The Great Carmo

From Circopedia

Juggler, Magician, Circus Owner

By Don Stacey

Relatively little has been written of Harry Cameron (1881-1944), better known as "The Great Carmo," apart from a small volume entitled The Great Carmo, The Colossus of Mystery, by magician and writer Val Andrews in 2001. Yet, Carmo was at one time one of the leading illusionists of the British variety theatre scene, and for a short period, the owner of a circus stalked by tragedy. He might also be considered the man who launched the Bertram Mills Circus on its first tour, having had a short connection with Bertram W. Mills and his two sons in 1929, prior to the appearance of the full-fledged Mills tenting show in 1930.

Australian Beginnings

Although of Scottish origins (his parents had emigrated to Australia in about 1880), Harry Cameron was born in Brunswick, a suburb of Melbourne, Australia on November 8, 1881. His father was an engineer; unbeknownst to him, Harry was destined to become a magician and illusionist who would rival the "greats" of his era: Lafayette, Chung Ling Soo, Lyle, Dante, Murray, Chefalo, and Kalanag, whose huge stage presentations were among the finest in theatrical history.

As a youngster, and without any encouragement from his family, Harry developed a love for show business. He had been first entranced by the magic quality of a travelling circus he had visited, and then by Paul Cinquevalli, the greatest juggler of his time, whom he saw in a variety theatre in Melbourne: Harry set out to emulate the feats of his new idol in his juggling, balance and strongman routines.

Hence Harry started practising juggling, and whenever possible, without his parents’ knowledge, he frequented theatres and travelling shows. Leaving school at fourteen, he was first apprenticed to a grocer and developed his muscles carrying sacks of flour up to a ladder. Next, he worked in a brass foundry and, in his spare time, took part in a Minstrel show, where he began learning the business of entertainment and formed his flair for showmanship and his stage-sense.

When his father found out about Harry’s clandestine affair with show business, he gave him an ultimatum: Either to abandon his artistic ambitions, or to leave home. Harry chose the second option and went on to travelling with the Minstrel show for a year, and later with Rowley’s Waxworks and Varieties—where he performed his budding juggling and strongman act. He then continued to develop it in other shows.

Next, Harry moved on to Ashton’s Circus, playing in the bush townships of Australia, a hard grounding in the circus life. There, attempting to learn wire walking, he had a fall followed by a penniless period in hospital, which led to reconciliation with his parents. Eventually, Harry developed a successful variety career with an act that combined juggling, feats of strength, quick-changes, and impressions. He married his singer-assistant, Nellie Lloyd, in Sydney, on January 5, 1903.

Enter The Carmos

In Victor Martyn, another Melbourne boy, Harry found a friend who also ran away to join a circus. Victor was keenly interested in magic, and while Harry taught him juggling, Victor taught Harry magic tricks. (The Martyn family eventually acquired a strong reputation in the world of juggling; Victor’s son, Topper Martyn, became a great comedy magician and juggler.) Then the Carmos, as Harry and Nellie’s act had become known, met up with a brilliant magician, Servais Le Roy (1865-1953), of the celebrated act of Le Roy, Talma & Bosco, when LeRoy travelled to Australia in 1905-1906. Harry’s lasting friendship with the man would greatly influence his later career as an illusionist.The Carmos joined a variety show, Heller’s Entertainers, run by "Professor" George Heller and his wife, Maude, with which they travelled to England early in 1907. Their ship, the White Star liner Suevic, sailed on the 2nd of February from Sydney and foundered on the rocks off the Lizard Point in Cornwall. Everyone was safe, but the Carmos lost their cabin luggage; fortunately, their props stored in the hold were later recovered.

When the Hellers returned to Australia, Harry and Nellie chose to settle in England, where they played the British music halls, and also toured in the United States and in France. Harry began adding magic effects to his routine; The Devil’s Cage, made by Servais Le Roy for him in London, was one of his most arresting features. At the end of 1911, Le Roy loaned to Harry one of his best magicians, Max Sterling, to help him produce a true magic show, and Carmo’s new act was launched as Carmo, The Master Phantasist. Harry’s combination of sensational and novel illusions, equilibristics, juggling and acrobatic feats, spectacular tableaux and other features led to his being described in the theatrical press as "one of the most accomplished artistes in variety."

