Giuseppe Chiarini

From Circopedia

Contents

- 1 Equestrian, Circus Entrepreneur

- 1.1 The Chiarini Family

- 1.2 Enter Giuseppe Chiarini

- 1.3 Chiarini’s Royal Spanish Circus

- 1.4 Chiarini in Mexico

- 1.5 World Traveler

- 1.6 First Trip To Australia And The Far East

- 1.7 Back To The Americas

- 1.8 Australasian Encore

- 1.9 China And The Orient

- 1.10 Australia, China And Japan

- 1.11 The Final Years

- 2 Note On Sources

- 3 Suggested Reading

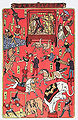

- 4 Image Gallery

Equestrian, Circus Entrepreneur

By Dominique Jando

Giuseppe Chiarini (1823-1897) was perhaps the most influential circus director of the nineteenth century: During a professional career that spanned fifty-eight years, his extensive and incessant international tours led him from Europe to North and South America, to India and Asia, and down to Australia. In many places that had not yet been exposed to the circus, Chiarini’s was the first circus the locals had ever seen—and this exposure sometimes triggered there the creation of an indigenous circus inspired by Chiarini’s shows.

Over the years, Chiarini performed for Tsar Nicholas I of Russia, Emperors Maximilian I of Mexico, Dom Pedro of Brazil, Mitsuhito of Japan, King Rama V of Siam, an assortment of Indian Rajahs, and for various government officials and politicians. His Royal Italian Circus—which could become Royal Spanish Circus when needed—was in fact an American enterprise based in California. A true circus man, Chiarini was indubitably a citizen of the world.

The Chiarini Family

Giuseppe Chiarini came from a large and ancient Italian family of traveling entertainers, whose first recorded appearance was at the Foire Saint-Laurent, one of France’s oldest fairs, in 1580. Many Chiarinis, more or less directly related to Giuseppe, have since been chronicled in popular entertainment and circus history—a very diverse crowd of acrobats, ropedancers, puppeteers, ballet dancers, and equestrians.

In his novel, Die Vagabunden (1895), the German poet Karl von Holtei immortalized one of them, Francesco Chiarini; in the 1780s, this Chiarini managed a company of acrobats and puppeteers, and ran a very successful Théâtre d’Ombres Chinoises (shadow puppet theater). His daughter, Angélique, a celebrated equestrienneA female equestrian, or horse trainer, horse presenter, or acrobat on horseback., had been featured in 1793 at the Amphithéâtre Franconi—the former Amphithéâtre Astley—in Paris, and later in the troupe of Jacques Tourniaire.

Another branch of the Chiarini family was that of the "Première Grande Troupe Mimo-Chorégraphique Chiarini (créée en 1710, aux Fuanmbules de Paris, par son Grand-père)" ("The premier great mime-choreographic Chiarini company, created by his grandfather in 1710 at Paris’s Théâtre des Funambules"), from which came the famous nineteenth-century ropedancer, Adélaïde Chiarini.

Enter Giuseppe Chiarini

Giuseppe Chiarini was born in 1823 in Rome, then the capital of the Papal States. His father, Gaetano, was a trickAny specific exercise in a circus act. rider and horse trainer who had worked for the Franconis—and Giuseppe himself would later be known as a pupil of Adolphe Franconi, which was indeed an excellent reference. In time, the young Chiarini became a remarkable horse trainer, high-schoolA display of equestrian dressage by a rider mounting a horse and leading it into classic moves and steps. (From the French: Haute école) rider, and a versatile all-around equestrian.At age sixteen, Giuseppe joined the company of another great Italian equestrian and director, Alessandro Guerra (1782-1862)—whose aggressive performing style had won him the nickname, "Il Furioso." With him, Chiarini went to perform from Vienna, where Guerra was based, to Eastern and Northern Europe, and to St. Petersburg, then the capital of Imperial Russia, where Guerra opened a resident circus in 1845. Giuseppe stayed in St. Petersburg until the end of 1846, at which time Guerra’s circus was overcome by the competition of Paul Cuzent’s Cirque de Paris (which was to become Russia’s first Imperial Circus). Guerra and most of his company, including Chiarini, returned to Vienna.

