Philip Astley

From Circopedia

Circus Owner, Equestrian

By Dominique Jando

Philip Astley (1742-1814) is considered the creator of the modern circus. He was born January 8, 1742 in Newcastle-under-Lyme, in the West Midlands, England, the son of Edward Astley, a veneer-cutter and cabinet-maker. Edward had a short-fuse and a passion for horses, traits he passed on to his son. Philip Astley was nine years old when he became apprentice to his father.

Two or three years later, the family moved to Lambeth, a borough of London, where Edward Astley opened shop near Westminster Bridge—an area that would become very familiar to young Philip, and where he will later return. For at age 17, Philip left home after one of many disputes with his father and enrolled in the 15th Light Dragoons, a cavalry regiment newly formed by Colonel Granville Elliott.

From The Military To Show Business

Six feet tall and endowed with a stentorian voice, Philip Astley was a giant for his time and didn't easily blend into crowds, even when in uniform. A gifted equestrian, he was put in charge of breaking new horses for his regiment. He was also noticed by the celebrated riding and fencing master, Domenico Angelo, who took him under his tutelage and taught him a new method aimed at improving the use of the cavalry broadsword in battle—an expertise Astley would later display in his shows.

In 1761, Astley and his regiment embarked for the Continent to fight alongside King Frederick II of Prussia in the Seven Years' War (1756-63), known as the French and Indian War in America. Corporal Astley fought gallantly: he captured an enemy standard in battle; rescued the Duke of Brunswick, who had fallen behind enemy lines; and returned to England with the rank of Sergeant Major. He obtained his discharge on June 21, 1766 at Derby, and Elliott, now General, presented him with a white charger named Gibraltar. Astley returned to Lambeth with a companion who would later become his wife (of whom little is known);in 1767, she presented him with a son, John Philip Conway Astley (1767-1821).

Trick-riding exhibitions were very popular in the second half of the eighteenth century. England had become a constitutional monarchy in 1688, and the spending power of the nobility had been curbed considerably. Private regiments were disappearing. Lavish equestrian court entertainments (such as carrousels) had ceased to be affordable. Private manèges staffed with riding instructors didn't fare much better. Still, riding masters, most of them coming from the military, could make a good living as trickAny specific exercise in a circus act.-riding performers (notably Jacob Bates, whose fame stretched from America to Russia). One of these trickAny specific exercise in a circus act. riders was Balp, a former cavalry Sergeant like Astley, who had opened a manege in Lambeth; Astley went on to work for him.

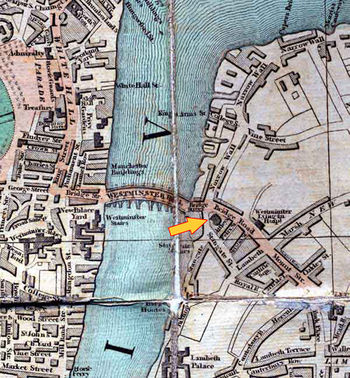

By 1768, Astley had secured a piece of land known as Glover's Halfpenny Hatch in Surrey County, south of London, between Blackfriars and Westminster bridges, where he had opened in the spring a riding school—a crude roofless enclosure where he taught horsemanship in the morning and performed in the afternoon during the summer season. He presented his "feats on horsemanship" on Gibraltar, and exhibited "The Little Military Horse"—a small horse he had trained to add and subtract numbers (or pretend to do so), feign death, fire a pistol, and perform "mind-reading" tricks. Like most trickAny specific exercise in a circus act. riders of his time, Astley performed in a circular arena: for the audience, it was easier to watch an equestrian circling in a well-defined area than to watch him dashing back and forth in a vast open space. For the riders, the centrifugal force generated by galloping in circles made it easier to stand on the back of their mounts. (Contrary to what is often said, however, Philip Astley did not "invent" the circus ring.)

The following year, in 1769, Astley secured a lease on a neighboring lot at the foot of Westminster Bridge, on the corner of Stangate Street and Westminster Bridge Road. Albeit roofless, the new Astley's Riding House was a more permanent wooden structure, and the audience at least was protected from the notorious London weather. The Riding House's arena (called either the "circle" or the "circus") had originally a diameter of 65 feet (about 19.5 meters). There, to the sound of fifes and drums, in good military fashion, Astley and some of his pupils offered afternoon performances of an exclusively equestrian nature. By the end of his first summer in the new location, Astley had reason to celebrate: His first two London seasons had been very successful. Yet he knew that if he wanted to establish a permanent place of performance that could attract London audiences over the long haul—especially the much-needed popular audience—he had to change the format of his show.