The marriage of Harry and Nellie floundered, however, and although she remained in the act, they separated in July of 1911, and divorced on the 30th of June 1913. In the meantime, Harry had met Rose Alice Pemberton, who was professionally known as Alma May and who had a three-year-old illegitimate son. At the time they met, she was touring with Fred Karno’s famous show, Mumming Birds, which spawned an immensely talented young comedian named Charles Chaplin. Just a month after his divorce came through, Harry Carmo married Alma May.

Harry’s second marriage proved to be a very successful one, for not only was Alma a beautiful woman with whom he remained in love to the end, but she was also an astute businesswoman with valuable stage experience, a blessing for Harry who, although a fine showman, never had any money or business sense.

The Great Carmo

Harry and Alma went to Australia in late 1913 to work for the Le Roy, Talma & Bosco show—and by some coincidence, sailed on the rebuilt White Star ship, Suevic. On the outbreak of the Great War in August 1914, they all decided to set sail for the United States, where they opened in San Francisco, the first stop of a tour booked by Servais Le Roy. When the tour ended in Pennsylvania, Le Roy rented a small empty theatre, where he assisted Carmo in building his first magic spectacular.

After a few months, "The Great Carmo"—as he was henceforth to be known—and his girl-assistants were ready to return to England, and they tried to book passages on the Cunard liner Lusitania, which was sailing from New York on May 1, 1915. Although cabin accommodations were available, there was no space in the hold for Carmo’s huge amount of stage and magic props, and he had to wait for a later ship. It was a lucky strike: This was to be Lusitania’s last voyage; she was torpedoed by a German U-Boat off the coast of Ireland on May 7, an event that led the United States to declare war on Germany.The show Carmo eventually developed in England was truly impressive, with a variety of animals participating in the illusions—including a Bengal tiger, an elephant, a leopard, horses, snakes, and a lion that was featured in The Lion’s Bride illusion, which had been part of Le Roy’s repertoire, and in that of another famous illusionist, The Great Lafayette. Carmo’s version elaborated the original idea to become Thrown To The Lions or The Lion’s Prey, and was considered one of the greatest magic tricks of its time—a richly costumed and staged silent drama replete with music and lighting effects.

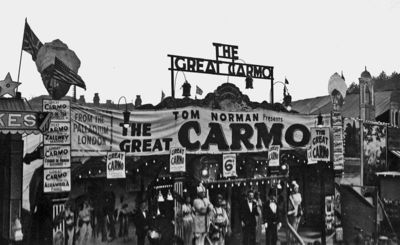

With a growing collection of animals, Carmo’s troupe rapidly expanded to around forty performers, playing all the leading variety theatres in the British Isles and, once the war over, going on continental tours, where the show was a great sensation—particularly in Spain and Portugal. They also played a four-week engagement in Paris, and London’s famous Palladium Theatre. The show grew ever more opulent and splendid, with more performers, more animals, and more elaborate illusions—with Carmo buying some of the most sensational illusions of the great magician, David Devant. The Great Carmo’s show eventually became the most vaunted magic show of its era in England.

Farewell Alma: Enter Rita

In 1926, as his fortunes mounted, Carmo bought a big farmhouse in Shirley, Surrey, with enough buildings and grounds to house all the animals, vehicles, and properties the big show needed. It was to be known as Carmo Manor. But tragedy struck in September of the following year, when Alma died of cancer at their home while Harry was on tour with his show in Scotland. Carmo couldn’t even leave the show to attend her funeral. Alma’s death was a huge blow to him: Not only had she been the love of his life, she had also been his all-important business partner.

Yet, Harry would not remain alone. Back to right after the Great War, when Carmo’s show was playing the Willesden Hippodrome in Harlesden, London, eleven-year-old Rita Rogers, the daughter of a solicitor, saw his performance and was deeply impressed by Carmo’s onstage personality and charisma. The girl idolised the concept of his productions, and wove little romances from her memories of Harry Carmo. She wanted to go into show business and although her family had fallen into hard times, a family friend made it possible for her to train as a ballet dancer.