In the early 1850s, Chiarini went to work in London at Astley’s, then under the direction of William Batty. It was there that Chiarini’s career began to take a different direction: In 1852, Batty engaged into a venture with the American circus entrepreneur Seth B. Howes (1815-1901) to bring to New York what was announced to be the troupe of Paris’s famous Hippodrome, created in 1845 by Laurent Franconi and his son, Victor.

In actuality, the Parisian Hippodrome was then under the management of an impresario named Arnault: Both Laurent Franconi and his brother, Henri, had died in 1849. This touring Hippodrome, which was supposedly managed by Henri Franconi, was a creation of Batty—who had used the lesser-known of Henri Franconi’s sons, Henri Narcisse Franconi, as a front to give the enterprise a veneer of authenticity.

Nonetheless, Franconi’s Hippodrome opened in New York on May 2, 1853, on the site of Thompson Madison Cottage (which would give its name to the first Madison Square Garden). The troupe was made of some of Batty’s performers—among whom Giuseppe Chiarini, his wife, and his daughter, Josephine—and elements of the Sands, Lent and Co.’s American Circus company, which had been traveling in England the previous years.

After his participation in the Franconi venture, Giuseppe Chiarini stayed in the United States. He appeared in New York at the Bowery Amphitheater in September 1853 (while Josephine played Little Eva in Uncle Tom’s Cabin at Barnum’s Museum on Broadway), and later toured with the Van Amburgh Circus of Lewis B. Titus and John June.

He was back in New York at the Bowery Amphitheater in March 1854. At this point, Giuseppe had just started his career as a circus impresario, and had entered into a partnership with Richard Sands (1814-1861) of the Sands, Lent & Co. Circus. Chiarini and Sands’s Italian Circus toured New England, and went as far east as the Great Lakes. By 1856, Giuseppe was ready to start his very own circus.

Chiarini’s Royal Spanish Circus

Immediately targeting remote and rarely visited territories, Chiarini opened his Royal Spanish Circus in the early months of 1856 in Havana, Cuba. Cuba was still a Spanish possession then, and Royal Spanish Circus was a more appropriate title than the Royal Italian Circus Chiarini would adopt later (although his enterprise was mostly referred to as Circus or Circo Chiarini). The famous American equestrian John Glenroy (1828-1902)—who is credited with having completed the first somersault on a bareback horse—was performing in Cuba at the time, and he and his company joined Chiarini’s circus for a couple of seasons.

In 1858, Chiarini established a partnership with the British acrobat George Orrin (1815-1884), and continued touring the island of Cuba with a strong circus program that included his wife Giuseppina, his daughter Josephine, and the young British equestrienneA female equestrian, or horse trainer, horse presenter, or acrobat on horseback. Katie Holloway, whom he regarded as a daughter. In spite of an epidemic of yellow fever that hit the company, they continued in 1859 through Haiti and the Dominican Republic.

The following year, he visited Cuba again, this time in partnership with the American circus entrepreneur, James N. Nixon (1820-1899). Then, Giuseppe embarked in an extended tour of the West Indies that lasted until early 1864. During that time, he added to his troupe two young Cuban slaves, Berien and Teodora, whom he freed and trained to be an equestrienneA female equestrian, or horse trainer, horse presenter, or acrobat on horseback. and a ropedancer respectively.

These first eight years had been very profitable, especially since Chiarini had concentrated his travels to territories out of the beaten path, and not often visited by circus companies. Then, on May 8, 1864, Chiarini and his troupe set sail from Havana to Vera Cruz, where they began an extended tour of Mexico.

