The Schumann Dynasty

From Circopedia

Equestrians, Circus Owners

By Dominique Jando and Johan Vinberg

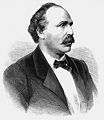

Founded by the German equestrian Gotthold Schumann (1824-1908), the Schumann Dynasty holds a prominent place in Scandinavian circus history and ran one of Europe’s most respected circus companies until the closure of the Danish Cirkus Broderna Schumann in 1969. They also have an important place in German circus history, especially through Gotthold’s son Albert Schumann, Sr. (1858-1939), who created his own circus and settled in (and then purchased) Ernst Renz’s flagship circus in Berlin in 1899—which remained active under Schumann’s ownership until the end of World War I.

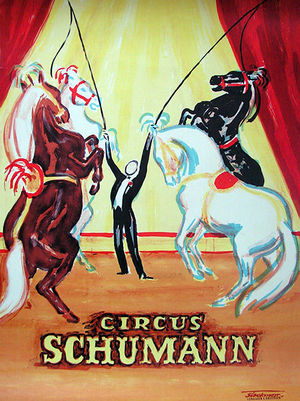

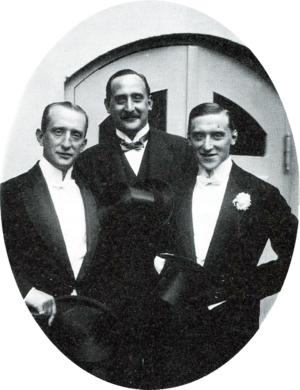

As circus equestrians, the Schumanns displayed a superlative talent and artistry; for five generations, they have maintained a commanding position in the circus world as horse trainers and high-schoolA display of equestrian dressage by a rider mounting a horse and leading it into classic moves and steps. (From the French: Haute école) riders. Albert Schumann, Sr. is widely acknowledged as having been his generation’s greatest liberty"Liberty act", "Horses at liberty": Unmounted horses presented from the center of the ring by an equestrian directing his charges with his voice, body movements, and signals from a ''chambrière'' (French), or long whip. horse trainer, and his Scandinavian nephews Willy, Ernst and Oscar, and later, Oscar’s sons Albert and Max, steadfastly preserved their family’s place in the equestrian circus’s firmament with exceptional brio.

The Founder: Gotthold Schumann

Gotthold Wilhelm Daniel Schumann was born on November 25, 1824 in Weimar, in the state of Thuringia, then part of the German Confederation. His father was a saddle maker, and Gotthold became indeed familiarized with horses at an early age. Although he was not interested in following in his father’s footsteps, horses were his passion, and he often helped groom and taking care of the neighbourhood horses. Gotthold had a brother who shared the same passion, Gustav.

Upon their father’s death in 1839, fifteen-year-old Gotthold and his brother Gustav joined the famous French company of Benoît and François Tourniaire, which was very popular in the German states since their father, Jacques Tourniaire (1772-1829), had established his company there at the beginning of the nineteenth century—before introducing the circus to Russia in 1825. Gotthold and Gustav became accomplished equestrians, as both bareback and high-schoolA display of equestrian dressage by a rider mounting a horse and leading it into classic moves and steps. (From the French: Haute école) riders, and Gotthold also developed a very good juggling act on horseback. In 1841, they were hired by Eduard Wollschläger (1811-1875), whose company included such future circus luminaries as Wilhelm Carré, Wilhelm Salamonsky and Heinrich Herzog.When Wollschläger’s future rival, Ernst Renz (1815-1892), created his own circus in 1845, he was joined by the Schumann brothers, who formed the bulk of the company together with Renz himself, his wife Antoinette, and a young equestrienneA female equestrian, or horse trainer, horse presenter, or acrobat on horseback. named Miss Adelina. But Renz’s enterprise quickly grew, and Gotthold became his Stable Master and principal horse trainer (that is to say, Renz's right hand), a position he kept for nearly two decades. Gotthold and his wife, Elise (of whom not much is known), had nine children: Max (1853-1933), Ernst, Albert (1858-1939), Adele, Louise, Adolf, Martha, Jacques (who became the circus’s music conductor) and Emil. Of Gotthold’s sons, only Max and Albert would truly make their mark in circus history, although Gotthold’s daughter Adele became a talented high-schoolA display of equestrian dressage by a rider mounting a horse and leading it into classic moves and steps. (From the French: Haute école) rider.

In 1863 or 1864 (the date is not sure), Gotthold finally created his own circus company, in partnership with a Swiss equestrian named Carl Antony. Unfortunately, in 1866, all their horses were requisitioned by the Prussian army, which was at war with Austria. Left without horses, which were the mainstay of all circus performances at the time, Gotthold’s venture came to an end. He restarted in 1871, this time in association with Heinrich Herzog, whom he had known when they were working together for Wollschläger. Circus Herzog-Schumann didn’t limit its tours to the German states: They expanded their route to Scandinavia.

Schumann and Herzog parted company in 1876. The Schumann family went on to work with other companies until 1879, when Gotthold created yet another circus with the equestrian August Krembser. It was a short-lived partnership, but Gotthold continued alone: The Circus Schumann that will eventually take its quarters in Copenhagen was born. Beside the German states and Eastern Europe (including Russia), its tours still included Scandinavia, notably Sweden which Gotthold’s son and successor, Max, will make his adopted country, and Denmark, where the family eventually settled.