The Birth of the Circus

Following the disappearance of court entertainments, London had seen the development of a purely commercial theater, subsidized not by the nobility but by ticket sales. Whatever their specialty, theaters couldn't survive only on a handful of faithful patrons; they had to attract as large an audience as possible. Therefore, they had to please a diversity of tastes. With that in mind, Astley turned to the successful theaters of London (legit houses such as Drury Lane, Covent Garden, and the Haymarket Opera House, but also "secondary" houses such as Sadler's Wells) to find out what attracted the all-important popular section of their audiences.

All of them, he discovered, relied on visual acts (performances by jugglers, ropedancers, "posturers," as acrobats were then called, et al.), which, in the legit houses, were interspersed between the various theatrical offerings. (In the eighteenth century, performing arts were not yet segregated; actors, musicians, dancers, acrobats, and even equestrians all belonged to the same community of entertainers.) Additionally, theater performances were usually capped with "after-pieces," in most cases pantomimes, which, in England, were farcical spectacles with stage tricks and special effects and were the realm of Clown and Harlequin, the pantomimeA circus play, not necessarily mute, with a dramatic story-line (a regular feature in 18th and 19th century circus performances).'s principal stock characters.Therefore, the show Philip Astley offered at his Riding School for his 1770 London season was a mixture of equestrian and acrobatic acts, followed by a pantomimeA circus play, not necessarily mute, with a dramatic story-line (a regular feature in 18th and 19th century circus performances).. He had a crude stage erected in the ring for the visual acts and the pantomimeA circus play, not necessarily mute, with a dramatic story-line (a regular feature in 18th and 19th century circus performances)., and if the stage tricks were certainly limited, the farcical work of the clownGeneric term for all clowns and augustes. '''Specific:''' In Europe, the elegant, whiteface character who plays the role of the straight man to the Auguste in a clown team., originally a theatrical character, was a welcome addition to the performance. As Astley had expected, his new formula enjoyed immediate success. With that, a new form of entertainment had been created: the circus as we know it was born.

As in the theater, the extracurricular additions to Astley's show were just that, additions, and the performances at Astley's Riding School remained principally of an equestrian nature. But the great British actor and manager, David Garrick, who, as Astley was rising to fame, was at the eve of his brilliant theatrical career, had already planted the seeds of secession between the theater and other performing arts. To Garrick, whose work had been essential in bringing Shakespeare's plays back to the forefront of the British theatrical tradition, the exhibition of visual entertainers on a theater stage was a sacrilege: "nothing but downright starving would induce me to bring such defilement and abomination to the house of William Shakespeare." Eventually banned from the legit stage, visual entertainers would find in the circus a welcome and ideal refuge.

When not performing in London during the spring and summer seasons, Astley traveled. The success of his exhibitions led him to construct wooden amphitheaters all around the United Kingdom—which soon won him the nickname "Amphi-Philip." The first of these amphitheaters was erected in 1773 in Dublin, Ireland. The following year, Astley's son, John, had his first "benefitSpecial performance whose entire profit went to a performer; the number of benefits a performer was offered (usually one, but sometimes more for a star performer during a long engagement) was stipulated in his contract. Benefits disappeared in the early twentieth century." there as an equestrian—at age seven. (A "benefitSpecial performance whose entire profit went to a performer; the number of benefits a performer was offered (usually one, but sometimes more for a star performer during a long engagement) was stipulated in his contract. Benefits disappeared in the early twentieth century." was a gala performance whose entire profit was given to a performer; a benefitSpecial performance whose entire profit went to a performer; the number of benefits a performer was offered (usually one, but sometimes more for a star performer during a long engagement) was stipulated in his contract. Benefits disappeared in the early twentieth century. was often included in a star performer's contract)

Astley's Success

Inevitably, success brought competition. In 1772, one of Astley's former equestrians, the ambitious and talented Charles Hughes, opened his own Hughes' Riding School not far from Astley's, on Blackfriars Road. Hughes's show was practically a carbon copy of Astley's, and the competition became fierce, generating widespread interest and, consequently, good business. It also caught the attention of the Magistrates of Surrey County, who closed both shows in July 1773 because neither had secured the proper license to perform. Hughes then embarked on a long European tour, but Astley, who had just purchased his piece of land, secured a license for the next season and resumed his British tours. At the time, licensing issues constantly plagued theater entrepreneurs who lacked a Royal Patent–which was the vast majoruty of them. The patented theatres (Covent Garden, Drury Lane, and the Haymarket) made sure it remained so.

In 1774, Philip Astley performed his "feats of horsemanship" for the first time in Paris, at the Manège de Razade, rue des Vieilles Tuileries. The event is of some importance, since in the years to come Paris would become Astley's second home.