Chiarini in Mexico

This time, Chiarini showed his true colors, and traveled under the name of Signor Chiarini’s Royal Italian Horse Troupe—later to be known as Chiarini’s Royal Italian Circus. In 1864, his company included Josephine Chiarini, who was the "principal equestrienneA female equestrian, or horse trainer, horse presenter, or acrobat on horseback.;" Katie Holloway, billed as the "Italian Equestrienne;" Señorita Olivera, as the "Spanish Equestrienne;" and Palmyra Holloway (Katie’s sister), as the "English Equestrienne." Benoît Tourniaire completed the equestrian department, with Giuseppe himself, and his young apprentice, Berien. The bill was rounded off with the Orosco Brothers, "Spanish Gymnasts from Madrid;" Rodriguez, "Andalusian Jester;" Camillo in the "Zampilaerostation" (an aerial act); and Chiarini’s other apprentice, the young Theodora, dancing on the tightrope.

Again, Chiarini’s Mexican tour was very successful, and this led him, in 1865, to build a superb circus in Mexico City, at 5 Calla de Gante, on what had been the site of the Convent of San Francisco, leveled down by a catastrophic fire five years earlier. The Circo de Chiarini was a stone amphitheater of 3,000 seats, designed after the then prevalent European model, with a ring and a stage, and outfitted with a royal box for the new Emperor Maximilian I, who had just begun his short reign over Mexico (it lasted from 1864 to 1867).

Prior to the opening of Circo de Chiarini on Calla de Gante, Giuseppe gave a command performance at Chapultepec Castle, where the Emperor presented him with a sapphire broach surrounded with diamonds. As legend has it, the Emperor also asked him to break Abd-el-Kader, a difficult Arabian stallion he had received as a gift from his brother, the Emperor Franz-Joseph of Austria.

Two weeks later, on March 20, 1865, Chiarini opened his amphitheater in the presence of the Imperial family. For the occasion, he exhibited a perfectly tamed Abd-el-Kader; the delighted Emperor immediately presented the stallion to Chiarini (or perhaps was he simply relieved to have finally parted with the recalcitrant horse)—and the shrewd circus entrepreneur made Abd-el-Kader the equine star of his stables. "Si non è vero, è ben trovato," as Chiarini himself would have said…

Although he had now a home base, Chiarini continued his travels. He returned to Cuba at the end of 1865 with his company, and performed there again in 1866. The political climate in Mexico was deteriorating anyway, and avoiding the country was indeed a good move. The composition of Chiarini’s company changed frequently, but it regularly included some of the greatest names in the business—such as the equestrians James Robinson, Robert Stickney, James Melville, and Ella Zoyara (Omar Kingsley), and the celebrated acrobatic troupe of the Hanlon Brothers.

Afterward, Chiarini went to play in New York in June (1866), at the Hippotheatron on 14th Street, and spent the winter in New Orleans. A full-fledged revolution had erupted in Mexico, and the situation there was volatile: Mexico City would fell to the Republican forces of Benito Juárez in February 1867, and the Emperor would be dethroned in May and executed the following month. In 1868, for a short time, Chiarini’s vacant circus in Mexico City housed the new Mexican Parliament.

World Traveler

After New Orleans, Giuseppe embarked on an extended tour of the West Indies, Central America, and Panama, and from there sailed to California—which he toured in 1868. He continued his American tour in Nevada, and then returned to California and stopped in its then largest city, San Francisco, where he performed in 1869 in association with the circus of Lee & Ryland (Henry C. Lee, 1814-1885, and George F. Ryland, 1826-1890).

Then he continued his travels, playing Panama City, from where he sailed to Valparaiso, Chili. Chiarini visited Santiago, crossed the Andes to Argentina, where his company performed at the Teatro Hippódromo, Buenos Aires's circus building, under the title Circo Italiano de Chiarini—which sounded better than Royal Italian or, worse, Royal Spanish Circus in a country that had severed its colonial ties with the Spain and had been in constant revolution for several years.

