John Bill Ricketts

From Circopedia

THE FIRST CIRCUS IN AMERICA

By Dominique Jando

On April 3, 1793, a crowd of theatergoers, horsemanship enthusiasts, and prying citizens gathered at the corner of Market and Twelfth Streets in Philadelphia to witness the debut performance of Mr. John Bill Ricketts's company at the Circus. The Circus was a roofless arena of some eight-hundred seats (divided between pit and boxes) surrounding a circular riding space filled in with a mixture of soil and sawdust, forty-two feet in diameter—the ring.The wooden construction(French) A temporary circus building, originally made of wood and canvas, and later, of steel elements supporting a canvas top and wooden wall. Also known as a "semi-construction." had been erected in a matter of weeks by Ricketts, a British equestrian who had arrived from Scotland the previous year and had quickly established a riding school in Philadelphia, then the capital of the newly formed United States of America. Ricketts (1769-1802) had followed the example of Philip Astley, who had established just such a riding school in London in 1768, at the foot of Westminster Bridge, before creating there the first modern circus two years later.

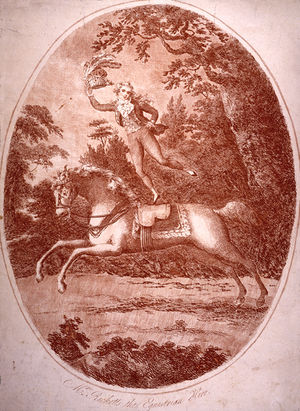

Before long, a small group of performers from Ricketts's former British company joined him in Philadelphia. Among them were his brother Francis, an equestrian and tumbler; Mr. Spinacuta, the rope-dancer, along with his wife, an attractive equestrienneA female equestrian, or horse trainer, horse presenter, or acrobat on horseback. who rode two horses at full gallop; Mr. McDonald, another tumbler who performed comic acrobatic intermezzos as the Clown; and Ricketts's pupil, young Master Strobach. The performance included a great many "feats of horsemanship," most of them presented by Ricketts himself, rope-dancing, some tumbling, and McDonald's acrobatic parodies. This was the first circus show ever put on in America.

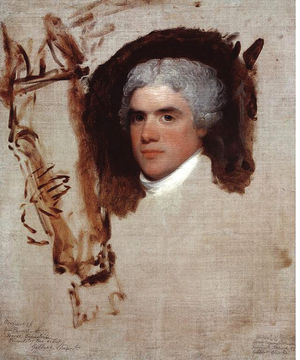

Young and good-looking, talented and enterprising, Ricketts became an instant sensation. But if his contemporaries have described his acts extensively, little is known of his life outside of the circus. Fortunately, Gilbert Stuart left a superb, if unfinished, portrait which is now in the collection of the National Gallery of Art in Washington, and John Durang, one of the first American actors—who worked for Ricketts as a dancer, equestrian, acrobat, clownGeneric term for all clowns and augustes. '''Specific:''' In Europe, the elegant, whiteface character who plays the role of the straight man to the Auguste in a clown team., scenic painter, and deputy manager from 1795-1800—has provided some hints of the man's character in his Memoir, composed circa 1820 (1).

Origins

John Bill Ricketts was born in October 1769 in Bilston, a small town near the city of Wolverhampton in the West Midlands, to Thomas Ricketts and his wife, Kinborrow, née Perry. His baptism was recorded on October 28, which suggests he was born a few days before. The Ricketts family, which was of Norman extraction and whose original patronymic was Ricard, had long belonged to the landed gentry of Staffordshire. At the turn of the eighteenth century, the elder branch settled in Jamaica, although several members of this very large branch of the family returned to England, either to study or to resettle; others established themselves in the colony of New Jersey in America. Thus Ricketts was not in alien territory when he landed in the newly formed United States. Neither would he be heading to unknown territories when, at the end of his American adventures, he sailed to the West Indies.

Before crossing the Atlantic, John Bill Ricketts had just begun to make his mark in the United Kingdom. A former pupil of Charles Hughes—Philip Astley's rival and the founder of London's Royal Circus—Ricketts was first noticed as the star equestrian of a troupe managed jointly by the actor-manager James Jones and the equestrian George Jones (no relation). The Joneses would later establish a permanent circus in Edinburgh, which their company had visited regularly. Jacob Decastro, Astley's and Hughes's first biographer, who saw Ricketts perform in Whitechapel with the Joneses, declared him "the first rider of real eminence" (2).

By 1791, John Bill Ricketts had formed his own circus company in partnership with John Parker, a dancer turned "equestrian manager" (i.e. circus manager), and they established themselves at the Circus Royal in Edinburgh—probably the Joneses' original amphitheater. Parker & Ricketts toured principally Scotland and Ireland, and many members of their company were fellow performers of Ricketts in the Joneses' circus company—several of whom would later join Ricketts in America.

Ricketts in America

George Washington attended at least one performance at Ricketts's Circus, on April 22, 1793. The Philadelphia season ended in July, at which time Ricketts, his company, and the horses he had recently acquired in Pennsylvania traveled to New York City, to a new circus Ricketts had erected on Broadway, near the Battery. As in Philadelphia, this first arena was roofless, and the performances were given in daylight, at four in the afternoon. The weather must have been clement that year, since Ricketts kept the circus open until the fourth of November before moving south to Charleston, South Carolina.