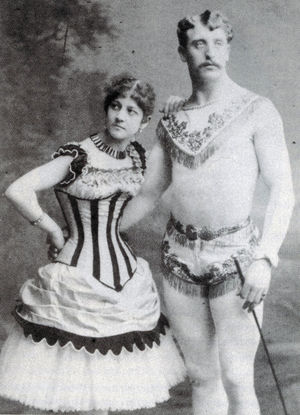

THE GERMAN LINE: ALBERT SCHUMANN

Albert Schumann, Gotthold’s third son, was the first of his children to truly make his mark in the circus world. He was born January 22, 1858 in Vienna, during a stay of Renz’s company in the first circus the German director had built in the Austrian capital, on Leopoldstadt. Albert began to ride at age three and became in time an accomplished equestrian, specializing as a bareback rider. He was twelve when he made his debut in the ring in a classic jockeyClassic equestrian act in which the participants ride standing in various attitudes on a galoping horse, perform various jumps while on the horse, and from the ground to the horse, and perform classic horse-vaulting exercises. act with a pony; later, he became an outstanding bareback rider "à la Richard"—a jockeyClassic equestrian act in which the participants ride standing in various attitudes on a galoping horse, perform various jumps while on the horse, and from the ground to the horse, and perform classic horse-vaulting exercises. act popularized by the American equestrian Davis Richards (1832-1866), in which the rider jumps over fences standing on the back of his horse.Albert, whose act became quickly one of the finest of its genre, was ambitious and well aware of his talent; in 1876, he left Circus Schumann and went to work on his own, followed in this statement of independence by his brother Max, who also went his own way. Ernst Renz, who had known Albert since childhood, hired him at a good salary—reported as 1,000 Francs a month, the equivalent of today’s 3,250 Euros, a comfortable sum then. Albert also performed with James Washington Myers in England, and then at Paris’s Cirque Fernando, where he revealed his outstanding abilities as a horse trainer when he presented for the first time a high-schoolA display of equestrian dressage by a rider mounting a horse and leading it into classic moves and steps. (From the French: Haute école) act: He had put it together in just two weeks!

Soon after, Ernst Renz secured the lease of Brussel’s brand-new Cirque Royal, on the rue de l’Université, for the 1878 season. The circus was slated to open January 12, 1878, and Renz (who was already sixty-three then, an advanced age at the time) asked Albert Schumann to procure him and train a complete cavalerie(French) The ensemble of the horses in an equestrian circus. for the occasion. Schumann not only proved that he was up to the task, but also confirmed that he was quite an exceptional horse trainer: Within twenty-two days, he got ready for the ring twenty-six horses, including a trio of horses that he had prepared for a high-schoolA display of equestrian dressage by a rider mounting a horse and leading it into classic moves and steps. (From the French: Haute école) act.

Albert Schumann returned to the family fold in 1882 and put together his first liberty"Liberty act", "Horses at liberty": Unmounted horses presented from the center of the ring by an equestrian directing his charges with his voice, body movements, and signals from a ''chambrière'' (French), or long whip. act for his father’s show. He was still working as a jockeyClassic equestrian act in which the participants ride standing in various attitudes on a galoping horse, perform various jumps while on the horse, and from the ground to the horse, and perform classic horse-vaulting exercises. at the same time—but not for long: He had a bad fall while performing with a partner a new bareback riding act titled "Athletes on Horse." He suffered internal injuries, which doctors diagnosed as a rupture of the diaphragm. They left him incapacitated for a few months—after which he was unable to resume his jockeyClassic equestrian act in which the participants ride standing in various attitudes on a galoping horse, perform various jumps while on the horse, and from the ground to the horse, and perform classic horse-vaulting exercises. career. From then on, he would specialize as a high-schoolA display of equestrian dressage by a rider mounting a horse and leading it into classic moves and steps. (From the French: Haute école) rider and in the training of remarkable liberty"Liberty act", "Horses at liberty": Unmounted horses presented from the center of the ring by an equestrian directing his charges with his voice, body movements, and signals from a ''chambrière'' (French), or long whip. acts, for which he became famous all over Europe.

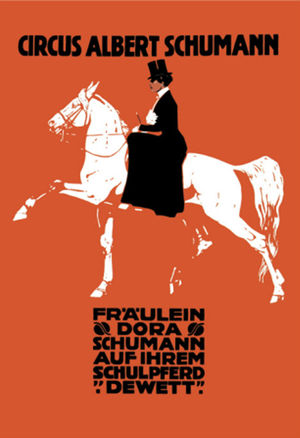

Circus Albert Schumann

When Gotthold’s circus ended its Swedish season in 1885 and returned to Germany, Albert, who had had an argument with his father over his salary, stayed behind and crated his own circus in Malmö in the South of Sweden. The show, which opened on May 16, 1885, was not big, and its quality was a little wanting at first, but Albert had sixteen horses that he trained in a matter of weeks and which gave his performances a solid backbone. Soon, Circus Albert Schumann would be celebrated for its equestrian presentations and pantomimes, the first of which, The Irish Bastion (1886), was hugely successful.Signor Saltarino (Valdemar Otto) described Albert Schumann in his book Artisten Lexikon (1895) as "a pleasant person in private life, free from vulgar self-admiration, and at the same time possessed by a real competitive spirit, which is unmistakably apparent in the management of his company." Indeed, Schumann had a strong personality with a fighting determination that would eventually drive his circus to the top in spite of the inevitable ups and downs of its beginnings. He married Clara Happe (1856-1929), with whom he had a daughter, Dorothea, known as Dora (?-1945), who became an accomplished high-schoolA display of equestrian dressage by a rider mounting a horse and leading it into classic moves and steps. (From the French: Haute école) rider.

Albert Schumann didn’t hesitate to travel far and wide. For this purpose, he purchased a large big topThe circus tent. America: The main tent of a traveling circus, where the show is performed, as opposed to the other tops. (French, Russian: Chapiteau) (still uncommon at the time and referred to as an "American tent"), so that his itinerary wouldn’t be contingent upon the presence or availability of a circus building in the places he chosed to visit. Warsaw, which was then within the Russian empire, had become a good market for him, but during a stand there, his tent was blown down by a tornado that destroyed practically all of his traveling equipment. Undeterred, Schumann hit the road again, and went to perform with great success in the circus buildings of Kiev and Odessa, where he was able to recoup much of his financial loss.