In 1923, at the age of sixteen, Rita appeared in a pantomimeA circus play, not necessarily mute, with a dramatic story-line (a regular feature in 18th and 19th century circus performances).; then she answered an advertisement for work as a dancer in a magic show. She found herself auditioning for a lady in a homely drawing room at an address in Camberwell, London, and was offered the job on the spot. She learnt later that the lady auditioning her was Carmo’s wife, Alma, and that she had been engaged with The Great Carmo’s Magical Moments production.

Rita quickly graduated from walking on in glamorous outfits to dancing and then to taking part in the magical playlets the great illusionist produced. It proved to be Rita’s destiny to be part of Harry Carmo’s world; ultimately, she would accompany him through the last stage of his life.

The Great Carmo Circus

After Alma’s death, Harry’s heart was no longer in the theatre business, and his thoughts returned to the world of circus and a long-held desire to stage his own circus, in which Alma had shown no interest whatsoever. By 1927, Carmo set about realising his old dream and began to assemble a travelling circus with the Barry family in Ireland; he purchased horses and lions, and commissioned Harry Bate, a well known magical supplier, to build for him a number of sideshow illusions.

Carmo displayed these static illusions for the 1927-1928 winter season at the Fun Fair Bertram W. Mills staged in the big hall at the Olympia of Kensington in London, and which was adjacent to his circus. The Mills programme also featured for the first time an act from the newly formed Carmo’s Circus, Baby June, the cycling elephant, claimed to be the youngest and smallest performing elephant in the world. (The elephant, which rode a heavy-built tricycle, later became known as Baby Carmo.)

Carmo’s lions were at first shown by a trainer named Frederick Guise, but he was soon dismissed for drinking, and Carmo acquired the services of Togare (Georg Kulovits) at the suggestion of Bertram Mills. Togare came from Circus Krone in Germany, and was a remarkable showman in the ring, a fine and courageous performer with good looks and an outstanding physique; he was on his way to becoming one of the most celebrated animal trainers of his era.

Frederick Martin, a publicity specialist and a circus fan, had recommended that Carmo use Lady Eleanor Smith, another fan and the daughter of Lord Birkenhead, to write the publicity material for the show. It was she whose publicity genius turned Togare into a matinee idol and christened him "The Valentino of the Ring"—for his stage resemblance with the late movie star and pop icon, who was still, two years after his death, an extraordinary box-office draw. (Eleanor Smith became closely involved with the Carmo and Mills circuses, and wrote a novel on circus life, Red Wagon [1930], which was made into a film starring Charles Bickford, Anthony Bushell and Greta Nissen in 1933.)

For his 1928-1929 season at Olympia, Bertram Mills featured two acts of the Great Carmo Circus, Togare with his lions, and "Captain" Ankner with the horses Carmo had purchased from Mills. Both the Carmo horses and Togare’s lions were announced as appearing for the first time in England, and Carmo’s Gallery of Illusions and his Australian Menagerie were also featured in the Fun Fair next to the circus.

The first Great Carmo Circus tour in Ireland proved a success, both artistically and financially, and at the same time, Harry continued his variety tours with his big magic show. Although Val Andrews, in his biography of Carmo, suggests that the Irish venture was only "a modest success," Harry planned a bigger and better show for his 1929 season—a show whose size and quality could make it become Britain’s biggest, tour the rest of the United Kingdom, and thus rival the largest circus of the British Isles, that of Lord George Sanger. Or so he thought.

The Carmo-Mills Experiment

Frederick Martin, who was a friend of both Carmo and Mills, brought the news to Carmo that Bertram Mills and his sons, Cyril and Bernard, were planning to launch a tenting show too, following on the success of their annual circus at Olympia in London since 1920. Bertram’s sons had followed their father into the business, but by now, there was not enough to occupy the three of them with a six-week winter season—and with a lack of top-class circuses touring the country, Mills saw a chance of capitalising, and occupying his two talented sons with running the travelling enterprise he planned.

