Oskar Hoppe

From Circopedia

Circus Director

By Raffaele De Ritis

In the intricate chaos of post-WWII Germany, a number of minor German circus entrepreneurs (such as Emil Wacker, Kurt Collien, Willy Aureden, and Fritz Mey) rose from administrative positions they had held before the war, when the German itinerant circus was in its golden age, to a modicum of celebrity as new circus owners. Managing their way out of a difficult past, they ventured into various and sometimes interesting circus experiments with diverse fortunes. Among them, the opportunistic Oskar Hoppe proved to be particularly tenacious in his attempts to revive great names of the past by taking good advantage of the struggle of some old circus luminaries to stage a comeback.

Beginnings

Oskar Hoppe (1898-1969) was the youngest of a family of sixteen children. Although his father didn’t come from the circus world, his mother belonged to an old traveling family. Oskar went to work (and learn) in the Wille family’s circus, a small enterprise where he quickly showed an aptitude for, and interest in, the administrative part of show business. He married Kathe Kuhlen, a circus tight wireA tight, light metallic cable, placed between two platforms not very far from the ground, on which a wire dancer perform dance steps, and acrobatic exercises such as somersaults. (Also: Low Wire)-dancer, when he was quite young and, in the early 1920s, began to work as an administrative accountant for the circuses of Alfred Schneider and Willy Hagenbeck, and by 1935, for the new Circus Barlay of Harry Barlay and his wife Carola, née Althoff.

From Circus Barlay, he went on to manage Dominik Althoff’s circus. Dominik Althoff (1882-1974) had just given the direction of his enterprise to his children, Franz and Carola (who had quickly separated from Harry Barlay). While there, Oskar Hoppe, who had divorced his first wife, married Dominik’s daughter Helene (1907-1997). Then, in 1939, Helene and her bother Adolf (1913-1998) decided to go their own way and created the Circus Geschwister Althoff, the administration of which Oskar Hoppe, as usual, managed. But this association didn’t last long: By 1940, Helene and Adolf parted ways, Adolf going on tour with his own Circus Adolf Althoff, and Helene and Oskar with their new Helene Hoppe Circus. One may safely surmise that the meddling presence of his brother-in-law in the family combine didn’t thrill Adolf Althoff!During the war, Hoppe was prudently hiding behind her wife's name: As the circus’s principal, he was not in the Nazi regime's good graces since he had helped Jewish families leave the country through strategic tours abroad. (His wife, however, was equally at risk!) Circus Helene Hoppe was in Luxembourg in 1944, when the country was liberated by the U.S. Army. Hoppe made sure his attitude during the war would serve him: In 1945, back in Germany in the French-controlled territories, Hoppe's circus was one of the first to get a performing license and it regularly performed for the occupying troops—while other German circuses had still to fight suspicion of Nazi complicity. As a result, when, in 1946, Germany's circus owners created a professional union, Oskar Hoppe was named its president.