He made his first visit to Berlin in 1893, where he was in competition with Europe’s premier circus, Berlin’s own Circus Renz. However, his old mentor, Ernst Renz, the German "Circus King," had died on April 3, 1892, and his son, Franz (1841-1901), had succeeded him at the helm of his circus empire—which included, besides his Berlin flagship, circuses in Hamburg, Breslau (today’s Wrocław) and Vienna. Unfortunately, Franz Renz didn’t have the business acumen or the talent of his illustrious father and by the end of the decade, Albert Schumann would take over (and eventually purchase) the huge Circus Renz that Ernst had established in the former Markthalle on Karlstrasse, in Berlin-Mitte (Berlin Center).For the time being, Schumann was building his own circus empire. In 1890, he made his first visit to Vienna with his big topThe circus tent. America: The main tent of a traveling circus, where the show is performed, as opposed to the other tops. (French, Russian: Chapiteau). Then, in the winter of 1890-91, he had a wooden construction(French) A temporary circus building, originally made of wood and canvas, and later, of steel elements supporting a canvas top and wooden wall. Also known as a "semi-construction." erected on Märzstrasse, which was enlarged in 1892 by a carpenter named Otte to accommodate 3,500 spectators (or so proclaimed the advertising), and then rebuilt again in 1903—this time as a brick and mortar structure designed by the architects Heinrich and Franz Stagl, at a cost of 800,000 Crowns (approximately 308,900 Euros today). This new circus opened on April 9, 1904; it would remain active, alternating circus performances and variety shows, until its demolition in 1922.

In 1898, he had another circus built in Löbtau, southwest of Dresden, on Ebertplatz. It was a large building that seems to have had quite a significant success, although the massive bombing of Dresden at the end WWII destroyed whatever documentation that may have existed about its construction(French) A temporary circus building, originally made of wood and canvas, and later, of steel elements supporting a canvas top and wooden wall. Also known as a "semi-construction.", its existence and its programs. It was active until 1903, when Lötbau was incorporated in the city of Dresden—which ordered its demolition because the building didn’t comply with the city’s strict fire regulations. (Albert’s brother Max tried a few years later to re-establish the Schumann name in Dresden, but lost his bid to Hans Stosch-Sarrasani.)

The Fall of The Renz Empire

Albert Schumann was not the only empire builder, though, and Franz Renz faced now a huge competition: On his way to becoming Ernst Renz’s true successor as Germany’s "Circus King," Paul Busch (1850-1927) had built a circus in Hamburg-Altona in 1891, competing with Ernst Renz’s (and then Franz’s) well-established circus in Hamburg. One year later, Busch purchased the old panorama on Vienna’s Prater and transformed it into a 2,600-seat circus that opened on July 30, 1992—competing with Renz’s equally well-established circus in Vienna, on Zirkusgasse—as well as with Albert Schumann’s new Viennese circus.

The final blow came when Paul Busch built a 3,500-seat, state-of-the-art circus behind the Börse train station (today’s Hackescher Markt S-Bahn station), which opened its doors on October 24, 1895. Not only was Berlin’s Circus Busch equipped with all modern conveniences—including a water basin as in Paris’s Nouveau Cirque—and had the lure of novelty, but its programs were also particularly brilliant, thanks in part to the talent of Busch’s wife, Constance (1849-1898), who was the artistic force behind her husband, a talented equestrienneA female equestrian, or horse trainer, horse presenter, or acrobat on horseback. and a gifted actress in the circus pantomimes she staged—qualities that her daughter Paula will demonstrate later with even greater flair!Franz Renz had a hard time keeping up with the new competition: Although he offered circus programs of good quality, he didn’t have his father’s combative spirit nor his creative talent: Berlin’s fabled Circus Renz in the Karlstrasse’s old Markthalle gave its last circus performance on July 31, 1897. Franz Renz rented out the building to the famous Hungarian showman Bolossy Kiralfy (1848-1932), great international purveyor of spectacular extravaganzas, whose brother Imre (1845-1919) had created lavish spectacles in the United States on Broadway and for the Barnum & Bailey Circus in the late 1880s and early 1890s. Kiralfy’s tenure on Karlstrasse was not a success however, and Franz Renz had to find another tenant. Albert Schumann, who had done well in Berlin, took over the lease in October 1899; Berlin’s old Circus Renz acquired a new identity in the operation and was renamed Circus Albert Schumann.

The huge, 4,500-seat circus had been constructed in a former market—a spectacular structure of iron and glass designed by the architect Friedrich Hitzig, who had previously designed Berlin’s "Ottosche Circus" on Friedrichstrasse. Hitzig’s Markthalle had opened on October 1, 1867. It was an imposing building, 84 x 62 meters and 15.5 meters high (approximately 277 x 204 x 51 feet), which was located on a former timber yard between Karlstrasse (today’s Reinhardtstrasse) and Schiffbauerdamm along the Spree River (the two streets are connected today by Am Zirkus); unfortunately, it proved much too big for its purpose: A total fiasco, the marketplace closed in a matter of months.

The building was used as an arms depot during the war of 1870, until a real estate company took it over and transformed it into a circus, which they rented out to Albert Salamonsky (1839-1913). Salamonsky used it from 1873 to 1878 for seasons that ran from December to April, before eventually moving to Moscow—where he built a new circus on Tsvetnoy Boulevard. The Markthalle circus was subsequently rented out in 1879 to Ernst Renz who secured a six-year lease. Renz finally bought the building on March 25, 1886 for 1.33 million Marks (approximately US$ 5,590,000 today).

Before that, Renz had occupied the "Ottosche Circus" (since 1856), which became officially Circus Renz when he purchased it in 1863. But the circus was slated for demolition to allow the construction(French) A temporary circus building, originally made of wood and canvas, and later, of steel elements supporting a canvas top and wooden wall. Also known as a "semi-construction." of the Friedrichstrasse light rail station; Renz gave his last performance there on April 20, 1876 and announced the construction(French) A temporary circus building, originally made of wood and canvas, and later, of steel elements supporting a canvas top and wooden wall. Also known as a "semi-construction." of a new circus in Lindenstrasse, but the project never took shape. However, he had received a compensation of 2,460,000 Marks for his Friedrichtrasse circus, which was amply sufficient to finance the purchase of the Markhalle and its renovation in 1888/89 by an architect named Vogt, into the circus Ernst Renz wanted. It opened its doors on October 5, 1889.

Now, ten years later, Albert Schumann had succeeded his old mentor. With its impressive stables that could house 250 horses, the new Circus Albert Schumann was the perfect venue for Schumann to showcase his immensely creative equestrian acts—The Flower Horses, The Military Horses, The Brewery Horses, The Four Seasons, The Horse Going to Bed and many others that his brother Max, his nephews and his grandnephews will replicate and maintain with great talent for generations to come.