However, it was somewhat doubtful at that time that two new big tenting shows competing against each other could survive, so a partnership deal was suggested—one that would eventually work to the advantage of the Mills family, enabling Cyril and Bernard Mills to explore the workings of a travelling show for the first time. In the event, they probably learnt more that year of how not to run a show than how to run one successfully.The Mills family had been persuaded to delay their own launch not only by their ignorance of tenting procedures, but also because Carmo had already a good programme fully booked. Their mutual contract therefore gave the full responsibility for that part of the deal to Carmo. (However, in his book, Bertram Mills Circus, Its Story, Cyril Mills remarked that "the programme we had when we were alone in 1930 was much better.")

The arrangement between Carmo and Mills was a strange one. While planning for their own show, Cyril Mills had been to Germany to study transportation, seating, tents, etc. on the best shows there—such as Krone, Sarrasani, and Busch, which were Europe’s (and perhaps the world’s) most technically advanced, comfortable, and efficient travelling circuses. In an air of secrecy, Cyril had ordered a tent from the reputable German tentmaker Stromeyer in Konstanz, and acquired second-hand seating for the poster printer Friedländer in Hamburg, who had taken it for a trade when the old Blumenfeld circus family went into financial hardship.

The seating included luxurious plush covered chairs for the boxes or front seats, but when Mills received it, only the three first rows of the bench seating had any backrests. By the time the show opened, apparently every bench had been provided with a backrest—something which was then unheard of in any British tenting circus. The big topThe circus tent. America: The main tent of a traveling circus, where the show is performed, as opposed to the other tops. (French, Russian: Chapiteau) had also two sets of king poles (main masts) and stakes, so that one set could be erected before the arrival of the show in a new town while it was still playing in another, and thus save precious time in the set-up.

Therefore all the tenting and seating equipment belonged to the Mills organisation, which also provided the administrative and general staff—apart from the grooms, who were part of Carmo’s programme package. Mills also provided the box office and office wagons, since they had to take care of the administrative staff. On his end, Carmo produced the programme, paid all the artistes, and provided the transport on which the show moved by road. Carmo’s second-hand vehicles, however, were certainly not the best—as Cyril Mills remembered: "I think Carmo’s transport averaged about three breakdowns per journey. It was so unreliable that we never planned to open before the evening performance on a Monday." (The show moved on Sundays, since Sunday performances—whether at the theatre, at the circus or anywhere else—were not permitted then in the United Kingdom.)

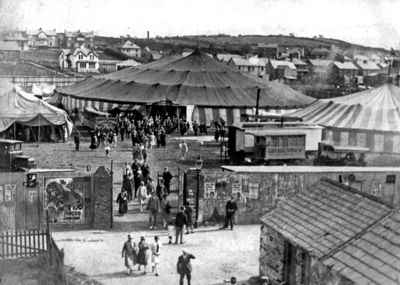

After many initial setbacks, the combined show finally opened in May 1929 at Gatford, London, but with solely the Great Carmo Circus and Menagerie title—in case the name of Mills should be sullied. Many voted it a wonderful show, however, and the biggest circus seen in the provinces since the palmy days of Lord George Sanger.It had a particularly strong program for that era, with not only Togare and Carmo’s lions, Emmerich Ankner with four groups of horses, and the cycling elephant Baby Carmo, but also attractions like the British rider Mona Connor; the Belgian clowns, The Bentos; Ruth Owens’s jumping horse, "Courage"; The Hansens’ perch pole act; the four Bonellys from Australia with a looping-the-loop aerial act; The Nonsens aerial ladder act; The Costellos’ hand balancing act; The 5 Balaguers, acrobatic jugglers; Los Gabriels, hat jugglers in clown costumes; a group of dancers plus a "skating ballet on real ice"; and the great acrobats on horseback, The Carolis—who would later figure many times with Bertram Mills Circus.

Carmo’s menagerie was claimed to contain "a host of rarities gathered from all parts of the world"—although Cyril Mills, maybe with a declining memory, felt sure much later that the menagerie contained only Togare’s lions, the Carmo’s horses and ponies, and the cycling elephant, Baby Carmo. The carpet clowns were not mentioned in the printed programme, but one of the many books by or on Lady Eleanor Smith mentions her meeting up at Carmo’s with clowns friends, including Whimsical Walker, Joe Craston and Joe Bert.

