Arturo Castilla

From Circopedia

Circus Director and Impresario

By Raffaele de Ritis

In post-WWII Europe, the Spanish impresario Arturo Castilla (1916-1996) was one of the most active and successful advocates of the circus’s integration into the modern entertainment industry. In this, he followed a few other visionary mavericks such as Jérôme Medrano and Bertram Mills, and preceded Jean Richard, Bernhard Paul, Pierrot Bidon, and others. Castilla’s major achievements were the introduction of theatrical aesthetics into the traveling circus performance, a modern approach to public relations and marketing, his foresight of the emerging sport arenas’ potential, and the pioneering of trans-national synergies between major European circuses.

With his partner and brother-in-law, Manuel Feijóo (1897-1969), Castilla produced circus shows in Spain and abroad, managed the legendary Circo Price building in Madrid, organized circus festivals and congresses, and presented foreign circus companies in Spain. These activities, added to his remarkable talent at establishing connections with the media and the political establishment of Francisco Franco’s Spain, helped him build a conservative aesthetic of the circus as a celebration of diverse "national" identities, and as a tool for "cultural" propagandistic exchanges, which would be widely emulated.

From Los Hermanos Cape To Feijóo Y Castilla

Arturo Castilla Rodriguez was born in Bilbao, Spain, on October 22, 1916. His father, Raimundo, was a journalist. Arturo was thirteen years old, in 1929, when Raimundo took him to see the colossal German circus Krone, which was visiting Bilbao. This visit triggered Arturo’s fascination with the circus world. Arturo Castilla eventually studied fine arts at the Escuela de Artes y Oficios de Atxuri, in Bilbao, and joined at the same time an amateur circus clubA juggling pin.. Circus eventually took precedence over painting, and Arturo formed a clown act with three old friends of his: Carlos Izquierdo, Pedro Talavera, and Esteban Galdós.Together, as the Hermanos Cape, they went on to perform for various Spanish circuses. (Clowns have always been very popular in Spain—a country that has produced over several generations a remarkable number of outstanding clown stars.) In 1940, Arturo and the Hermanos Cape were working at Circo Feijóo, a medium-size traveling circus created in 1885, which had been known for decades as a "clown heaven," and whose ring had been graced by such illustrious funny men as Rico & Alex, the Albano Brothers, Pompoff y Thedy, the Andreu-Rivels, and even, in the nineteenth century, Tony Grice—the clown who tutored the legendary augusteIn a classic European clown team, the comic, red-nosed character, as opposed to the elegant, whiteface Clown. Chocolat. The Hermanos Cape spent six seasons with Circo Feijóo, during which Arturo Castilla became good friends with Manuel Feijóo-Salas, the owner's son.

Arturo and Manuel eventually married two sisters, Pilar and Mercedes Sánchez Rexach, the daughters of Don Mariano Sánchez Rexach (1885-1937), one of the most prominent circus producers in Madrid between the two World Wars. In 1919, Sánchez Rexach had built a permanent wooden structure on the Plaza del Carmen, the Circo Americano—whose name was inspired by the recent European fame of Barnum & Bailey Circus and the Buffalo Bill’s Wild West, both of which, however, never visited Madrid: The Spanish-American war over Cuba had occurred in 1898, and since the American entertainment behemoths visited Europe at the turn of the twentieth century, they certainly didn’t wish to tempt fate in Spain. Circo Americano was demolished in 1930, when Sánchez Rechax took over the management of Leonard Parish’s more prestigious (and more profitable) Circo de Parish building, on the Plaza del Rey in Madrid, to which he gave back its original name, Circo Price.