Albert Schumann’s Empire

Franz Renz died on July 7, 1901 at age sixty in Hamburg (where he still had a circus). In 1904, Albert Schumann bought the Markthalle circus from Renz’s heirs. As we have seen, Schumann had also inaugurated his new circus building in Vienna in April of the same year. He had already a wooden construction(French) A temporary circus building, originally made of wood and canvas, and later, of steel elements supporting a canvas top and wooden wall. Also known as a "semi-construction." in Frankfurt am Main that had done good business; in September, he began the construction(French) A temporary circus building, originally made of wood and canvas, and later, of steel elements supporting a canvas top and wooden wall. Also known as a "semi-construction." of a brick-and-mortar multi-purpose house to replace it, designed by the architects Friedrich Kristeller and Hugo Sonenthal. The new Schumann Circus-Theater could be used either as a circus or as a variety theater.

Located opposite the Hauptbahnhof (the main train station) on Banhofs Platz, at the center of the city, the building occupied the block between Karlstrasse and Taunusstrasse—two blocks west of Schumann’s previous location. The Schumann Circus-Theater opened its doors on December 5, 1905. Its huge, 3500-seat auditorium (in theater mode) was equipped with a stage, and the orchestra seats could be removed to give way to a traditional circus ring. The building hosted a short circus season every year, followed by series of variety shows and operettas.Albert Schumann gave the management of his new building to his brother-in-law, Julius Seeth, and later to Seeth’s brother-in-law, British-born equestrian Joe Hodgini (1865-1950). The Schumann Circus-Theater would remain a Frankfurt cultural landmark until WWII, and a major source of income for Albert Schumann after his retirement and until his death in 1939. Schumann didn’t live to see the building’s auditorium destroyed by the massive Allies’ bombing of March 1944. All what was left after that was its elaborate façade, and, right behind it, its foyer; they were finally demolished in 1960.

With circus buildings in Berlin, Vienna and Frankfurt, Albert Schumann had become a force to reckon with. Now that Franz Renz was out of the way, Schumann's only competition on the Western European "urban circus" scene was Paul Busch, who actually surpassed him. Albert Schumann’s strength was his amazing equestrian acts, for which he was still renowned—but with the advent of the twentieth century, the world was changing at a rapid pace, and so did audiences’ tastes. With his modern Berlin circus, which allowed him to produce elaborate, highly theatrical pantomimes, Paul Busch was quickly gaining the upper hand.

Albert Schumann took notice. In 1909, he had his Berlin circus refurbished with the addition of a gigantic 800 m2 stage (approximately 8,612 square feet), with a large proscenium adjoining the ring—an amenity comparable to, yet much bigger than, Circus Busch’s stage. This caught the attention of the famous theater director and producer Max Reinhardt (1873-1943): On November 12, 1910, he gave the first performance of his ground-breaking spectacular production of Sophocles’ Oedipus Rex at Circus Albert Schumann. Reinhardt used again the circus in October of 1911 for his production of Euripides’s Orestes, and in December of the same year for Hugo von Hofmannsthal’s Jedermann ("Anybody").

The Final Years

The Reinhardt experiences had been good business opportunities for Albert Schumann: His huge circus was expensive to run, and difficult to fill as a traditional circus, even with shows that were always of the highest quality: He had to fend off the increasingly strong competition of the very successful Paul Busch—who, thanks in part to his wife, Constance, and daughter Paula was probably better attuned to the audiences’ changing tastes than the more traditionalist Schumann. Nonetheless, in spite of all these difficulties, Circus Albert Schumann remained Berlin’s grand old circus, the true conservatory of German equestrian circus tradition.His Frankfurt circus-theater, of which the greater part of the season was devoted to varieties, was much more profitable, as was his circus in Vienna, whose season was also split between circus and varieties. In 1914, Albert Schumann was contemplating retirement and tried to sell his Berlin circus to Max Reinhardt: it had proved to have the right size to accommodate Reinhardt’s elaborate productions, and Reinhardt had done very good business there in 1910 and 1911. Reinhardt was indeed interested, but the advent of the First World War stalled the negotiations for some time.

In 1915, Albert Schumann finally retired from active circus life; his circuses, which were managed by competent collaborators, remained active. Then, in 1917, the creation of the Deutsches National-Theater with the financial backing of Max Reinhardt revived the negotiations between Schumann and the theater producer: On April 1, 1918, the Deutsches National-Theater company bought the building from Albert Schumamnn for 2.75 million marks (approximately US$ 10,165,000 today). Berlin’s Circus Albert Schumann gave its last circus performance on March 31, 1918. On November 11, the war was over.

Transformed into an ultra-modern theater in the new "expressionist" style by the architect Hans Poelzig (1869-1936), with a new façade shockingly painted raspberry red, the Deutsches National-Theater opened its doors November 28, 1919. In January 1920, Reinhardt resigned from its management and was replaced by the theater director and producer and Reinhardt's former collaborator Felix Holländer (1867-1931). Then the house had a checkered history, oscillating between variety and theater. It survived the bombings of WWII and became, in 1945, a variety theater—transformed again into a revue theater in 1980, the famous Friedrichstadt Palatz. It was finally demolished in 1985. (The Friedrichstadt Palatz, which still exist, was relocated nearby.)

As for Albert Schumann, he retired to the large house he had acquired in Neuenhagen bei Berlin, nineteen kilometers from the German capital—which is still extent and known today as the Schumann Villa. The sale of his circus in Berlin and the income generated by his other establishments, especially the Schumann Circus-Theater in Frankfurt, added to good financial investments, had made him a rich man indeed. He lived in good comfort until his death on August 15, 1939 at age eighty-one. He was laid to rest in the Dorotheenstädtischer Friedhof II cemetery in Berlin-Mitte, where his grave had been designated a landmark in 1984. Sadly, the Schumanns’ "German line" ended with him.

THE SCANDINAVIAN LINE: MAX SCHUMANN AND SONS

For all Albert Schumann’s accomplishments, the Schumann dynasty didn’t actually flourish in its native Germany: Thanks to Gotthold Schumann’s elder son, Max, it would become mostly known as a Scandinavian dynasty whose home base was in Denmark. Born in 1853, Max was five years older than Albert, but he left the family circus at the same time as his brother (1876) to pursue an independent career as an equestrian acrobat and trainer.