The show faced many technical and organisational setbacks during the tour, due to the lack of experience of its owners. But the Mills brothers were certainly learning fast, as their subsequent venture with the tenting Bertram Mills Circus would prove just a year later. Nonetheless, the show was very well received by both the press and the public; "everyone said it marked the beginning of a new era in the history of British circuses," recalled Cyril Mills.

The Great Carmo Circus travelled from May until the middle of November; Cyril Mills explained to this writer, "We kept the Mills-Carmo show going for more than an extra month after the contract was due to end just to please Carmo, because he was still not ready to re-open with his own equipment." Cyril Mills had doubts that Carmo could have gone through a winter season with his own tent, which he didn’t get from a reputable manufacturer, and whose delivery had been already postponed several times, but Harry Carmo couldn’t afford to lay off for five months.

The End Of The Great Carmo Circus

The Mills family and Harry Carmo parted company amicably on a Saturday night in Oxford, and Carmo planned to reopen at Wembley on Monday. "But," Cyril Mills recalled, "after a three-day struggle to get the new-type tent up [it was a then-innovative tent supported by four poles in square], he telephoned and from the sound of his voice, I suspected he was on the verge of tears. Could we lend him our tentmasterThe person in charge of setting up and putting down a circus tent. (See also: Boss Canvasman)? Of course, we could […]. The tentmasterThe person in charge of setting up and putting down a circus tent. (See also: Boss Canvasman) was rushed to Wembley, and within two days, tent and seating had been built up and the circus was able to open."

To any showman, tenting through a British winter was considered madness and fraught with difficulties. Carmo had paid £800, a large sum at that time, for a German heating apparatus to fill the tent with hot air. This had never been attempted before and was deemed a folly by the industry—always resistant to innovation brought in by outsiders. The winter season began on January 6, 1930, at the Harringay Greyhound Track in North London, and initially had some success. But the weather was unusually bad and the public jibbed at traipsing through thick mud to the heated tent. The show struggled on, often with empty houses, before reaching Birmingham in March 1930.

Although he was losing a lot of money, Carmo continued to pay his staff and artistes on full salary. But the weather deteriorated further and on the night of March 14, a heavy snowfall brought down his supposedly super-strong and especially low-pitched big topThe circus tent. America: The main tent of a traveling circus, where the show is performed, as opposed to the other tops. (French, Russian: Chapiteau). The canvas in shreds and the seating wrecked, it was the first of a series of disasters that befell the Great Carmo that winter. Ever the optimist, Carmo purchased—at great expense—a new big topThe circus tent. America: The main tent of a traveling circus, where the show is performed, as opposed to the other tops. (French, Russian: Chapiteau) and obtained a new seating. Miraculously, the show re-opened, initially to large crowds since the destruction of the first tent had attracted great publicity.

But on March 20 in the morning, another disaster befell this decidedly jinxed circus. Apparently, as the Carolis’ riding act was practising in the ring, a fire broke out in the accommodation of George Baker, Togare’s assistant. Panicking, Baker threw out the Primus stove that had started the fire; it was alight, and in seconds, the fire caught the walling of the main tent and quickly destroyed it. Carmo, resting at his home following the trauma of the snow catastrophe, hasted to Birmingham to find the entire outfit destroyed. Although there was no loss of human life, some of the show’s livestock suffered.The valiant Togare did a splendid job getting the lion’s wagons out of a burning tent and putting the badly burnt animals to relative safety. Togare and his assistants worked day and night to save the animals’ lives, putting raw eggs and olive oil on their wounds. The local RSPCA inspector lauded Togare’s gallant action, and he received awards from the Birmingham Chamber of Commerce and from the Society of Our Dumb Friends’ League. The majority of the show’s animals, horses camels and the elephants, were saved too.