It was not the first visit of a Chiarini to Buenos Aires: In 1829-1830, another Giuseppe Chiarini (related to our Giuseppe) came to present Arlequinades, rope dancing and "voltige à la Française" (tumbling) with his wife Angelita, his daughter Maria and a young apprentice called Blas Noi. They were probably the Chiarinis who appeared in Paris's Théâtre des Funambules in the troupe of the famous mime, Deburau—some among the many Chiarinis who performed in Europe.

After Argentina, Giuseppe's circus reached Brazil, where it played in Bahia, Rio de Janeiro, and toured Pernambuco. Late in the summer of 1869, Chiarini finally returned to Mexico City, where he found himself in serious competition with the French acrobatic troupe of the Buislay family. (Later that year, the Buislays, in association with Ricardo Bell, rented the Circo de Chiarini building, where they presented a series of successful shows.)

At the end of the year, Chiarini returned to California. By then, San Francisco had become his home base. (His descendants would eventually settle in the San Francisco Bay Area, notably in Oakland.) After a run in the great Californian city, Chiarini’s troupe traversed the continent and set sail across the Atlantic: Giuseppe returned to the Old Continent for the first time in seventeen years, and landed in Portugal.

He had taken with him the main elements of his company (including Katie Holloway, Berien, and Teodora), and thirty horses and ponies. A number of performers crossed with him (among which a few English, American, and South American artists), but it seems that part of the cast was hired locally. The Royal Italian Circus performed in Lisbon, then moved to Spain, where it appeared in Madrid and probably a few other cities. This would be Chiarini’s last trip to Europe.

From there, the troupe returned to the Americas, and was again in Buenos Aires in October 1870; there the circus hosted a political meeting in homage to France, which was at war with Prussia. The records are often sketchy (indeed, it was not easy to follow such an intrepid world traveler at a time when international communications were not simple), but in June 1872, Chiarini landed in New York, arriving from Havana with his two-year-old Brazilian-born son, Giuseppe.

In September 1872, Chiarini's Royal Italian Circus performed in its hometown, San Francisco, before a tour of California and the Midwest, and a halt in Chicago. At that time, Giuseppe secured the services of Joseph Andrew Rowe (1819-1887), an American circus entrepreneur who, like him, was well known in San Francisco and Latin America. Rowe had toured the Far East and Australia in 1852, and with him and another associate, J. P. O’Neill, Chiarini prepared his first visit to New Zealand and Australia.

First Trip To Australia And The Far East

Chiarini’s company landed in Melbourne in March 1873, arriving from New Zealand, where they had done excellent business. The Royal Italian Circus boasted 62 horses and 150 employees—although records of the performance mention only thirty performers, and twenty seven horses and five ponies. But, notwithstanding the traditional circus ballyhoo, it must certainly have been an impressive ensemble, which indeed Chiarini’s circus was.

In June, after a successful run in Melbourne, Chiarini moved his operation to Sydney. Its large and luxuriously appointed "pavilion" didn’t fail to impress the locals: It was 175 feet in diameter, with a canvas roof (the sidewalls were probably made of wood panels) supported by a single central pole in the middle of the ring, and eight large quarterpoles. The troupe included such regulars as seventeen-year-old Katie Holloway (who had married the equestrian acrobat, George F. Holland, the previous year), and the equestriennes Berien and Theodora Cuba (Cuba was now their stage name).