For several years, Max toured India (then the "crown jewel" of the British Empire) with the English circus Wilson. It is during this time that he met and married Victoria Cooke, who belonged to the old (and prolific) Scottish circus dynasty. Together they had three sons: Willy (1880-1936) and Ernst (1884-1960), both born in India, and Oscar (1886-1954), who was born in St. Patersburg, Russia, during an engagement at Circus Ciniselli, where Max had rejoined his father, Gotthold, who was performing there in the winter of 1886-1987.

When he returned to Germany in 1891 to succeed his aging father (who was sixty-seven) at the helm of Circus Schumann, Max had lost his German citizenship due to a too long sojourn abroad. Instead of having it restored, he bought a large property in the center of Stockholm and applied for Swedish citizenship. Max’s choice was probably motivated by the fact that, contrary to other European countries, Sweden had not known any military conflict since 1812, and tended to remain neutral: Thus, Max could avoid what had happened to his father in 1866, when all his horses had been requisitioned by the Prussian army.

Gotthold Schumann, the founder of the dynasty, died on December 23, 1908, at age eighty-four. The circus he had created was not a German entity anymore. Now in charge of the family circus, Max Schumann, the Swedish citizen, boosted its importance, and made it one of Scandinavia’s major circuses, traveling on a territory that included not only Sweden, Denmark and Norway, but also Germany, The Netherlands, Switzerland and Italy. Max's sons had, like him, acquired the Swedish nationality; they learned the language and made their mandatory military service in the Royal Cavalry in Stockholm.

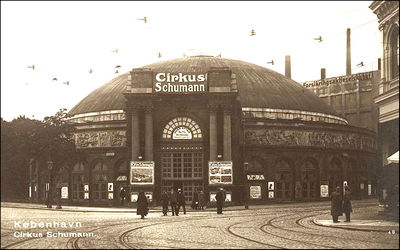

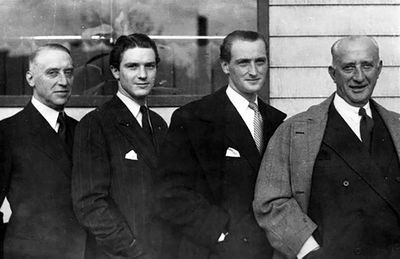

Willy, Ernst and Oscar Schumann: Cirkus Bröderna Schumann

When the First World War started in 1914, Max Schumann’s circus, which was touring in Switzerland, was forced to cancel his performances; now sixty-one, Max considered dissolving his company, but his sons refused and tried to resume their tour in Germany. Unfortunately, the war had created a horse fodder shortage in the country, and they eventually tried their luck in Denmark, which had remained neutral. In 1916, they secured a lease on Copenhagen’s Cirkusbygningen, the city’s circus building.The company reorganized under the name of Cirkus Broderna Schumann (Schumann Brothers Circus), a title it will keep until its closing in 1969. Thus, Copenhagen became the Schumann brothers’ base of operations. Willy Schumann, the oldest brother (born October 15, 1880) took charge of the administrative management while Ernst and Oscar were in charge of the performances, and of the training and presentation of their horses. Obviously, the brothers felt comfortable in Denmark: The country was not at war, circuses were welcome, and since they already spoke Swedish, Max and his sons had no trouble learning Danish, which is also a Scandinavian language.

In 1921, they expanded their activities to Göteborg and Stockholm in Sweden. In Göteborg, they rented the circus building of Lorensberg, in the city’s center, and in Stockholm, they took quarters at the Royal Circus building in the Djurgården. They also rented, from time to time, Oslo's Cirkus Verdensteater in Norway. There were many circus buildings in Europe at the time, and the Schumanns toured exclusively from one building to another. They had neither a big topThe circus tent. America: The main tent of a traveling circus, where the show is performed, as opposed to the other tops. (French, Russian: Chapiteau), nor transport wagons and caravans; they had only their horses and the equipment needed for their presentation, and they all traveled by rail.Since the Schumanns returned every year to the same places (Copenhagen, Stockholm and Göteborg) for long periods of time, they couldn’t present the same equestrian acts from one season to the next. In Copenhagen, where they stayed five months each year, their equestrian presentations changed every month, as well as the rest of the program (the artists were generally contracted for one month, like in most of Europe’s resident circuses). This tradition was respected until 1967. In this context, the great diversity of their uncle Albert Schumann’s equestrian presentations became a source for inspiration. Ernst and Oscar also developed a gentle training system free of pressure, which they will pass on to the following generations.

After their engagement in Göteborg, where they presented a selection of their equestrian presentations from the Copenhagen season, the family took its winter quarters in Odrupal, north of Copenhagen, before going in engagement with their equestrian acts in other European circuses for the winter season. From 1921 to 1938, they had regular engagements with the Bertram Mills Circus for its season at Kensington’s Olympia in London (where Willy Schumann acted as Equestrian Director for many years), and until the advent of WWII, they also performed at the circus of Riga in Latvia.

The War Years

Willy Schumann passed away on July 1, 1936 in Bad Nauheim (a famous German spa known for treating heart diseases) at age fifty-six. He and his wife, Helene, didn’t have children. His youngest brother Oscar succeeded him at the helm of the Cirkus Broderna Schumann company. Like Willy, Ernst (who was born on November 18, 1884 in Madras, India) and his first wife, Aase (1895-1946), didn’t have any children—although he remarried in 1947, after the death of Aase, with the actress Tove Boëtius (1919-1976), and had then two children, Eva and John Ernst (b.1948); the latter married Germaine Dedessus Le Moutier, of the Dior Sisters, but eventually left the circus.However, Oscar (born in St. Petersburg, Russia on October 7, 1886), who had married in 1912 Varvara (Vardya) Beketov (1885-1965), the sister of the Russian circus director Mathias Beletov, had three children: Cecilie (1913-1974), Albert (1915-2001) and Max (1916-2004). Oscar appointed his elder son, Albert, who was just twenty-one, to second him.