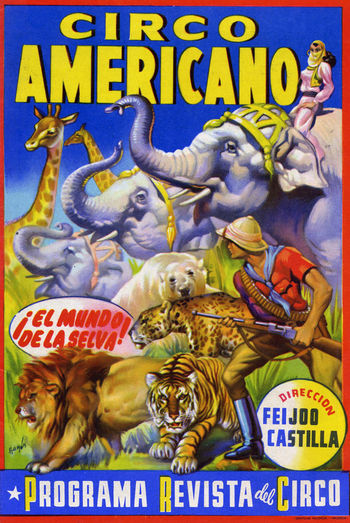

In 1946, Arturo Castilla and Manuel Feijóo launched a traveling circus of their own also named Circo Americano—a title that was not only a tribute to their father-in-law, but also an ideal choice in a post-war ultra-conservative Spain exalting the values of the western civilization against the threat of eastern Communism. They purchased from the Alvarez circus family a second-hand, one-ring traveling semi-construction(French) A temporary circus building, originally made of wood and canvas, and later, of steel elements supporting a canvas top and wooden wall. Also known as a "semi-construction." with a canvas top and a wooden sidewallThe canvas wall at the periphery of a circus tent.. With such popular attractions as the hypnotist Fassman and the star-clown Ramper, they were able to hold a town’s attention for weeks.

The opportunity to create a truly "American-style" circus came in 1951, when Castilla booked Edward "Joe" Gray, a former captain of the Canadian Mounties who, in the late 1940s, went into show business as a Buffalo Bill impersonator, performing a trickAny specific exercise in a circus act.-roping and knife-throwing act in various European circuses. Castilla created around his new star an impressive advertising campaign replete with spectacular street parades, and featured his Buffalo-Bill look-alike on horseback, surrounded by "Indians" and cowboys in lavish production tableaux.

Circo Americano

In the 1950s, Circo Americano’s big topThe circus tent. America: The main tent of a traveling circus, where the show is performed, as opposed to the other tops. (French, Russian: Chapiteau), trailers and overall decoration began to adopt a stars-and-stripes, red-white-and-blue theme that will remain its trademark look. Circo Americano pioneered an innovative way, at the time, to present a traveling circus show: Feijóo and Castilla were not only showing great circus acts, they introduced the Spanish circus world to the concept of theatrical productions, inspired by the popular Spanish tradition of the traveling companias de revista (revue companies)—some of which performing under canvas—and the lavish staging of the zarzuela, a Spanish form of operetta of which Castilla was a big fan.Circo Americano was one of the first circuses in Europe (beside the Soviet circus) to create specific costumes and musical arrangements for both production numbers and contracted acts. The brass band of Emilio Estevéz, fifteen member-strong, joined the circus and gave music concerts in resplendent hussar uniforms in each town. The operetta fan and former art student Arturo Castilla gave a special attention to scenery, costumes, personnel uniforms, and musical direction. The meticulous staging of his productions was built around a system of changing curtains and backdrops, and a revolving stage platform.

New productions were created year after year: a pantomimeA circus play, not necessarily mute, with a dramatic story-line (a regular feature in 18th and 19th century circus performances). named Pompei in 1952 incorporated several circus acts between production numbers and water effects; Cossacks of the Tsar was staged in a similar vein; 1001 Nights was built around the famous illusionist Chefalo; The New World was a space-age fantasy; there were also Kongo; The Wonders of the World; and another Wild-West spectacular, Rodeo U.S.A., which featured the trickAny specific exercise in a circus act.-roper Lance King, David Rosaire and his comedy horse, and the troupe of Cossack riders, The Bratuchins. The Circo Americano’s recipe was taking shape: world-class acts and animal galore incorporated in a fully staged and themed production, replete with parades, floats, scenery and original musical arrangements. The very influential Spanish circus critic, Sebastian Gasch, wrote in 1952: "Messieurs Castilla and Feijóo have often been accused of modernizing the circus by giving it an air of revue, or by dressing their shows like an operetta (…); I think those gentlemen not only don’t distance themselves from the tradition, but they keep it alive by giving back to the circus its original pomp and its initial power…"

Instead of traditional circus ringmasters, Castilla booked movie- or radio-trained actors, such as Alicia Altabella or Roland Sollath, or revue stars such as Eva Miller. Then, the acts: A quick glimpse trough the programs of the 1950s reveals a constellation of great equestrians (Carré, Gindl, Mullens, Picard, Rosaire…), star wild-animal trainers (Firmin Bouglione, Ivanoff and his pupil, Pablo Noel…), great acrobats (Morways, Mascotts, Atilina Segura…), aerial acts (Mara, Croneras…), clowns and comedy acts (Joy Kay & Co., The Tonettis, Eduardini, Hugh Forgie…), and much more. Castilla’s magic touch could turn the tiger trainer Emilien Beautour into Taras Bulba, or Pinito del Oro and Tony Steele into media stars.