George Holland, a remarkable somersaulter on horseback, was also in the company, along with Mr. Rowland, horse trainer; Edward Rowland, clownGeneric term for all clowns and augustes. '''Specific:''' In Europe, the elegant, whiteface character who plays the role of the straight man to the Auguste in a clown team.; Emilia Bridge, equestrienneA female equestrian, or horse trainer, horse presenter, or acrobat on horseback.; J. Fallon, strongman; George Worland and Adolph “Chili” Gonzales, tumblers (the latter remained in Australia afterwards); the Carlo Brothers, versatile performers who did a risley act as well as a musical act; Henry Dorr, gymnast on the horizontal bar; and the "trapezienne," Miss Gracie, queen of the iron jawAerial trick in which a performer hangs from a small apparatus fitting in his/her mouth (a ''mouthpiece'' — French: ''mâchoire'') and hooked to another apparatus or piece of equipment..

Some disagreements seem to have occurred within the company at the end of the Sydney engagement; several performers, among whom George and Katie Holland and J. A. Rowe, left Chiarini and returned to the United States. Giuseppe reorganized his company, and sailed to Batavia (today Jakarta), in India. The circus subsequently performed in Singapore, before opening in Bombay (today Mumbai) on November 20, 1874—the first of several appearances there, which inspired Vishnupant Chatre, Riding Master at the court of the Rajah of Kurduwadi, to create an indigenous Indian circus.

Back To The Americas

One month later, on December 21, 1874, Chiarini opened in San Francisco, at the Amphitheatre erected on New Montgomery Street earlier that year by John Wilson (1829-1885)—another San Francisco circus entrepreneur and pioneer (and a fellow world traveler), who had started showing in the city in 1859. Apparently, Chiarini had just arrived from China the day before, via Manila and the Philippines. Considering the time frame, the Great Italian Circus probably didn’t perform much, if at all, in these countries, but Chiarini brought back with him a troupe of Japanese acrobats.In 1875-1876, the Royal Italian Circus was in Brazil, which it toured extensively; the business proved excellent, and the circus even performed for Emperor Dom Pedro in Rio de Janeiro. By this time, Chiarini had began to trade horses and to add exotic animals to his show, which would much impress his audiences in the remote countries he visited—where many of these animals were rarities, if not simply unknown. (He had notably a giraffe, which is recorded to have died during his Brazilian tour.)

Then he visited Peru, where he was in September 1878, and probably continued North through Central America and Mexico. Finally, in August 1879, Chiarini was back in San Francisco, where he performed under his big topThe circus tent. America: The main tent of a traveling circus, where the show is performed, as opposed to the other tops. (French, Russian: Chapiteau). According to descriptions published at the time, it was a luxurious, European-style one-ring affair, a vast round top, with boxes around the ring, followed by a section chairs and then a section of benches—an arrangement that was prevalent in Europe, whereas in the United States, traveling circuses were leaning toward gigantic proportions and Spartan comfort. Chiarini’s tent could accommodate 3,000 spectators, and was luxuriously appointed, with drapes and carpeting, and lit by big chandeliers.

The detailed program of this engagement is known, and worth describing. It began with a musical overture, Franz von Suppé’s Light Cavalry Overture, by the circus band led by Joseph Green. A Grand Entry, The Queen’s Musketeers, followed this: "Four ladies and four gentlemen on splendid horses," led by Chiarini himself. Then, "La Perche Equipoise" (a perch-poleLong perch held vertically on a performer's shoulder or forehead, on the top of which an acrobat executes various balancing figures. act) was presented by Dunbar & Bartolo, before the "Principal Somersault Equestrian Act" of Lavater Lee. A Chilean colt, Garabadi II, was "introduced by Miss Nellie Reed," and Fred SyIvester (a Franconi’s Hippodrome’s alumnus) presented a couple of trained zebras.

Miss Rosa Lee came next, juggling clubs while standing on the back of her trotting horse; the clowns Lehman, Siegrist & Durand provided comic relief with their "entrée(French) Clown piece with a dramatic structure, generally in the form of a short story or scene. comique," and were followed by Dave Castello with a waltzing horse. Miss Nellie Reed, "the English Amazon," presented in haute-école(French) A display of equestrian dressage by a rider mounting a horse and leading it into classic moves and steps. (See also: High School) (dressage) the crown jewel of Chiarini’s stables, Abd-el-Kader; her encore was followed by the aerial act of Miss Fergus & Signor Ceballos.