Following the Birmingham fire, it was said that after having done all he could, Carmo collapsed and spent some days in bed in a hotel. He had lost a fortune; he was either inadequately insured or, more likely, he had no insurance cover at all. He kept nonetheless the entire company on salary, reorganising the show, and he resumed performances at the West Bromwich Skating Rink by March 27. His liabilities were too great however, and his dream of running a big tenting circus was over. The Great Carmo went back to his magic stage show, Magical Moments.

Carmo’s Colossal Circus

Yet Harry Carmo didn’t completely abandon the circus. In the winter of 1930-31, Carmo’s Colossal Circus was staged at the Hippodrome Theatre in Newcastle-Upon-Tyne as a Christmas and New Year attraction(Russian) A circus act that can occupy up to the entire second half of a circus performance.. The programme listed as Directors of the venture F.A. Lumley (who was from Edinburgh), Chairman, and Harry Carmo and George Sax as Managing Directors, along with J.R. Cookson, R. Rutter, Stanley Pickford and M. Davis. Robert G. Wakeman was General Manager, W.T. Guest, Publicity Manager, and Abe Holloway was Ringmaster and Equestrian Director.

Apparently, Carmo went into some kind of association with Lumley and his partners. The programme still included The Bentos, Togare and his lions, Emmerich Ankner with the horses, and The Hansens’ perch pole act, as well as new attractions such as the Scott Girls, bareback riders; the Five Mounters, equilibrists; Montana Frank and Louie, whip and rope manipulators; The Ladringlos, aerial revolving ladder; the St. Moritz Skaters, a roller-skating duo whose male partner was claimed to have trained Charlie Chaplin in skating; and George Durant’s wire act. (Durant was the brother of Jimmy Nervo, a celebrated comedian who gained fame as part of the comic duo Nervo & Knox—both of whom were later members of the legendary Crazy Gang comedy group.)

Much of the livestock of the Carmo’s Circus was disposed of to help alleviate some of Carmo’s considerable debts, which were to plague him for the rest of his life. His impressive group of lions was split up, and the animals sold off to various zoos and circuses. Togare parted company and went on with his brilliant career, and created a new act with a group of ten lions from Circus Starssburger.Harry Carmo and his new partners had formed a limited company, The Great Carmo Circus Ltd., and during the summer of 1931, they put on Carmo’s Colossal Circus under a tent at South Shore, Blackpool. Hungarian-born Alexander (Sandor) Könyöt, of the famous equestrian family allied to the great Blumenfeld and Goldkette Jewish circus dynasties, was listed in the programme as General Superintendant of the Tents (Tentmaster we would have called him). The son of Harry Carmo’s late wife, Alma, was the Manager (after leaving school, he had been articled to an auctioneer and estate agent in Wakefield); most assumed he was Harry’s son, and he was popularly known in the circus as "Young Harry."

The show, set up on the outskirts of Blackpool, featured Alfred Kaden and his lions; Ernest Milton’s aerial act; Emmerich Ankner with the horse display; the Hugony Sisters, tumblers; Montana Frank and Louie; the Scott Riding Troupe, composed of mother, father, two daughters, and young Arthur Scott; the St. Moritz Skaters; the Ladringlos and their revolving ladder; Speedy Yelding’s comedy wire act; The Yeldings’ riding act; and Harry Coady’s whistling and musical act. Although the programme was undoubtedly an attractive one, it stood no competition to the established and famous Blackpool Tower Circus, and business continued to contribute to Harry’s mounting losses.

Later, in October 1931, Carmo’s Circus was presented for a short season on the stage of the enormous Dominion Theatre in London, under the direction of F.A. Lumley, with Emmerich Ankner as Equestrian Director and R.G. Wakeman as General Manager. The short circus bill featured Mona Connor’s riding act; the De Suter Brothers, musical clowns; Mme Heraldos and her sea lions; high schoolA display of equestrian dressage by a rider mounting a horse and leading it into classic moves and steps. (From the French: Haute école) and of liberty"Liberty act", "Horses at liberty": Unmounted horses presented from the center of the ring by an equestrian directing his charges with his voice, body movements, and signals from a ''chambrière'' (French), or long whip. horses in three displays by Captain Ankner; the Engandine Troupe, springboard acrobats; Duncan’s Collie Dogs; the trio of Hungarian jockeyClassic equestrian act in which the participants ride standing in various attitudes on a galoping horse, perform various jumps while on the horse, and from the ground to the horse, and perform classic horse-vaulting exercises. riders, the Sandor Karoly Brothers; and clowns Toto Brasso and the Zola Brothers. The circus fare was presented three times a day, in conjunction with the theatre’s featured film, Palmy Days, which starred Eddie Cantor (and was presented only twice a day). The horses were stabled in the foyer of this fine theatre, and apparently made a good free display for the public on entering.