Post-War Missed Opportunities

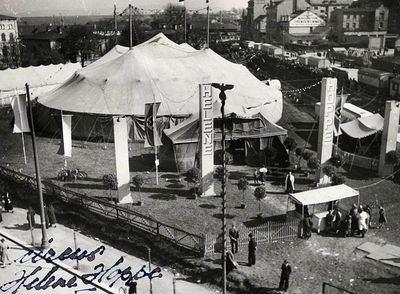

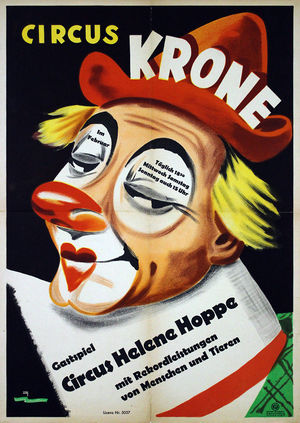

His good relations with the Allied Forces brought Hoppe a new opportunity, albeit briefly. The powerful Krone family was suspected of having collaborated with the Nazi party (like many German businessmen, Carl Krone had adhered to the NSDAP): While an investigation under way, their circus building in Munich, the Kronebau, was temporarily confiscated. Its management was assigned to Oskar Hoppe, who made it the home of his Circus Helene Hoppe from August 1946 to November 1947. Eventually, the Krone family was exonerated and repossessed their building. It has been rumored that, during Hoppe's occupation of the Kronebau, Frieda Krone, whose father, Carl Krone, had died in 1943, had to fend off Hoppe's propositions of marriage, which, as he saw it, would have allowed her to regain control of the family circus—and, of course, would have given Oskar Hoppe control of the Krone empire.Deprived of the Kronebau, Hoppe, who didn't have the means to resume regular circus tours, reverted to a temporary solution: He installed his big topThe circus tent. America: The main tent of a traveling circus, where the show is performed, as opposed to the other tops. (French, Russian: Chapiteau) in the Frankfurt Zoo, as a permanent attraction(Russian) A circus act that can occupy up to the entire second half of a circus performance., still under the title "Circus Helene Hoppe". But his marriage ended in 1948, and Helene Althoff went on to marry Hans Kossmayer, with whom she revived Emil Wacker's Circus Apollo that had gone bankrupt in Rome in 1952, keeping Wacker as an employee. (Unfortunately, the venture ended again in bankruptcy in 1958.)

After Helene's departure, Oskar Hoppe renamed his circus Circus Hoppe. Then, in the spring 1948, the popular Der Spiegel magazine reported a troubling chain of events at the zoo: animal poisonings, nightly beating of employees, anonymous menaces and allegations that the zoo's Director, Bernhard Grzimeck, a rival of Hoppe, had been a Nazi. Grzimeck had to resign his position. It was then discovered that Hoppe had filed a request for Grzimeck's position the day before his resignation. Hoppe dismissed the whole affair, as well as his interest in Grzimeck's position; then, the zoo's CEO declared he had filed the request without Hoppe's knowing. Grzimeck was eventually exonerated of all charges and reinstated, and he led the zoo until 1974, becoming a leading conservationist and an influential writer in the field.

That same year, 1948, Oskar Hoppe married for the third time. His new wife was Augusta Holzmüller (1907-1981), the daughter of circus director Josef Holzmüller (1872-1947) and sister of Willy and Max Holzmüller, circus directors and renowned elephant trainers.

The Paula Busch Affair

In the early 1950s, even though she had lost her entertainment empire, Paula Busch (1894-1973) was still considered the Grande Dame of the German circus, both for her charismatic personality and her unabated determination to keep her household name alive. At the end of the nineteenth and the beginning of the twentieth centuries, her father, Paul Busch (1850-1927), had been Germany's (and Europe's) most powerful circus director. He had created a network of major circus buildings (Berlin, Breslau, Hamburg, Vienna), inherited in part from the former Renz empire, set new standards for lavish circus productions and, with the help of his daughter, had produced the most theatrically elaborate pantomimes in circus history.

Paula Busch, who inherited her father's empire as well as his talent, was an accomplished director, an immensely successful producer, a published author, and a society lady. She had been an unintended victim of the rise of Nazi Germany: The Third Reich's urbanization plans for the new Berlin led to her Berliner building’s closing in 1934, followed by its demolition in 1937. Since she had adhered to the NSDAP, to “compensate” her loss, the Nazi government had facilitated her purchase of the Jewish Circus Strassburger, one of Germany's largest and most prestigious circuses. It was renamed Circus Busch-Berlin to distinguish it from the other traveling Circus Busch of Jakob Busch (no relation), which became known as Circus Busch-Nürnberg.The operation had been orchestrated by Emil Wacker, Circus Strassburger's manager and a member of the Nazi party. Wacker, who married Paula's daughter, Micaela, in 1936, remained as manager of the new Circus Busch under big topThe circus tent. America: The main tent of a traveling circus, where the show is performed, as opposed to the other tops. (French, Russian: Chapiteau). Still, Paula Busch would be soon accused to run a "Jewish circus" and to harbor Jewish performers (which she did). At the end of the war, nothing was left of the former Busch empire; all its buildings had disappeared under the Allies’ bombings, and Paula’s giant big topThe circus tent. America: The main tent of a traveling circus, where the show is performed, as opposed to the other tops. (French, Russian: Chapiteau) had long been folded and lost.

In 1946, she managed to set up an outdoor circus in the Berlin Zoo, called Arena Astra; then she was finally able to secure a loan and put together a new Busch-Berlin big topThe circus tent. America: The main tent of a traveling circus, where the show is performed, as opposed to the other tops. (French, Russian: Chapiteau) in 1952: She staged a true comeback, which was warmly welcome. Oskar Hoppe (now married to his fourth wife, Apollonia – 1923-1965), who had been observing Paula Busch' struggles, sensed a good opportunity. In 1953, with no remaining circus of his own, he managed to be hired by Paula Busch as administrator of her new circus.

