Prince Rainier III of Monaco, awarded Alfred Court a Gold Clown in tribute to his exceptional career. A few days later, Prince Rainier, an amateur cat trainer(English/American) An trainer or presenter of wild cats such as tigers, lions, leopards, etc. himself, went to visit Court in his villa in Nice and presented the ninety-one-year-old cat trainer(English/American) An trainer or presenter of wild cats such as tigers, lions, leopards, etc. with the award. Alfred Court was back in the limelight for one last time, and his legend got an ultimate boost. He passed away three years later, on July 1, 1977. He was laid to rest in the Caucade cemetery in Nice, his final hometown.

Suggested Reading

- Alfred Court, La cage aux fauves (Paris, Éditions de Paris, 1953)

- Alfred Court, Wild Circus Animals (London: Burke Publishing Co., 1954)

- Alfred Court, My Life With The Big Cats (New York, Simon and Schuster, 1955)

- Alfred Court, Mein Tiger Brahma (Stuttgart, Frankhsche, 1955)

- Dominique Denis, Les Zoo Circus des frères Court – 2 vol. (Aulnay-sous-Bois, Editions Arts des 2 Mondes, 2004) – ISBN 2-915189-06-4

- Alfred Court, Mémoires d’Alfred Court (Aulnay-sous-Bois, Editions Arts des 2 Mondes, 2007) – ISBN 2-915189-11-0