Miss Jeanette Watson performed another equestrian act, Victorelli & CardeIlo (Walter Victorelli and Charles W. Cardello) showed their acrobatic talents on the horizontal bars, and the "Educated Prussian Stallions, Prince & Duke," were introduced by Signor Chiarini himself. Fred Watson performed "Laughable Equestrian Lightning Changes" (probably in the manner of Andrew Ducrow), and Chiarini returned, riding his jumping horse, Monte Christo.

The finale was an exhibition of "Leaps and Somersaults" performed by the entire company. As an added attraction(Russian) A circus act that can occupy up to the entire second half of a circus performance., there was an after-show of sorts, a group of "Royal Bengal tigers" handled by George Watson: This act—or, more accurately, exhibition—was presented in a large cage wagon as was the custom then, and it was to become a staple of Chiarini’s performances around the planet for years to come.

Australasian Encore

After a tour of California and Nevada, Chiarini returned home and, on September 20, 1879, set sail for Auckland, New Zealand, where he arrived one month later with a company of 32 performers and employees. He hired the remaining personnel locally, since the Royal Italian Circus was later reported to have a total of 75 persons working for it. The menagerie included twenty-six horses; five Shetland ponies; two zebras; a bison; a guanaco; three tigers, and three cubs born en route to Auckland; and an apparently large collection of performing dogs.

The show was in large part similar to what he had presented in San Francisco, with a few changes of personnel. After Auckland, Chiarini performed in Nelson, Wellington, Wanganui, Christchurch, Asburton, and Timaru, before sailing to Australia. On land, the circus traveled on a special thirty-four cars train, including boxcars for the animals and equipment, and carriages for the personnel.

Chiarini opened in Melbourne in February 1880. After a successful season there, the Royal Italian Circus went on an extensive tour of Victoria, traveling on a twenty-eight cars train (the cars may have been larger than in New Zealand—unless the company, was obliged to share tighter quarters…). Then the circus went to Adelaïde and Tasmania, before sailing to Sydney, where it opened late May. From there, Chiarini toured New South Wales and Queensland.

The Royal Italian Circus left Australia some time in August 1880, and visited the Dutch East Indies (today’s Indonesia) and India, where it performed in Calcutta. Finally, at the beginning of the following year, the company returned to San Francisco, where Giuseppe tended to his business, refurbished his circus equipment, and renewed part of his cast in preparation for yet another tour of the Far East.

China And The Orient

In 1881, Chiarini’s circus visited India, Malaysia, Burma, Ceylon (today’s Sri Lanka), and Singapore—from where Giuseppe, who was performing there in June, reported a calamitous string of deaths in the company, among whom his tiger trainer, Charles Warner, of smallpox in Calcutta (he was replaced by Harry Ager); his boss canvasman(U.S.) In the traditional American circus, the person in charge of setting up and putting down the tents. Modern usage: Tentmaster., Andy Johnson, of cholera in Malaysia; and Mrs. Henry Charles Lee, the mother (or stepmother) of Lavater Lee, after giving birth to a son in Burma.In India, the circus traveled as usual by train. At the end of his Indian tour, in March 1882, Chiarini and his company set sail for Manila and the Philippines, then a Spanish colony, where the company performed as the Royal Spanish Circus, as it had done long before in South America. Then, Chiarini and his troupe sailed to Hong Kong.

This was the start of a very successful tour of some of China’s major cities, where the visit of a circus was as rare and exciting an event as a company of Chinese acrobats would have been in Europe or America at the time. In China, the presentation of trained tigers was a wonder to behold, and exhibitions of horsemanship (notably bareback riding) were quite extraordinary to a population generally more accustomed to the stage presentations of acrobatic theater and Chinese opera.