In 1932, Harry Carmo experienced more bad luck with his magic show in Paris, the scene of former triumphs; this time, the engagement had been a failure. Back in England, he found that the growing slump in the variety theatre world also affected his business. In 1933, he had to get rid of his assets; the horses had already gone to the Blackpool Tower Circus, where Emmerich Ankner presented them for a couple of seasons. Carmo Manor, his farmhouse in Shirley, was heavily mortgaged and had to be sold.

Harry Carmo And Ray Stott

Rita Rogers, who was still with the Carmo magic show and had become his close companion, suggested he take on a country house near her family’s home in Stanford-Le-Hope, Essex. The new house had grounds enough to take the remaining animals, and outbuildings to store the magic props and scenery. Carmo continued to tour his big magic show with a reduced cast and collection of animals, and he also put on some sideshows at seaside resort towns to make extra money.

An attempt to tour a magic show in a portable theatre with the formerly famous illusionist David Devant as a "sleeping partner" proved another money-loser. In 1935, with the showman Tom Norman, Harry played the big fun fairs (Nottingham, Mitcham, etc.) with a travelling fit-up show, his big illusions reduced to appearing in relatively humble surroundings, with Carmo and his faithful Rita presenting them. With varying success, they also worked in the fast-vanishing variety theatres.The Great Carmo Circus made a final appearance in the summer season of 1937. For this venture, Harry Carmo teamed up with a young journalist and circus lover, Ray Stott. Stott, whose full name was Raymond Toole-Stott (1904-1982), later became famous as the dedicated compiler of the most remarkable circus bibliography, Circus and Allied Arts, which ran to five volumes and began publication in 1958, the final volume being published in 1992—ten years after Stott’s death. Toole-Stott also compiled A Bibliography of English Conjuring, in two volumes in 1976 and 1978, and a bibliography of the works of W. Somerset Maugham. A member of the Magic Circle in England, Ray Stott was also at one time press agent for the Bertram Mills Circus.

In 1936, Stott had taken out a small travelling circus under the title of Ray Stott’s Circus with four partners, W.E. Bousfield, D.W. Warnford-Davis, B. Stewart, and J. Trevor. Douglas Cooke, who came from a famous circus family in England, had been the Equestrian Director, and the modest band of performers included Young Cyclone and Pam, with a rope and whip act; Douglas Cooke with Stott’s "Sumatran liberty"Liberty act", "Horses at liberty": Unmounted horses presented from the center of the ring by an equestrian directing his charges with his voice, body movements, and signals from a ''chambrière'' (French), or long whip. horses" and a pony; clowns Sam Andy, Bobino and Hendrik; the Four Wonder Wheelers in a cycling act; Leslie d’Aquilla with a troupe of grey horses, and a dog and pony act; The Atlantics on a swinging bamboo pole; bucking zebra "Nina"; and the Seven Fredysons in a springboard act. Lulu Craston, the British lady clown (and daughter of the famous clown Joe Craston), was also with the show. The most remarkable act in this programme must have been the famous Hollywood Chimpanzees, Max, Moritz and Akka, presented by Ruben Castang, a celebrated animal trainer from the Hagenbeck school: The chimps had acquired fame appearing in American movies for eight years, and Castang was known in Hollywood as "The Wild Animal Man."