The junior Albert and Max already participated in the training of the horse acts (there were at times more than 100 horses in the stables), which they also presented along with their uncle Ernst, still in charge of horse purchase and training and of the performances. Ernst continued to appear in the ring until the early fifties, before eventually retiring in 1952. Of the three brothers, he was the most elegant and charismatic; when in the ring conducting his liberty"Liberty act", "Horses at liberty": Unmounted horses presented from the center of the ring by an equestrian directing his charges with his voice, body movements, and signals from a ''chambrière'' (French), or long whip. acts, he always presented himself impeccably, in tails and white tie and wearing his signature monocle. He was a classy performer, a trait he passed on to his nephews.

In 1937, Cirkus Schumann toured in Sweden under canvas in association with Carl Strassburger. The following year, the owners of Copenhagen’s circus building increased its rent; after fruitless negotiations, the Schumanns left the Cirkusbygningen, and the building was rented out for short seasons to other circus companies (Miehe, Jean Houcke, Mikkenie-Strassburger…). The Schumanns kept their seasons in Stockholm and Göteborg, and toured Denmark in the summer under Cirkus Belli’s big topThe circus tent. America: The main tent of a traveling circus, where the show is performed, as opposed to the other tops. (French, Russian: Chapiteau). They spent the winter in the old Circus Renz in Vienna, owned by Heinrich and Lorenz Hagenbeck, and then went to Göteborg and Stockholm. Their 1939 summer tour in Sweden was interrupted abruptly by the beginning of WWII in Europe: Sweden closed its borders, and all circus tours were cancelled on account of fuel rationing.

In 1940, the Schumanns performed as usual in Göteborg and Stockholm, and then went on tour in Denmark with Circus Belli's equipment. The following year, after Göteborg and Stockholm and a Danish tour with Belli, they went to perform in the the former Circus Blumenfeld building in Magdeburg in October, Circus Sarrasani in Dresden in November and in the Hagenbecks' building in Vienna in December and January. In 1942, they were at Munich's Kronebau in February, after which they spent the season with Circus Medrano-Swoboda in Austria. In November, they performed with Jakob Busch in the Magdeburg building.

Finally, in 1943, they were able to return to the Cirkusbygningen in Copenhagen, which had run out of short-term tenants; it was going to be their home for twenty-five consecutive summer seasons (Copenhagen’s regulations forbade the presentation of circus shows in the building during the winter)—until the closing of Cirkus Broderna Schumann in 1969.

Cecilie, Albert and Max Schumann

The war over, the Schumanns resumed their old performance schedule in Stockholm, Copenhagen and Göteborg. From 1947 to 1955, they also spent their winter with the huge circus show Tom Arnold presented each year (from 1947 to 1957) for the holiday season at the Harringay arena in London. Just before their last season at Harringay, on September 6, 1954, Oscar Schumann passed away in Frederiksberg, Copenhagen, at age sixty-eight; Ernst, who was seventy, had retired from all his circus activities two years earlier and the fourth generation took over—Albert in charge of the administrative management and Max taking care of the performances. (Ernst will pass away on May 29, 1960 in his home in Roskilde, near Copenhagen.)Cecilie (Cissie), Albert and Max had been trained by their father in all equestrian disciplines. They began to appear in the ring at an early age, and as soon as they reached adulthood, Albert and Max were sent to other circuses all over Europe with Cirkus Schumann liberty"Liberty act", "Horses at liberty": Unmounted horses presented from the center of the ring by an equestrian directing his charges with his voice, body movements, and signals from a ''chambrière'' (French), or long whip. or high-schoolA display of equestrian dressage by a rider mounting a horse and leading it into classic moves and steps. (From the French: Haute école) acts until the beginning of WWII. When they took over, they were experienced trainer and performers, and Albert was already well acquainted with all aspects of the family circus’s management—which was quite an unusual affair, since the Schumanns ran the last circus performing exclusively in buildings, with no big topThe circus tent. America: The main tent of a traveling circus, where the show is performed, as opposed to the other tops. (French, Russian: Chapiteau) or traveling equipment.

Besides being equally talented high-schoolA display of equestrian dressage by a rider mounting a horse and leading it into classic moves and steps. (From the French: Haute école) riders, Albert and Max had their own specialties when it came to liberty"Liberty act", "Horses at liberty": Unmounted horses presented from the center of the ring by an equestrian directing his charges with his voice, body movements, and signals from a ''chambrière'' (French), or long whip. acts: Albert preferred large groups of 12, 18 or 24 horses, whereas Max liked smaller groups with ponies or Norwegian horses, and special presentations such as “Maxi-Mini” (large horse and Shetland pony working together), the horse going to bed by himself, the "pony kindergarten" with ponies playing on seesaws, carousels, etc., or acts created by their granduncle Albert, such as The Gates, in which a horse chased a clown through a series of gates. They could nonetheless replace one another at any time when necessary: One brother just had to observe the other’s act a couple of times to take it over, so good was their shared training technique. In the ring, Max was the most charismatic.Cecilie, their sister, had married the English bareback rider Johnny Kayes in 1938, and resettled in Britain, where her husband went on to manage the Kayes Brothers Circus with his brother Jimmy from 1948 to 1957, before presenting chimpanzee, dog, and horse acts with other circuses until the 1970s. Albert and Max were both married in 1946: Max with Vivi Mikkelsen (1926-2009), the daughter of a Copenhagen veterinarian, and Albert with Paulina Andreu i Busto (1921-2020), the daughter of the famous clown Charlie Rivel—a major circus star, notably in Germany and Scandinavia.

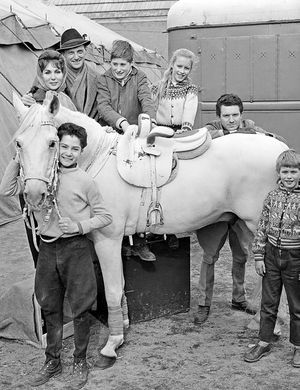

The arrival of Paulina in the family had a strong impact on the Schumanns’ equestrian presentations. Paulina, who was stunningly beautiful and had a great charisma in the ring, was an imaginative and versatile artist; she had acquired her sense of spectacle on the variety stage, where she supplemented her celebrated father’s clown and trapeze acts with a dancing act she performed with her brothers and her own tight wireA tight, light metallic cable, placed between two platforms not very far from the ground, on which a wire dancer perform dance steps, and acrobatic exercises such as somersaults. (Also: Low Wire) act. Within a few years, Paulina Schumann reached a genuine star status in Denmark and Sweden, often appearing on magazine covers: She became Circus Schumann’s iconic superstar.