After the Chinese tour, the Royal Italian Circus visited briefly French Cochin China (today’s Vietnam), went to Java, returned to Singapore and Burma, and then sailed to Bangkok, the capital of the Kingdom of Siam (today’s Thailand), where they gave command performances for the King of Siam, his court, and his numerous harem on October 16, 1882. The program included French & Angelo on the double trapeze; a trained zebra presented by Jose Romano; comic horseback riding by Signor Saroni (whose name was spelled Sarony in the program); the Japanese balancing act of Kichigoro and his son; the stallion Garibaldi, presented by Jose Romano; and the eccentric musical act of Eugene, Robert and Edward Faust, with their father Edwin.

After a ten-minute intermission, Mademoiselle Zazo performed on the trapeze; Ida and Charles Stoodley presented their "Equestrian Visions," followed by a comic intermezzo by Saroni; Miss Emma (Walhalla, née Stoodley) starred as the principal equestrienneA female equestrian, or horse trainer, horse presenter, or acrobat on horseback.; the Walhalla Brothers performed a clown entrée(French) Clown piece with a dramatic structure, generally in the form of a short story or scene.; and the British Faust family returned with their floor acrobatics act. The finale was a "steeplechase" with Shetland ponies mounted by monkeys.

The composition of Chiarini’s company changed regularly during these tours: Quite understandably, the novelty of touring exotic lands wore off quickly, and after a while, many performers just wanted to go home and did not renew their contracts—and a few, as we have seen, didn’t survive the tour. Furthermore, Chiarini remained in Asia and Australasia for eight long years; he didn’t return to San Francisco until the end of 1889.

Australia, China And Japan

The Royal Italian Circus made another visit to India before embarking on its final Australian tour, which lasted from late 1883 to the end of 1885, with a detour to New Zealand in the summer of 1884-85 (the winter season of the northern hemisphere). Giuseppe Chiarini had become quite a celebrity in these lands, and the press duly saluted his return after a three-year absence.Images published in the Australian newspapers show that his big topThe circus tent. America: The main tent of a traveling circus, where the show is performed, as opposed to the other tops. (French, Russian: Chapiteau) was now a modern, two-pole American tent—much stabler than a single-pole tent, and easier to set up. (Not to mention that it also allowed an open, pole-free ring!) The Stoodleys were still with the company, as well as the Walhalla Brothers, the Faust Family, and the aerial gymnasts French and Angelo. The British clown James Holloway, father of Chiarini’s former stalwart, Kate Holloway, had then joined the company.

At the beginning of 1886, Chiarini’s company visited Hong Kong and the Philippines, and sailed to Macao (then a Portuguese enclave in China), where they landed in May. Another successful Chinese tour ensued, interspersed by visits to Seoul, in Korea, and to Japan: The Royal Italian Circus was in Yokohama at the end July, and would also visit Nagasaki, Kobe, Kyoto, Osaka, and Tokyo. When the company requested permission to enter Japan, it listed an multinational group of Italians, Americans, Germans, Australians, French, British, Greeks, and Dutch—and thirteen men from Manila, who were the show musicians.

These Japanese stands were enormously successful. In November 1886, Chiarini and his company performed in Tokyo for the Emperor Mitsuhito and his court; it was the first time the Meiji Emperor had ever seen a circus performance, and he presented Chiarini with $5,000 in gold. The Meiji era (1868-1912) marked the opening of Japan to the West and the industrial world, and Chiarini’s visit was an event of importance: Japanese nobility, government officials, and businessmen feted the company, and the Japanese artists Yoshu Chikanobu and Masanobu Sakuradai issued wonderful prints of Chiarini’s performance—which are today much sought-after collectibles.