In 1958, Circo Americano’s big topThe circus tent. America: The main tent of a traveling circus, where the show is performed, as opposed to the other tops. (French, Russian: Chapiteau) was enlarged to a six-pole tent; the single ring was now in the center of a vast hippodrome track used for parades, and the artists’ entrance, veiled with a lavishly decorated curtain, ran along the back of the hippodrome track. The entire Circo Americano setting was conceived as an attractive and comfortable place for the audience, long before Circus Roncalli, Circo Tihany or Cirque du Soleil, and had a consistent themed decoration. Arturo Castilla had a very simple, yet powerful secret, which he applied to his circus: his attention to detail.

Posters and general advertising were designed by well-known advertising artists, who borrowed part of their imagery from classic American circus posters (with the notable use of the attractive faces of Ringling’s iconic clowns Paul Jung and Lou Jacobs)—developing a style that would deeply influence European circus advertising in the following decades.

The Circo Americano’s annual tour usually began in April at the Easter fair in Madrid, continued in Lisbon (Portugal), visited the main Spanish cities during the summer, and ended in Barcelona in November. By 1956, Circo Americano had become so popular that Feijóo and Castilla launched three additional touring units—actually renting their label to less important circuses, whose shows were built around Circo Americano’s productions from previous seasons, using the original costumes, scenery, themes, and overall production elements.

Nationalistic Strategies

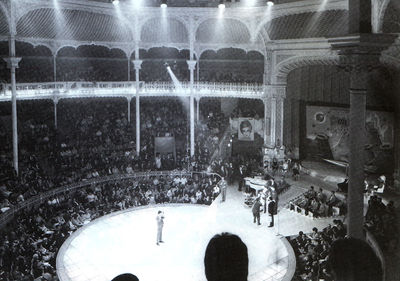

Meanwhile, Manuel Feijóo and Arturo Castilla expanded the range of their interests: in 1960, succeeding the great Spanish impresario Juan Carcellé, they took over the management of Circo Price in Madrid. They renovated it to its full glory, and started booking for its shows the greatest circus talents available. In 1962, Arturo Castilla made a deal with Hollywood producer Samuel Bronston, who rented Circo Price for the filming of a sequence of Henry Hathaway’s movie, Circus World, starring John Wayne, Rita Hayworth and Claudia Cardinale. The sequence featured the Swiss clown Pio Nock walking the high wireA tight, heavy metallic cable placed high above the ground, on which wire walkers do crossings and various acrobatic exercises. Not to be confused with a tight wire. above the lions of Henri Dantès.

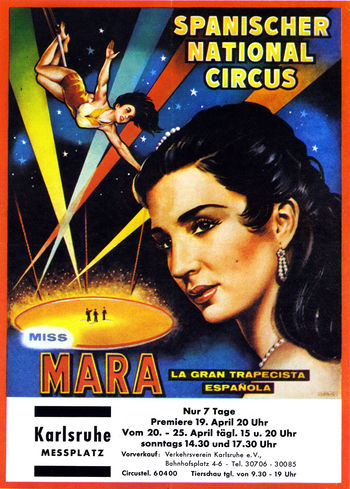

Then, Arturo Castilla began to establish himself as a major player in the nationalistic cultural propaganda of Franco’s dictatorship. In 1961 he sent a Spanish circus program to the Amsterdam RAI arena in Holland, which included such stars as the famous clown quartet Rudi-Llata, the aerialistAny acrobat working above the ring on an aerial equipment such as trapeze, Roman Rings, Spanish web, etc. Miss Mara, and Pablo Noel and his lions. Guest Artist on her own territory, the great Dutch equestrienneA female equestrian, or horse trainer, horse presenter, or acrobat on horseback. and circus director Elly Strassburger presented her horses. Unfortunately she soon discovered that she had put herself in a rather humiliating position.

Elly’s family (and herself) had reigned over Circus Carré in Amsterdam for ten years during the winter season, and ran Circus Strassburger in Scheveningen during the summer. The Strassburgers were a prominent Jewish circus family, who had owned one of Germany’s most important circuses before WWII; in 1938, as anti-Semitism reached its peak in Germany, they were forced to sell their circus and take refuge in Holland. After the War, Circus Strassburger was revived as Holland’s premier circus, and once again Strassburger became one of the most respected circus names in Europe. Nonetheless, the Spanish press wrote derogatory remarks on Elly Strassburger’s presence in the show, comparing her unfavorably to the Spanish performers.