The new Stott-Carmo combine made its debut at Maidstone, Kent, in July 1937. It was described as an unpresumptuous but well produced circus, which toured small towns in Devon and Cornwall, and which, again, made little money. Ellis Cooke was the Ringmaster and also presented a dog and pony act, and the show boasted "A Noah’s Ark of Animals"—something quite modest, no doubt. In the programme were Irene, wire act; Speedy Yelding, clown and comedy wirewalker; Isabelle, ballerina on horseback; Eno & Arno, comedy act; Vic Lane & Partner, aerial act; “Reggie, the Intelligent Horse”; René, voltige rider; Tommy Bartlett with "Rosie, the Wonder Elephant"; The Starlights, Wild West act; and the clowns Tony Goodall and George Freeman.

Most notable was the inclusion of The Great Carmo himself, the first and only time the great magician appeared in a circus bearing his name. In the first of four appearances, he presented The Glass Trunk, The Illusive Cannonball, and The Crystal Treasure Chest; later he brought "A mystifying exhibition of Chinese Magic", and he returned with Carmo’s Cocktail Bar, with his famous Magic Kettle illusion. In the final part of the show, he presented his celebrated disappearing lion illusion.

Publicity for that final season still advertised the famous people who had patronised The Great Carmo Circus in its more glorious days; they included Lord and Lady Birkenhead, Dame Laura Knight, Lady Cunard, Sir Thomas Beecham, Lady Diana Duff Cooper, Sir Philip Sassoon, Lady Eleanor Smith, Lady Pamela Smith, and Lady Duff Gordon.

The Final Years

By the time of his last circus involvement, Carmo had moved home again, to Pebmarsh in Essex. As she had done since Alma Cameron’s death, Rita Rogers’ mother kept house.

In 1938, Carmo had a small show at the Glasgow Empire Exhibition, and in 1939, he was back working the fairgrounds, for Pat Collins at Great Yarmouth. When the Second World War came, Carmo retired to Pebmarsh, but in 1941, he and Rita joined ENSA (Entertainment National Service Association), the forces’ entertainment organisation, with a magic revue titled Hey Preston, built around Carmo’s talents. The following year, he toured with a variety show visiting the forces’ camps, aerodromes and bases, in which he was also the Unit Manager.

Rita Rogers remained faithful to Harry Carmo and his exploits all those years, and it is believed that the dying Alma had exacted a promise from him never to remarry. But Harry and Rita were eventually married on October 20, 1943 in Fort William. They were working in Ireland when Harry surprised Rita outside a jeweller’s shop by proposing; they had worked together for some twenty years.

Less than a year after their belated marriage, Harry Carmo suffered a cerebral haemorrhage and was rushed to a hospital, where he died on August 1, 1944. He was buried in the churchyard at Pebmarsh; Rita, her mother, and her younger brother Ken, who had latterly worked backstage with the magic show and the circus, were the only mourners.

With little money left, but with a determination to continue the Carmo’s legacy, Rita sorted out the smaller magic tricks he had performed in order to create a magic act for herself. She worked with ENSA until the end of the war, gaining much needed confidence and experience. Then she went out with her magic act as La Petite Carmo, working variety shows with good success until 1951; most people assumed she was Carmo’s daughter, and even granddaughter. She left the stage when her brother became sick, and settled in a village near Cambridge. Ken died in 1972, and Rita later on, in the 1980s, thus ending the saga of The Great Carmo.

In June 2000, members of the Magic Circle found the churchyard of Pebmarsh and the unmarked grave in which Harry Cameron had lain for fifty-six years. They had raised money to erect a stone in memory of this great character from the world of entertainment. They were directed to the spot where Carmo rested by an old lady who had dwelt in the shadow of the churchyard since her own childhood. She could remember Carmo’s lion, Roger, roaring at night in the still air, and added: "There are nights when I fancy the lion still roars!"

Suggested Reading

- Val Andrews, The Great Carmo, The Colossus of Mystery (Essex, Arcady Press, 2001)

- Cyril Bertram Mills, Bertram Mills Circus — Its Story (London, Hutchinson, 1967; paperback reprint published by Ashgrove Press, Bath, in 1983) — ISBN 0-906798-22-1

- David Jamieson, Bertram Mills — The Circus That Travelled By Train (Little Hormead, Aardvark Publishing, 1998) — ISBN 1-872904-11-4