The company left China in October 1887, and sailed to Colombo, Ceylon, where they performed in December. This visit was followed by an extended Indian tour, during which the equestrian Charles Stoodley passed away, in April 1888 in Agra. Another visit of New Zealand and Australia was planned but never materialized. In 1889, Chiarini was back in China and Japan. Finally, at the end of that year, the indefatigable traveler returned home to San Francisco via Singapore and Honolulu.

The Final Years

Giuseppe Chiarini was now sixty-six years old. For exactly half of his life, he had managed a major circus, organized international tours in the most remote parts of the globe, transporting and taking care of a huge equipment, a large multinational company of first rate performers, and an important collection of animals, and exhibiting his equestrian talents at each and every performance. His age was catching him back, and his health was slowly failing. It could have been a good time to sell everything and retire—or at least slow down.

But it was not something the Italian-American impresario was willing to do. To be sure, he would not cross the ocean again, but in early 1890, Chiarini hit the road again, returning to Central and South America, which he had not visited since 1879. Under the Royal Spanish Circus title, he toured extensively Mexico, Argentina, Bolivia, Peru, Ecuador, Colombia, Honduras, and San Salvador for the next seven years.

In 1897, the circus was in Panama; Chiarini was seventy-three and had perhaps overestimated his powers: He fell ill, and died at the Hotel Americano, in Panama City, where he had established his quarters, “sometime in the middle of April 1897.” Chiarini, who had always lived from hand to mouth, reinvesting his gains in his circus or yet another voyage, died penniless.

Chiarini’s circus left a long lasting impression wherever it performed. The Australian circus historian Marc St. Leon noted that when, in the 1970s, he researched the American circuses that had visited Australia between 1850 and 1950, the name that always came first and foremost among Australian circus folks was that of Chiarini. Likewise, Indian circuses track their roots to the visits of Chiarini’s Royal Italian Circus to their country. Chiarini became a most respected name among audiences and circus folks all around the world.

Unfortunately, Chiarini’s circus died with Giuseppe. Giuseppe Chiarini had outlived his first wife, Giuseppina, and the children he had with her, Josephine and Giuseppe. His second wife, who died in Oakland, California, on September 8, 1932, gave him two children, Carlos and Abeli. They settled in Oakland, and didn’t continue the circus lineage.

Note On Sources

The name of Giuseppe Chiarini appears in virtually every published history of the circus. He is always singled out for his extensive and incessant travels around the world—with sometimes a word about his talents as a circus equestrian. But that’s about it. His life and career are always left in a shroud of mist: He is generally mentioned as an Italian circus director, although in that capacity, he was actually an American circus entrepreneur. And in spite of that, and the fact that he was a truly remarkable American circus figure, American circus history books rarely mention him, or do so only en passant.

A large part of the information given in this essay comes from the research of American circus historian Charles Gates Sturtevant, which he published in 1932 in a short article, Chiarini, Prince of International Showmen. Beside his personal research, Sturtevant spoke notably with two circus fans, James V. Chloupek, and S. R. VanWyck, "who were well acquainted with the late Mrs. Chiarini and her sons." (Chloupek had also published a short article on the life of Giuseppe Chiarini in the October 1932 issue of the magazine Circus Scrap Book.)

The Australian circus historian Mark St. Leon augmented significantly this research, notably with regard to Chiarini’s Australasian tours, and published his findings in great detail in his excellent book, Circus In Autralia – The American Century, 1851-1950. Other information collected in this article is scattered in various books and documents, and as in most historical research, is the result of patient "detective" work. Hopefully, it will be augmented (and probably corrected) in time. Yet a complete biography of this extraordinary circus entrepreneur remains to be written. — D. J.

Suggested Reading

- Signor Saltarino (Waldemar Otto), Pauvres Saltimbanques (Düsseldorf, Druck und Verlag von Ed. Lintz, 1891)

- Mark St. Leon, Circus In Autralia – The American Century, 1851-1950 (Penshurst, NSW, Mark St. Leon, 2007) ISBN 0-9593315-2-2