The Schumanns’ Golden Age

After the birth of her two sons, Benny (born May 23, 1945) and Jacques (b. 1947), Oscar Schumann, her father-in-law, asked Paulina to present a liberty"Liberty act", "Horses at liberty": Unmounted horses presented from the center of the ring by an equestrian directing his charges with his voice, body movements, and signals from a ''chambrière'' (French), or long whip. act with six horses, even though she had no equestrian experience. The feisty Paulina answered: "I will do it, but I will do it my way." Soon, under Paulina’s supervision, high-schoolA display of equestrian dressage by a rider mounting a horse and leading it into classic moves and steps. (From the French: Haute école) and liberty"Liberty act", "Horses at liberty": Unmounted horses presented from the center of the ring by an equestrian directing his charges with his voice, body movements, and signals from a ''chambrière'' (French), or long whip. acts became full-fledged productions developed around a theme, with appropriate costumes created by the likes of the legendary Maison Vicaire in Paris after Paulina’s specifications, and special musical arrangements and lighting.Whereas the frugal Oscar had been content with a traditional evening suit for the presentation of his liberty"Liberty act", "Horses at liberty": Unmounted horses presented from the center of the ring by an equestrian directing his charges with his voice, body movements, and signals from a ''chambrière'' (French), or long whip. acts and an English-style wardrobe for high-schoolA display of equestrian dressage by a rider mounting a horse and leading it into classic moves and steps. (From the French: Haute école) acts, his children and grandchildren (Benny, Jacques, and Max’s two children, Katja, born in 1949, and Philip, born in 1953) appeared in the ring in a wide variety of elegant and sometimes colorful costumes, differing for each specific presentation. It represented perhaps, in Oscar’s view, extravagant expenses, but it actually defined the most glorious period of the Scandinavian Schumanns’ saga.

Paulina had been encouraged in her "extravagance" by Harringay’s producer Tom Arnold, and more precisely the show’s director, Clement Buston. They both erred on the spectacular side, and impressed by Paulina's ideas and her sense of showmanship, they agreed to invest in her expensive costumes and staging concepts for Harringay’s winter shows. It was originally the results of this financial collaboration that could be seen each year in the fully produced, brilliantly themed equestrian acts the Schumanns presented in the circuses of Stockholm, Copenhagen, Göteborg and, of course, at Harringay.

Starting in the winter of 1957-58, the Schumanns returned to London, this time for the prestigious Bertram Mills Circus’ holiday season at Kensington’s Olympia, where the family had performed regularly before WWII. They appeared with Mills until Cyril and Bernard Mills closed their circus in 1967. The Schumanns' acts now included Albert and Paulina; their sons Benny and Jacques; Max and his daughter Katja; and sometimes the addition of Douglas Kossmeyer or Johnny Kayes. Paulina also created a new tight wireA tight, light metallic cable, placed between two platforms not very far from the ground, on which a wire dancer perform dance steps, and acrobatic exercises such as somersaults. (Also: Low Wire) act in which she included her son Benny.

During this period, most of the Schumanns’ equestrian acts were inspired, musically as well as visually, by the great movie blockbusters of the era. Always presenting both high-schoolA display of equestrian dressage by a rider mounting a horse and leading it into classic moves and steps. (From the French: Haute école) and liberty"Liberty act", "Horses at liberty": Unmounted horses presented from the center of the ring by an equestrian directing his charges with his voice, body movements, and signals from a ''chambrière'' (French), or long whip. acts in each program, the Schumanns staged superb equestrian impressions of Doctor Zhivago, My Fair Lady, Robin Hood, Gigi—as well as The Schumanns in Mexico (1963), Feria de Primavera (1964), and From The Good Old Days: Paris 1900 (1965). In the sixties, it had become a tradition for Copenhagen’s summer visitors, whether European or American, to visit Circus Schumann: It was indeed one of Europe’s most prestigious circuses, and for horse enthusiasts, incontestably the world’s premier circus for equestrian arts.

Yet, this golden age was coming to an end. In 1957, Stockholm’s circus at the Djugården changed owners and was rented out to Sveriges Television, which used it to record its live audience shows. The Schumanns maintained their Stockholm season under a big topThe circus tent. America: The main tent of a traveling circus, where the show is performed, as opposed to the other tops. (French, Russian: Chapiteau), but a steady loss of audience constrained them to abandon it in 1966. Meanwhile, the Cirkusbygningen in Copenhagen had been bought by a supermarket chain, which intended to replace the circus with a new supermarket. However, such an enterprise revealed to be much too expensive, and to recoup their investment, they began to raise regularly the building’s rental fees.The final blow came in 1969, when the Schumanns lost their winter season after the Bertram Mills Circus, which had already folded its touring tents, gave its last performance at London’s Olympia in January 1967. Without their lucrative winter season, the combined profits of Copenhagen and Göteborg were not sufficient to offset their loss of income, especially considering the ever-increasing rent of the Copenhagen building. Albert Schumann, who was in charge of the circus finances was facing a dire situation; to make matters worse, his marriage was on the rocks. In 1968, he got the opportunity to sell twenty Arab stallions to the French circus Sabine Rancy; he jumped on the occasion, and then looked for other buyers for the remaining of the horses.

The 1969 season was the very last for the Cirkus Broderna Schumann. Albert and Paulina, now separated, didn’t participate in the shows in Copenhagen and Göteborg, and Max and his daughter Katja presented the equestrian acts with horses rented from Circus Krone. When the season was over, the circus of Göteborg, which had been in a serious state of disrepair for some time, was demolished. As for the Copenhagen’s building, its rent had become so prohibitive that Albert decided not to renew his bail for 1970. Thus, the prestigious Cirkus Broderna Schumann sadly ceased to exist at the end of 1969. Like Cyril and Bernard Mills before him, Albert and Max Schumann took this decision when it was still time, to avoid the prospect of a bankruptcy.