Ricketts and his company (whose composition varied from season to season) spent seven years introducing the circus to North America, venturing from South Carolina to the province of Québec. His homebase, however, remained Philadelphia, and most of his travels concentrated around New England and Virginia.In May 1794, Norfolk and Richmond, Virginia, saw their first circuses. In July, Ricketts was in Baltimore, "near the Windmill," and back to Philadelphia in September. In November, the industrious manager was in New York, where he opened a "new and commodious Amphitheatre" at the southwest corner of Broadway and Exchange Alley (then Oyster Pasty Lane). The new circus had a roof and was "superbly illuminated" with "upwards of 200 wax candles and Patent lamps," while "convenient stoves" provided some heating.

From May to July, Bostonians gathered at Ricketts's Equestrian Pantheon, which the showman had erected on the Mall (at what today is the corner of Tremont and Boylston streets). Then Rhode Island and Connecticut enjoyed their first circuses before the troupe attempted a return engagement in New York, unfortunately aborted by an epidemic of Yellow Fever.

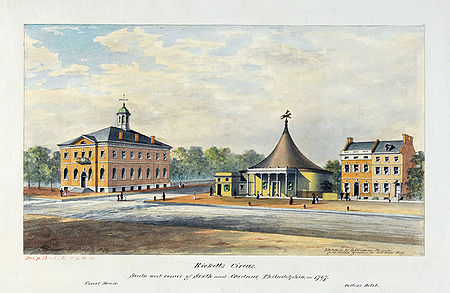

October saw the opening of Ricketts' Art Pantheon and Amphitheatre, a brand-new circus building erected at the corner of Sixth and Chestnut Streets in Philadelphia. The building was circular, 97 feet in diameter, with a capacity of 1,300 and a conical roof that reached 50 feet in height. In the manner of European circuses, the Art Pantheon was equipped with a ring for the equestrian displays and a theater stage for the performance of pantomimes and some acrobatic acts—a concept developed by Charles Dibdin, a prolific author of pantomimes, who had been the partner of Ricketts's mentor, Charles Hughes. Indefatigable, Ricketts opened a similar circus in New York in 1797, on Greenwich Street, north of Rector Street; he would eventually lease it to his only competition, British equestrian Philip Lailson, who had arrived in the United States from Sweden the previous year and would later travel to Central America.

In 1797, Ricketts sent a second company, led by his brother Francis, to Montréal, where yet another circus opened in August near Recollet Gate. The show, accompanied by musicians of the 60th American Royal Regiment, received such an enthusiastic response that it prompted Ricketts to maintain a circus there and to replace his wooden construction(French) A temporary circus building, originally made of wood and canvas, and later, of steel elements supporting a canvas top and wooden wall. Also known as a "semi-construction." with a new stone building (this, in turn, was prompted by a city ordinance requiring permanent buildings to be built of stone to prevent fires). Later, he sent the company to the city of Québec, where the second Canadian circus was built in May 1798, outside St. Louis Gate.

The Last years

On December 17, 1799, Mr. Miller, a circus carpenter, left a candle in the scenery storage-room of Ricketts's Pantheon in Philadelphia. The building caught fire and burnt to the ground. The conflagration badly damaged many adjacent buildings. This was a terrible financial blow for Ricketts. He tried to take the company to New York, where his circus was still standing, although the building had been put up for sale and had fallen into disrepair. The project proved too costly and failed to pan out. In April 1800, still stranded in Philadelphia, Ricketts finally settled in the once-elegant building erected by Lailson at the corner of Prune and Fifth Streets, the roof of which had collapsed two years before. While the audience was still covered, the performers were exposed to the weather and, so Durang tells us, "the lights in the night made a dim reflection which caused the performance to go off gloomy." The same could be said of the spectators, whose patronage dwindled.Disheartened, Ricketts resolved to leave the country. He chartered a small ship and, with some horses, his brother, a stable boy, a pupil, and Mr. Miller—his faithful, if calamitous, carpenter—he sailed to the West Indies. Once there, a series of uncanny circumstances followed involving French pirates, the shrewdness of Ricketts's groom, and the generosity of a Guadeloupe merchant. By year's end, Ricketts had managed to recoup his losses. He apparently went to the Island of Martinique, before selling all his horses "to great advantage" and set sail for England. Unfortunately, as Durang reports, "the vessel floundered and he was lost with all his money at sea." His death was registered by his mother in 1802 before the Prerogative Court of Canterbury.

Fifty years after Ricketts's departure, the circus had become America's most popular entertainment. American equestrians reigned supreme in the circus world. But they were no longer the managers Ricketts and his immediate successors had been. The circus developed into a lucrative business and, in some ways a victim of its own success, had been taken over by impresarios, entrepreneurs, and a fair number of artful swindlers who, given the itinerant nature of the trade, thrived. By then, the artistry of Ricketts's performances and the comfort of his amphitheaters had been supplanted by grandiose spectacles given under gigantic traveling arenas—so large, indeed, that the ring had to be multiplied, in order to give each spectator a chance to see some of the action under the elongated canvas. Eventually, the art form lost its identity in the process.

Reflecting on Ricketts's concept of his art, John Durang noted in his Memoir: "A circus within its own sphere, well regulated and conducted as Mr. John B. Ricketts established his in America, must succeed and please, and meet the admiration of the public and give general satisfaction."

Footnotes

1. The Memoir of John Durang, American Actor (1785-1816), edited by Alan S. Downer (Pittsburgh, University of Pittsburgh Press, 1966).

2. The Memoir of J. Decastro, Comedian, edited by R. Humphreys (London, Sherwood Jones & Co., 1824).

Suggested Reading

- John Durang, The Memoir of John Durang, American Actor, 1785-1816, edited by Alan S. Downer (Pittsburgh, The University of Pittsburgh Press, 1966)