In 1962, Circo Americano started touring Germany under the title Spanischer National Circus, in association with the German Circus Williams. Beside Circus Williams’s animals and horses, presented by its in-house trainer, Gunther Gebel-Williams, along with his wife, Jeanette Williams, the show had a Spanish cast and theme. At the time, Germany and Spain had established important political and commercial relations, which led a great number of Spanish workers to immigrate to Germany; the tour was punctuated by diplomatic visits of political guests, the importance of which was duly amplified in the Spanish press.The German tour began on March 23, 1962. To keep their footprint on the Spanish market, Feijóo and Castilla toured the country with a relatively smaller show, Circo Monumental. Of course, they still ran the Circo Price building, which was renamed Price-Hall and offered now a multidisciplinary calendar. The Spanischer National Circus toured in Germany until 1966 and became one of the most successful circuses in Europe. It also helped establish Gunther Gebel-Williams as a major circus personality in Europe.

In 1963, the news spread across Europe that John Ringling North was sending a touring unit of Ringling Bros and Barnum & Bailey Circus, The Greatest Show On Earth, to Europe. Seeing an obvious and dangerous competition for his Circo Americano title, Arturo Castilla signed a contract with Enis Togni, whose huge Circo Heros was Italy’s (and one of Europe’s) largest circus. Since the Ringling show was scheduled to play sport arenas, Castilla and Togni booked a winter tour of Circo Americano in major Italian sport arenas (the Ringling show was unlikely to visit Fascist Spain)—venues that were rather new to European circus organizations.

By an uncanny coincidence, Circo Americano’s opening day in Turin was slatted on Friday, Novenber 22, 1963—the day John F. Kennedy was assassinated. The opening was postponed for a day, bringing emotional extra publicity to the event: It was after all, the inaugural visit of Circo Americano (the "American Circus") to Italy, which had been heralded with much fanfare, the Castilla way. The fact that it was in actuality a Spanish-Italian-German show with no Americans in the cast or the management didn’t matter, since nobody was meant to know it.

The combination of Togni’s and Williams’s talented troupes and vast animal collections with Castilla’s flair for production and marketing generated a show that was far better than what Ringling had planned for its European tour. (Ringling’s tour had been actually badly planned, with a rather poor appreciation of Europe’s artistic standards as well as of its circus market—to North’s utter dismay and eventual anger.) The Circo Americano’s star-studded show ended with a spectacular display of twenty-six elephants working together in the vast hippodrome under the guidance of Erwin Bauer, Henry Strassburger, Bruno Togni and Gunther Gebel-Williams—an image against which Ringling’s hastily gathered herd of eleven elephants performing in three separate groups couldn’t compete.

Ringling never went so far as Italy: After a few disappointing dates in France and Holland culminating with a rather unsuccessful run in Paris, The Greatest Show On Earth packed its bags and returned to the United States. On the other hand, the very successful Circo Americano's Italian project was expanded to other cities the following winters. During the summer season, Castilla toured Circo Monumental in Spain, while Williams toured the Spanischer National Circus in Germany and the Tognis toured with their Circo Heros retitled Italian National Circus in both Germany and Holland. Then they all combined their efforts in Italy during the winter season with two units playing simultaneously, Circo di Berlino and Circo di Madrid, both presenting Castilla productions. This nationalistic vein was also carried to Circo Price in Madrid, which hosted foreign "national" companies such as the Cirque de Paris (actually the French Cirque Rancy), the Circo Nacional de Budapest (the Hungarian State Circus), etc.

Farewell To Circo Price: The Final Years

Germany’s Circus Williams closed in 1968, as Gunther Gebel-Williams sailed to the United States with his menagerie to star with Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey. Feijóo y Castilla and Togni combined their companies for simultaneous tenting tours of Circo Americano in Spain and Italy, with a new three-ring format. The Castilla team devised a new spectacle, The Cristopher Columbus Parade, which made good use of Togni’s aerial ballet, horses and elephants.