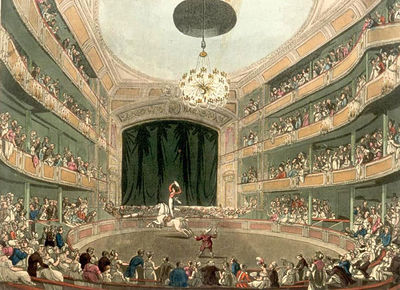

In the winter 1778-79, Astley added a roof to his amphitheatre, which allowed him to perform in the winter season and to give evening performances—to the annoyance of the London patentees, with whom he was now in direct competition. He reopened the house in January 1779 under a new name, Astley's Amphitheatre Riding House. The show offered the usual fare of equestrian and acrobatic acts, clowns and pantomimes, but Philip Astley didn't appear on the bill in his "feats of horsemanship." At age 38, he had retired from performing as a bareback rider, but remained with the show as its Equestrian Director, or, in modern terminology, its Ringmaster—a function he created for himself.

Astley vs. the Royal Circus

In 1781, Astley's old nemesis, Charles Hughes, returned to London after an eight-year tour of Europe. Hughes partnered with Charles Dibdin, a prolific songwriter and librettist. With the help of a syndicate of London backers, the two men began building a brand-new amphitheatre, this time in stone, on a piece of land located at the crossroads of the three thoroughfares leading to the three bridges serving London (Westminster, Blackfriars, and London Bridge). The place, known as St. George's Circus, had in its center an obelisk that was a well-known landmark. Again, Hughes had moved his operation into the vicinity of Astley's Amphitheatre.The Royal Circus, Equestrian and Philharmonic Academy—as it was pompously named (it would later be known simply as "Hughes' Royal Circus")—opened November 4, 1782. The first modern amphitheatre to bear the title "circus," it was an elegant structure whose ornate house included a fully equipped theater stage and a circus ring 36'6" in diameter (about 11.15 meters). The idea, in the words of Dibdin, was that "the business of the ring and the stage might be united." The configuration provided a way to give a more prominent place to pantomimes (Dibdin's specialty), but with the addition of an equestrian element that would eventually lead to the development of circus "hippodramas." The stage and ring arrangement devised by Dibdin and Hughes became the standard for practically all circus buildings until the second half of the nineteenth century.

With the success of Hughes' Royal Circus, Astley lost his monopoly. Thereafter, he had to contend with serious competition. Luckily for him, neither Dibdin nor Hughes were fiscally competent, and the group formed by the two directors, the circus's shareholders, and their landowners—the West family—proved to be incredibly dysfunctional. Hughes died at the end of 1797. By then the West family had repossessed the Royal Circus and, in 1794, leased it to James Jones and George Jones, whose company had included for a while John Bill Ricketts, a talented pupil of Charles Hughes who was to open the first American circus. Between 1781 and 1794, the Royal Circus had been racked by ceaseless internal feuds (Dibdin was forced out in 1785), plagued by licensing problems and near-bankruptcies, and gradually fell into a state of disrepair. In 1804, a fire badly damaged the building. After extensive renovations, the Royal Circus focused mostly on theatrical offerings. In 1810, it was converted into a full-fledged theatre.

Astley Expands

Throughout this period, Astley had no difficulty retaining his supremacy in the nascent circus business. On July 5, 1782, he opened the Manège Anglois (the old French spelling for "anglais"), a roofless enclosure on the Boulevard du Temple in Paris. He left Paris at the end of August, having met with considerable success—thanks in large part to his son, John, who had become the true star of the show. Astley returned to the same location the following summer, and John Astley was commanded to perform at the court of Queen Marie-Antoinette at Versailles. The performance resulted in the issuance of a Royal Privilege enabling Philip Astley to open a permanent amphitheatre in Paris. He purchased the lot where he had performed for two summers and there built a wooden amphitheatre, with an address at 16 rue du Faubourg du Temple, practically at the corner of the Boulevard. The Amphithéâtre Anglais des Sieurs Astley, père et fils opened its doors on October 16, 1783.

Philip Astley was now running simultaneously, with the help of his son, two permanent amphitheatres in two different capitals—and he would soon obtain a Royal Patent for a third ampitheatre, this one in Dublin, Ireland, which he erected on Peter Street. It opened in 1789. That same year, the French Revolution forced him to vacate his Parisian amphitheatre, which he leased to various theater companies and, starting in 1791, to Antonio Franconi, the Italian "father" of the French circus. Despite the permanent performance spaces, Astley's circus company still regularly toured the United Kingdom, laying in temporary wooden structures, which sometimes became semi-permanent provincial bases.