The Aftermath

Albert retired and went on to live in Cubelles, near Barcelona, Spain, in a villa close to his father-in-law's home, and then moved in 1982 to Marabella, on the Costa del Sol. He returned to Barcelona in 1998, where he passed away on August 27, 2001 after a long illness. He was eighty-six. Paulina had settled in Cubelles, near Barcelona, in her father’s home, and she became Charlie Rivel's partner, working with him notably at Munich’s Kronebau, and at Gröna Lunds, Stockholm’s amusement park, and appearing with him at the first International Circus Festival of Monte Carlo in 1974, where he received a Gold Clown. Paulina remained in Barcelona after her father’s death and was distinguished by the Spanish and Catalan governments as a major circus personality. She passed away on October 16, 2020, four months shy of her 100th birthday.

Benny, their son, had already embraced a juggling career in 1967 with a spinning-plate act that took him, among other places, to Las Vegas. In the 1980s, he began also to work as a clownGeneric term for all clowns and augustes. '''Specific:''' In Europe, the elegant, whiteface character who plays the role of the straight man to the Auguste in a clown team., including in his act his spinning plates and his wire-walking skills. He eventually put together a one-man show with which he performed for special events—which he still does to this day (as of 2021). In 2001, he bought some ponies that he trained in the Schumann tradition, and he also got a high-schoolA display of equestrian dressage by a rider mounting a horse and leading it into classic moves and steps. (From the French: Haute école) horse. In 2017, he celebrated his fifty years in the ring and on stage at the Cirkusbygningen in Copenhagen, which is today a dinner-show called Wallmans Dinnerparty.Max, too, didn’t call it quits. He opened a dressage school in the Schumanns’ old winter quarters in Odrupal, while his daughter Katja began a brilliant career as a high-schoolA display of equestrian dressage by a rider mounting a horse and leading it into classic moves and steps. (From the French: Haute école) rider in other European circuses, appearing also in the first International Circus Festival of Monte Carlo, where she was awarded the coveted Dame du Cirque award. Max, who was there, offered champagne to the entire cast! Three years later, Katja Schumann won the Circus World Championships competition in London.

That same year, 1977, Max decided to hit the road again under a big topThe circus tent. America: The main tent of a traveling circus, where the show is performed, as opposed to the other tops. (French, Russian: Chapiteau), and Cirkus Max Schumann began touring Denmark in the summer months. Katja presented a liberty"Liberty act", "Horses at liberty": Unmounted horses presented from the center of the ring by an equestrian directing his charges with his voice, body movements, and signals from a ''chambrière'' (French), or long whip. act and her high-schoolA display of equestrian dressage by a rider mounting a horse and leading it into classic moves and steps. (From the French: Haute école) act, and Max a "Maxi-Mini" act. Katja's brother Philip came on board as technical director and appeared at times in a triple high-schoolA display of equestrian dressage by a rider mounting a horse and leading it into classic moves and steps. (From the French: Haute école) act with his father and his sister. Yet, as it had shown in the 1960s in Sweden, it is possible that, in the Scandinavian audiences’ psyche, the name Schumann had become difficult to associate with the idea of a tenting circus. The audience never built enough to keep the enterprise afloat and, in 1982, Circus Max Schumann folded its tents.

Katja went to work in the United States with the Big Apple Circus, whose director, Paul Binder, she married in 1985. Together they had two children, Katherine Rose (b.1985) and Max Abraham (b.1987). Max, who had no intention to retire, went on to present horses and ponies for other circuses such as Arena and Dannebrog. Then, in 1993, Max joined his daughter at the Big Apple Circus, accompanied by Vivi. He returned to Denmark in 2002 and finally retired in Lundum in Central Jutland. He passed away on December 28, 2004 and was laid to rest in the Lundum Cemetery. His wife Vivi died on November 9, 2009.

Katja Schumann and Paul Binder separated in 2004, and Katja returned to Scandinavia to work with Robert Bronett (of the Swedish Circus Scott) in his equestrian show, Levade. She worked subsequently with Circus Mascot and Circus Dannebrog and other organizations in Denmark and Sweden. In 2015, she purchased and renovated a dilapidated farm in the tourist town of Løkken-Vrå, in Denmark's northern Jutland, and transformed it into a working animal farm, seasonal mini-circus, and a museum showcasing Schumann family's memorabilia.

In the summer of 2015, Katja and Benny Schumann reunited for an equestrian spectacle titled The Medicine Man on Fyn Island in Denmark. Katja’s niece Laura (Philip’s daughter), who had performed with her at the Big Apple Circus, participated in the show with her American husband, Luis, an acrobat and stuntman. Katja and Benny still work together from time to time for special events or present mini circus shows focusing on horses. Laura Schumann, who represents the Schumanns’ sixth generation, gives equestrian performances, often with Benny and Katja, and is intent on preserving the great Schumann equestrian tradition.

Suggested Reading

- Alf Danielsson, Cirkusliv (Malmö, Askild & Kärnekul, 1974) — ISBN 91-7008-199-9

- Anders Enevig, Cirkus i Danmark, 3 vol. (Lyngby, Dansk Historisk Håndbogsforlag ApS, 1982) — ISBN 87-85207-61-6

- Per Arne Wåhlberg, Cirkus i Sverige (Stockholm, Carlssons Bokförlag, 1992) — ISBN 91-7798-591-5

See Also

- Video: Paulina, Albert, Max, Katja, Benny & Jacques Schumann, high school act, at Cirkus Schumann in Copenhagen (1964)

- Video: Albert Schumann, liberty act, at Cirkus Schumann in Copenhagen (c.1965)

- Video: Paulina Schumann, acts medley, at Cirkus Schumann, Copenhagen (c.1955-1965)

- Video: Albert Schumann, Rhapsody In Blue, liberty"Liberty act", "Horses at liberty": Unmounted horses presented from the center of the ring by an equestrian directing his charges with his voice, body movements, and signals from a ''chambrière'' (French), or long whip. act, at Cirkus Schumann, Copenhagen (1965)

- Video: Paulina Schumann, high school act at Cirkus Schumann, Copenhagen (1965)

- Video: Paulina, Albert, Max, Katja, Benny & Jacques Schumann, high school act, at Cirkus Schumann in Copenhagen (1965)

- Video: Albert Schumann, 18-horse liberty act, at Cirkus Schumann in Copenhagen (1967)

- Biographies: Paulina Schumann, Katja Schumann

- History: Cirkusbygningen (Copenhagen), Circus Schumann (Frankfurt)