Hoppe planned a tour, but with a weak itinerary (considering the German situation at the time, a good selection of towns that could sustain a circus visit was vital) and a modest program without animals. It was a complete fiasco. In her memoirs, Paula Busch said Hoppe’s was a purposely "miserable" plan, which of course had complicated her financial situation. The following year the equipment was rented out in The Netherlands to an ice show, which promptly went bankrupt. Paula's only way out of her troubles was the prospect of her daughter Micaela's imminent comeback with a second Circus Busch, which ventured in the Far East, and unfortunately ended bankrupt in Manila in 1954.

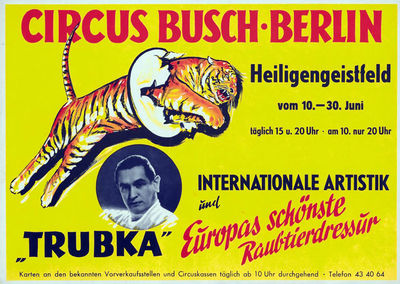

Hoppe was now ready for his move. He offered Paula Busch to rent her equipment and name, and operate the circus on his own, in exchange for a percentage of the receipts. Thus, in 1954, the "Circus Busch-Berlin – Direction Apollonia and Oskar Hoppe" hit the road. This time, the circus had a first-class itinerary and a more convincing program. Hoppe missed no occasion to celebrate his own success in the trade press and within the circus community. In 1955, he organized a "70th Anniversary Tour" (adding a year to the date of Circus Busch's beginnings), with a program that included Vojtech Trubka and Circus Knie's tigers and the Flying Leotaris. Hoppe's son, eight-year-old Ossy, presented the elephants and was billed as the "World's youngest elephant trainer."Unfortunately, Paula Busch’s side of the partnership was increasingly deteriorating. Hoppe was said to deduce money from her percentage, and he gradually bought out most of her circus equipment (which he had left in bad condition) at its lowest value. Finally, in 1958, Paula stopped leasing her name to Hoppe. She started a new "Busch-Berlin" partnership with circus director Karl Lagenfeld, the former owner of Circus Aeros, which had been nationalized and absorbed by the VEB Zentral-Zirkus, East Germany’s State Circus company. The new Circus Busch-Berlin opened in 1960 but went bankrupt two years later. The name was promptly saved by a good circus director, Willi Aureden of Circus Roland, who renamed his circus Circus Busch-Roland; the circus acquired an excellent reputation and enjoyed a long career, worthy of Paula Busch’s illustrious name.

Meanwhile, Hoppe had not easily let the Busch name go: He had found a legal way to keep his circus working under the title "Original Busch-Berlin." To complicate things, a third Circus Busch was traveling Germany: The Circus Busch-Nürnberg of the late Jakob Busch, now part of the East VEB Zentral-Zirkus company. In 1961, Hoppe's Original Circus Busch-Berlin, which claimed to be "the only real Busch," went on tour in Yugoslavia, but German shows were not welcome in that country, and Hoppe had to quickly reorganize a tour in Austria, in collaboration with the local Circus Rebernigg; then he spent the winter season at Brussels' Cirque Royal building. It had become clear by then that returning to Germany to be just another Circus Busch could be a problem. Always the opportunist, however, Oskar Hoppe had already spotted another old glory in distress.

Willy Hagenbeck's Struggles

After WWII, Willy Hagenbeck (1884-1963), was still viewed as a living circus legend by the public, as well as by the press and the German state authorities. The son of Wilhelm Hagenbeck—a true circus pioneer to whom circuses owe the removable circular steel arena, and the first trainer to present large polar bear groups—Willy had twice attempted to run his own circus between the wars, when he was not just attaching his own name to other companies, or renting out his animal groups.