Astley's New Amphitheatre of the Arts and the Olympic Pavilion

When the war between the United Kingdom and revolutionary France broke out in 1793, Philip Astley, who was 51 years old, reenlisted in the 15th Light Dragons, "acting as a horse-master, celebrity morale-booster and war correspondent in one." On August 16, 1794, while he was serving abroad, Astley's London amphitheatre burned to the ground. It had been refurbished in 1786, with a proper stage (albeit far from the size of the Royal Circus's true theater stage) and the sylvan decoration, replete with false foliage, that Astley had already used in his Parisian amphitheatre. The revamped building had been christened Astley's Royal Grove.The Royal Grove was no more. Astley quickly obtained his discharge from the military and returned to London to rebuild it. This was done in record time: Astley's New Amphitheatre of the Arts was ready for the 1795 season, which commenced, as usual, on Easter Monday.

In 1802, after the Peace of Amiens, Astley returned to Paris and regained possession of his amphitheatre on Rue du Faubourg du Temple. The following year, his new London amphitheatre was again consumed by a fire. This was unfortunately the fate of many theatres at the time. Mostly built of wood, with stage areas doubling as storage space for highly flammable wood-and-painted canvas scenery, props, and even fireworks, the buildings were lit by open flames. Perhaps it is more surprising that they survived at all than that they burned down so frequently.

The Amphitheatre was rebuilt again in 1803, this time following the now-classic model of Hughes's Royal Circus, with a house lavishly decorated by the famous Scottish scene painter John Henderson Grieve, and a full theatre stage, which was said to be the largest in London. That same year, Philip Astley, who had practically reached the status of living legend, was commissioned to design a fireworks display on the Thames for King George III's birthday.

Astley was now more than ever in royal favor. In 1805, he obtained a license to build yet another circus, this time in London proper, at the corner of Newcastle and Wych Streets, in the Strand. The Olympic Pavilion opened on September 18, 1806. It was a substantial building, equipped with an equestrian ring reportedly wider than those of Astley's or the Royal Circus, and a full theatre stage. But Astley's new circus was hastily built, and never really took off. It changed name, look, it became a theatre—nothing helped. Astley lost a considerable amount of money in this last venture. He sold the Pavilion in 1813.Philip Astley died from stomach ailments in his Parisian home, Rue du Faubourg du Temple, on October 20, 1814. He was seventy-two years old. He was buried at the Mont-Louis Cemetery in Paris (today the Père Lachaise Cemetery, where his grave, unfortunately, is no longer visible). His will asked that all his Parisian properties be sold and for the proceeds to go to his son, John, who also inherited the amphitheatre at Stangate Street. John Philip Conway Astley survived his father by only seven years.

On November 1, 2015, a life-size statue of Philip Astley by the sculptor Andrew Edwards and the members of the Royal Doulton School of Sculpture was unveiled at the Newcastle-under-Lyme College's Performing Arts Centre in Newcastle-under-Lyme, Astley's birthplace—a long overdue tribute to a major figure in the history of Performing Arts. Three years later, on April 4, 2018 (Easter Monday, which was traditionally the beginning of Astley's London season), a plaque was unveiled in Waterloo's Cornwall Road in Lambeth, London, not far from the original location Halfpenny Hatch, home to Astley's first Riding School, to mark the 250th anniversary of the creation of the modern circus by Philip Astley. Then, on May 4, 2018, for World Circus Day, another monument was unveiled in Newcastle-under-Lyme, on St. George Street (on the boudary of Newcastle-under-Lume and Stoke on Trent), in presence of Zsuzsanna Mata, Executive Director of the Fédération Mondiale du Cirque, to honor once more Philip Astley and the creation of the modern circus.

Suggested Reading

- Jacob Decastro, The Memoirs of Jacob Decastro, Comedian (London, Sherwood, Jones & Co., 1824)

- Maurice Willson Disher, Greatest Show On Earth (London, G. Bell and Sons, Ltd., 1937)

- Mike Rendell, Astley's Circus — The story of an English Hussar (CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2014) — ISBN 978-1490496887

- Dominique Denis, Philip Astley — La naissance du Cirque (Aulnay-sous-Bois, Arts des 2 Mondes, 2018) — ISBN 978-2-915189-35-3

- Dominique Jando, Philip Astley & The Horsemen who invented the Circus (A Circopedia Book, 2018) — ISBN 978-1984041319

- Steve Ward, Father of the Modern Circus "Billy Buttons" The Life and Times of Philip Astley (Barnsley, Pen & Sword Books Ltd., 2018) — ISBN 978-1-52670-687-4

- Karl Shaw, The First Showman – The Extraordinary Mr Astley (Stroud, Amberley Publishing, 2019) — ISBN 978-1-4456-9549-5