In November 1968, Arturo Castilla organized the World Circus Congress, which was held under Circo Americano’s big topThe circus tent. America: The main tent of a traveling circus, where the show is performed, as opposed to the other tops. (French, Russian: Chapiteau) in Barcelona. It was an international gathering of circus enthusiasts, journalists and historians, who discussed the situation of the circus and its future. Pablo Picasso illustrated the cover of the printed program, and Salvador Dalí, among others, attended the closing gala performance. The event had an enormous success—and was a personal triumph for Arturo Castilla.

Manuel Feijóo, Castilla’s long-time partner and brother-in-law, passed away in 1969. He had been spared the demise of their crown jewel, Circo Price: In 1970, real estate investors forced Castilla to vacate Madrid’s legendary circus building. Trapeze star Pinito del Oro said, “If Price has to close, I’ll end my career with it and put my bar away forever.” On April 12, 1970, Arturo Castilla produced Circo Price’s last show, which featured the great clown Charlie Rivel, and Pinito del Oro’s farewell performances. A few months later, the building was torn down. In 1971 Castilla launched a new Gran Circo Price touring under the big topThe circus tent. America: The main tent of a traveling circus, where the show is performed, as opposed to the other tops. (French, Russian: Chapiteau); it lasted until 1976.To counterbalance the loss of his winter home, Castilla revived the Festival Mundial del Circo in the winter of 1970, which he presented in sport arenas. The formula had been originated by the impresario Juan Carcellé, who had produced the Festival from 1956 to 1962. It was a traditional circus show presented as a circus competition; at the end of the run, the winning act received the Oscar Mundial del Circo. The Castilla version lasted until 1980: By then, the advent of true circus festivals such as the International Circus Festival of Monte Carlo and the Festival Mondial du Cirque de Demain in Paris had rendered Castilla’s formula somewhat obsolete.

Castilla kept working on other projects: He wrote and produced operettas, organized hugely successful Spanish tours of the Moscow Circus, the Red Army Choir, and Andalusian equestrian shows. He conceived a produced a new lavish spectacular for the Togni unit of Circo Americano for its 1972-74 tour of Spain and Italy, with a finale pantomimeA circus play, not necessarily mute, with a dramatic story-line (a regular feature in 18th and 19th century circus performances). that would become a classic, From The Far West To Space. His association with Circo Americano eventually ended in 1976, when name and concept passed definitely into Togni’s hands. (Since the 1990s, another circus, managed by the Faggionis, an Italian circus family, has used the title Circo Americano in Spain.)

Arturo continued working on a variety of projects: The management of foreign circuses visiting Spain, the direction of the Teatro Monumental in Madrid, the casting of the Spanish productions of the musicals Barnum and Evita, and the production of flamenco choreographer Antonio Gades’s legendary Carmen. In May 1988 Catilla organized the World Congress of Circus Fans, to which the King of Spain gave his patronage, and he spent his final years fighting for his greatest dream: An official legal recognition of the circus in Spain, and a Spanish circus school. He also strongly supported a project for the rebuilding of Circo Price in Madrid, for which purpose he created a dedicated association, Pro Cultura SL, which lobbied intellectuals and various personalities for the cause.

Arturo Castilla died on November 12, 1996. He was eighty years old. He had been Spain’s most ardent circus advocate, and although he never saw his dream of a new Circo Price come to life, his fight had been nonetheless worth it: A new, state-of-the-art Teatro Circo Price was built in the center of Madrid, on Ronda Atocha, one hundred and forty-one years after the opening of the original Circo de Price. It was inaugurated in March 2007.

Suggested reading

- Arturo Castilla, La Otra Cara del Circo (Madrid, Albia – Grupo Espasa, 1986) — ISBN 84-7436-601-1

- Jordi Jané, Joan M. Minguet, Sebastià Gasch, El Gust Pel Circ – Antologia de textos (Barcelona, Máedol, 1997) — ISBN 84-89936-12-9

- Juan Felipe Higuera Guimerà, El circo en España y el Circo Price de Madrid (Madrid, Editorial J. García, 1998) — ISBN 84-95144-00-X

- Carlos Bacigalupe, Arturo Castilla, que soñaba circos (Bilbao, Muelle de Uribitarte Editores, 2007) — ISBN 8493477494

- Raúl Egyuizábal, Historias del Circo Price y otros circos de Madrid (Madrid, Ediciones La Libreria, 2007) — ISBN 978-84-96470-95-8