In the 1940s, taking advantage of his various zoos and animal farms, he was mostly active in preparing acts and forming dozens of distinguished trainers, some of whom became very influential animal trainers (such as Henk Luycx, Jean Michon and Charlie Baumann). In 1947, his stepson, Erie Klant, had established what became known in the business as the "Hagenbeck training school" in Cauberg, in The Netherlands. Yet, Willy and his wife, Eugenie Klant, were still hoping to recreate a Circus Willy Hagenbeck. They found the opportunity in 1951 in a deal with Austria's Circus Konrad, which went under the name "Willy Hagenbeck" the following year.But the couple was aging, and Willy didn't have much business savvy; they attempted to bring Erie Klant into the combine, but Klant was happy with his flourishing animal training business and declined the offer (and its connected debts). By the end of the 1950s, Willy Hagenbeck's circus was in trouble. The old man managed to make some money by renting out his name and a few animal acts and menagerie features through Emil Wacker (who had become an agent). Wacker arranged for him a Circus Willy bHagenbeck-Liana Orfei in Rome during the 1961-1962 winter season, and a tour with the French Cirque Francki ("Francki présente: le Cirque Willy Hagenbeck") for the 1962 season.

Oskar Hoppe had observed the gradual weakening of Hagenbeck and his circus. Hoppe had a difficult past relationship with Hagenbeck: Before WWII, while he was working for him as a young accountant, Hoppe contributed to Willy's bankruptcy of 1931 by publishing in the trade paper Das Programm a lengthy document accusing him of insolvency, abuse of his employees and other niceties. Nonetheless, thirty years later, Hoppe took advantage of the failure of the Hagenbeck-Klant deal attempt, and promptly put his own circus at Hagenbeck's disposal.

By the spring of 1962, Hoppe's Original Circus Busch-Berlin was back in Germany under the title Circus Willy Hagenbeck. It was easy for Oskar to gradually buy Willy's old equipment, as he had done with Paula Busch, just giving a little percentage of the receipts to the old director. All this happened under the nose of Erie Klant, who realized he had missed the opportunity to save the glorious name of his stepfather and mentor. Sadly, it is in these circumstances that Willy Hagenbeck passed away in 1965—the same year as Hoppe's wife, Apollonia.

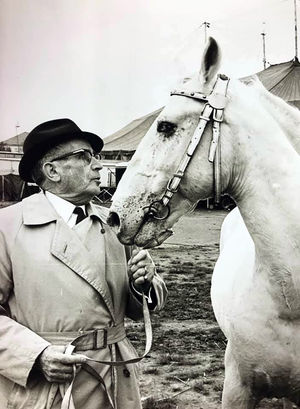

Circus Willy Hagenbeck had an acceptable life under Hoppe's ownership, without ever reaching the status level of the other German big names. Oskar managed to fill his seasons with an agreement with the Rumanian State Circus, and kept good animal trainers, such as Siegfried Wiesner (who had been with him since the Busch years) with his tigers, and Gerhard Braune, who presented the circus's horses and elephants. Oskar Hoppe would marry a fifth time, with Ingrid Pohle, who came from the medical field, before passing away in 1969, at age seventy-one.

Ingrid Pohle-Hoppe inherited her husband's Circus Willy Hagenbeck. She became a very competent and respected circus director. In an era that witnessed important changes in the German circus industry, often tempted by gigantism, Ingrid Hoppe brought her medium-size business to the peak of its reputation, with simple production standards, but with a good animal base and, often, world-class attractions. In 1978, her Hagenbeck-Hoppe circus was represented at the International Circus Festival of Monte Carlo with a 24-horse liberty"Liberty act", "Horses at liberty": Unmounted horses presented from the center of the ring by an equestrian directing his charges with his voice, body movements, and signals from a ''chambrière'' (French), or long whip. act presented by Gerhard Braune. In 1980, she changed her circus's title, which became Circus Ingrid Hagenbeck. Its life ended with Ingrid Hoppe's death in 1982.

Oskar Hoppe's Legacy

Several of Oskar Hoppe's children had brilliant careers in show business. Born of Oskar's first marriage with Kathe Kuhlen, Jean Albert Hoppe (1919-1979) created original farm animal acts that were quite successful; he was a long-time feature of Fritz Mey's Circus Sarrasani and appeared in some of the best European shows. He was also very active in training animals for movies and television. Born of Oskar's third marriage with Augusta Holzmüller, Helmbrecht Hoppe (1931-2009) developed an "unrideable mule" act that become immensely popular in the British circus and variety circuit, and had a good success on the continent. Oskar's fourth wife, Apollonia, gave birth in 1950 to Ossy (Oskar) Hoppe; after his early beginnings as a child elephant trainer during the Busch years, Ossy became Germany's top promoter of international rock concerts, a field in which he still is a recognized leader today.